Washington, D.C. – Risk analysts have concluded that the disposal of contaminated wastewater from hydraulic fracturing (or “frackingâ€) wells producing natural gas in the intensively developed Marcellus Shale region poses a substantial potential risk of river and other water pollution.

That conclusion, the analysts say, calls for regulators and others to consider additional mandatory steps to reduce the potential of drinking water contamination from salts and naturally occurring radioactive materials, such as uranium, radium and radon from the rapidly expanding fracking industry. The new findings and recommendations come amid significant controversy over the benefits and environmental risks associated with fracking. The practice, which involves pumping fluids underground into shale formations to release pockets of natural gas that are then pumped to the surface, creates jobs and promotes energy independence but also produces a substantial amount of wastewater.

In light of their review of multiple possible water pollution scenarios, the authors say future research should focus mainly on wastewater disposal. “Even in a best case scenario, an individual well would potentially release at least 200 m3 of contaminated fluids,” according to doctoral student Daniel Rozell, P.E., and Dr. Sheldon Reaven, Associate Professor and Director of Energy and Environmental Systems Concentration in the Department of Technology and Society, Stony Brook University. The scientists present their findings in a paper titled “Water Pollution Risk Associated with Natural Gas Extraction from the Marcellus Shale,” which appears in the August 2012 issue of the journal Risk Analysis, published by the Society for Risk Analysis.

|

|

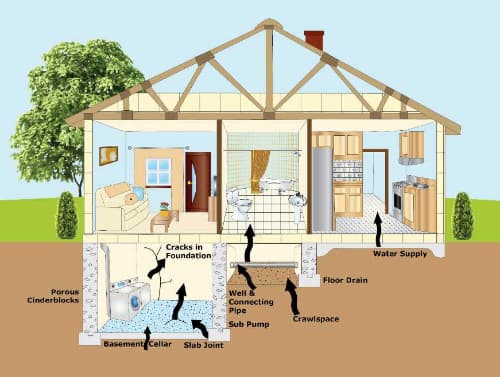

Disposal of the large amounts of fracking well wastewater that is expected to be generated in the Marcellus Shale region—which covers approximately 124,000 square kilometers from New York to West Virginia—presents risks from salts and radioactive materials that are “several orders of magnitude larger” than for other potential water pollution pathways examined in the new study. Other water pollution pathways studied include: a tanker truck spilling its contents while transporting fluids used in the drilling process going to or from a well site; a well casing failing and leaking fluids to groundwater; fracturing fluids traveling through underground fractures into drinking water; and drilling site spills at the surface caused by improper handling of fluids or leaks from storage tanks and retention ponds. The disposal of used hydraulic fracturing fluids through industrial wastewater treatment facilities can lead to elevated pollution levels in rivers and streams because many treatment facilities “are not designed to handle hydraulic fracturing wastewater containing high concentrations of salts or radioactivity two or three orders of magnitude in excess of federal drinking water standards,” according to the researchers. The wastewater disposal risks dwarf the other water risks, although the authors say “a rare, but serious retention pond failure could generate a very large contaminated water discharge to local waters.”

In trying to understand the likelihood and consequences of water contamination in the Marcellus Shale region from fracking operations, Rozell and Reavan use an analytical approach called “probability bounds analysis” that is suitable “when data are sparse and parameters highly uncertain.” The analysis delineates best case/worse case scenarios that risk managers can use “to determine if a desirable or undesirable outcome resulting from a decision is even possible,” and to assess “whether the current state of knowledge is appropriate for making a decision,” according to the authors.

The authors note that “any drilling or fracturing fluid is suspect for the purposes of this study” because “even a benign hydraulic fracturing fluid is contaminated once it comes into contact with the Marcellus Shale.” Sodium, chloride, bromide, arsenic, barium and naturally occurring radioactive materials are the kinds of contaminants that occur in fracking well wastewater.

|

|

If only 10 percent of the Marcellus Shale region was developed, that could equate to 40,000 wells. Under the best-case median risk calculation that Rozell and Reavan developed, the volume of contaminated wastewater “would equate to several hours flow of the Hudson River or a few thousand Olympic-sized swimming pools.” That represents a “potential substantial risk” that suggests additional steps should be taken to lower the potential for contaminated fracking fluid release, the authors say. Specifically, they suggest that “regulators should explore the option of mandating alternative fracturing procedures and methods to reduce the wastewater usage and contamination from shale gas extraction in the Marcellus Shale.” These would include various alternatives such as nitrogen-based or liquefied petroleum gas fracturing methods that would substantially reduce the amount of wastewater generated.

Source: Society for Risk Analysis (SRA)