For years the drilling industry has steadfastly insisted that there has never been a proven case in which fracking has led to contamination of drinking water.

Now Environmental Working Group, an advocacy organization engaged in the debate over the safety of fracking, has unearthed a 24-year-old case study by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that unequivocally says such contamination has occurred. The New York Times reported on EWG's year-long research effort and the EPA's paper Wednesday.

The 1987 EPA Report, which describes a dark, mysterious gel found in a water well in Jackson County, W.Va., states that gels were also used to hydraulically fracture a nearby natural gas well and that “the residual fracturing fluid migrated into (the resident’s) water well.”

The circumstances of this particular well are not unique. There are several other cases across the country where evidence suggests similar contamination has occurred and many more where the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing have contaminated water supplies on the surface. ProPublica has written about many of them in the course of a three-year investigation into the safety of drilling for natural gas.

But the language found in the EPA report made public Wednesday is the strongest articulation yet by federal officials that there is a direct causal connection between man-made fissures thousands of feet underground and contaminants found in well water gone bad. The explanation, presented in the EPA’s own words, stands in stark contrast to recent statements made by EPA officials that they could not document a proven case of contamination and a 2004 EPA report that concluded that fracturing was safe.

“This is our leading regulatory agency coming to the conclusion that hydraulic fracturing can and did contaminate underground sources of drinking water, which contradicts what industry has been saying for years,” said Dusty Horwitt, EWG’s senior counsel and the lead researcher on the report.

A spokesperson for the EPA would not directly address the apparent contradiction but said in an email that the agency is now reviewing the 1987 report and that “the agency has identified several circumstances where contamination of wells is alleged to have occurred and is reviewing those cases in depth.”

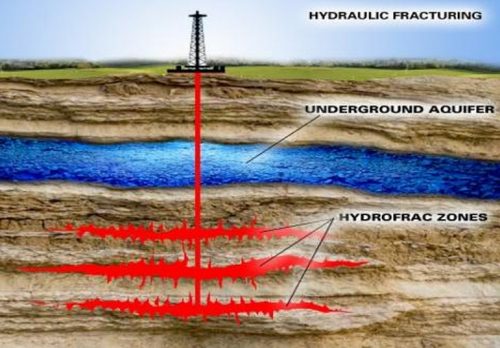

The contamination debate has intensified as tens of thousands more wells are being drilled in newly discovered shale gas deposits across the country. The EPA and some scientists have long warned that when rock is hydraulically fractured, there is an increased risk of contaminants traveling through underground cracks until they reach drinking water. Many geologists have countered, however, that migration over thousands of feet is virtually impossible.

Although the EPA, along with West Virginia officials, concluded that fracturing caused the contamination studied in its 1987 paper, the documents from the agency’s investigation contain many of the same ambiguities that have allowed the industry to continue to deny a link between water contamination and fracking. In the West Virginia case, for example, officials did not collect chemical samples of the drilling fluids used for fracturing and therefore could not test the contaminated water for the presence of those chemicals. Officials noted that they did not have sufficient time to fully investigate that case.

“No one at the time tested the gel to see its chemical composition so you can’t know for sure where it came from,” said Horwitt.

Such scientific stumbling blocks have prevented regulators from reaching more definitive conclusions in several cases that have roused concern about fracturing.

In 2006 — according to a ProPublica report — a residential drinking water well in Garfield County, Colo., spewed gas and polluted water into the air after a nearby gas well was hydraulically fractured. Tests detected a chemical called 2-butoxyethanol (2-BE), commonly used in hydraulic fracturing, in the drinking water well. The EPA never studied the case, and Colorado officials did not pursue an in-depth investigation before the gas company reached a multimillion-dollar settlement with the homeowner that included nondisclosure agreements.

In 2009, when the EPA began investigating a pattern of residential well water contamination in Pavillion, Wyo., the agency identified a close chemical relative of the 2-BE compound identified in the Colorado case. It is also likely that 2-BE was used in fracking in Pavillion, but the EPA’s investigation is ongoing, and the agency has not decided whether fracking was the cause.

In many of the contamination cases ProPublica has documented across the nation — including dozens in which methane contamination reached water wells and at least a thousand in which water was otherwise contaminated in fracking areas — the drilling industry and environment officials have blamed well construction, rather than the fracking process. The industry has used this finding to argue that better well construction is enough to make drilling safer and to argue against federal regulation of fracking.

In the case studied in the EPA’s 1987 report, Horwitt said, nothing in the record indicates that there was a leak or other problem in the well casing, leaving an abandoned well as the likely pathway for contaminants to migrate into drinking water. There are millions of such abandoned wells around the country.

The industry group Energy In Depth disputes the clear-cut language of the EPA’s 1987 report and arguing that state regulators were far less certain about the cause of contamination in West Virginia than the EPA’s summary report conveyed. “It says an awful lot about fracturing’s record of safety that the best these guys could come up with after studying the issue for an entire year is a single, disputed case from 30 years ago that state regulators at the time believe had nothing to do with fracturing,” said Lee Fuller, vice president of government relations for the Independent Petroleum Association of America, in a statement published on EID’s website. “Three decades later, the technology today is better than it’s ever been, the regulations are broader and more stringent, and the imperative of getting this right, so that we can take full advantage of the historic opportunities made possible by shale, has never been more apparent.”

Last year the EPA launched its first comprehensive study into the effects of fracking on drinking water. Its findings are due out in late 2012.

ProPublica’s Nick Kusnetz contributed to this report.