Native communities are resilient, organized, and rising up.

Wampanoag. Massachusett. Nipmuc. Mohegan. Pequot. Narragansett. Passamaquoddy. Miꞌkmaq. These are just some of the indigenous nations of the land now called New England, the home of that original Thanksgiving dinner that occurred 400 years ago, in the fall of 1621. The myth of that shared meal has evolved over the centuries, depicting friendship and cooperation between the English settlers in Plymouth, Massachusetts and the Wampanoag people who had been there for at least 10,000 years. While that gathering was peaceful, it was at best a token respite from the European settler colonists’ genocide against native peoples that was already well underway. While families gathered across the country for this year’s Thanksgiving celebration, frontline indigenous communities that have survived centuries of violence, displacement and systemic racism remain in resistance, defending land, water and their very existence.

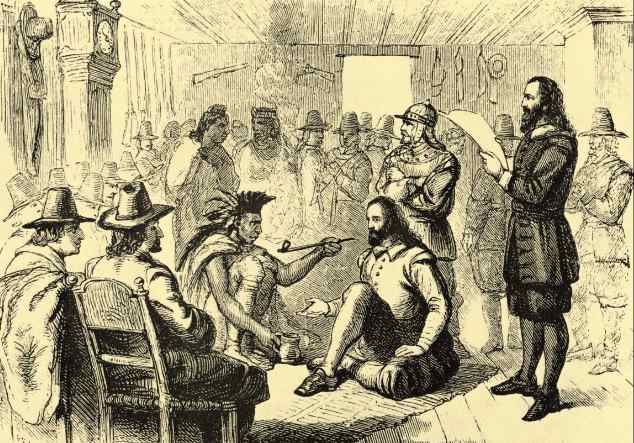

Those 100 or so early settlers, popularly referred to as “Pilgrims,” arrived on Wampanoag territory in 1620. After the first winter, wracked by disease and hunger, their number had dwindled to 54. Indigenous people came to their aid, teaching them how to cultivate local crops. By harvest time, the settlers managed to store enough food to survive the coming winter, so they organized a celebratory feast. The Wampanoag people had just suffered a multi-year plague that had decimated native populations across the region, and, historians believe, sought a strategic partnership with the settlers. English King James I was encouraging colonization, and even touted the benefits of the deadly contagion, calling it a “wonderful plague,” in a 1620 proclamation, leading “to the utter Destruction, Devastacion, and Depopulation of that whole Territorye.”

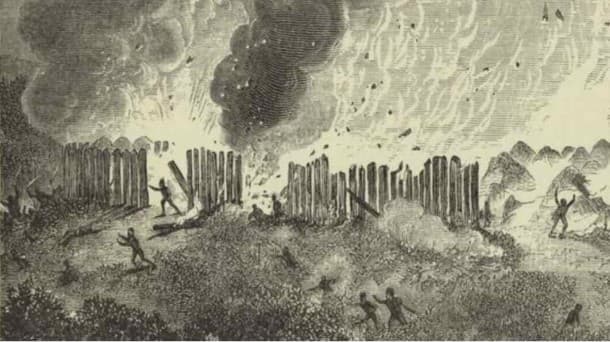

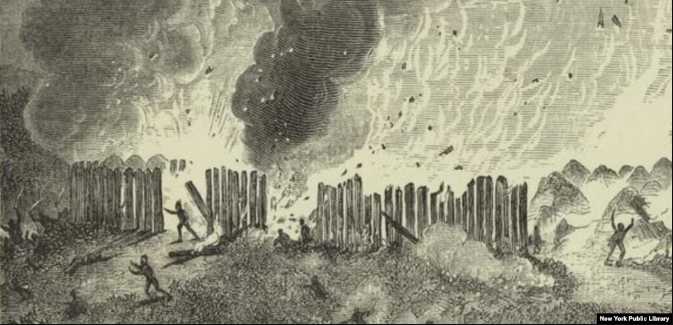

That was the era that the late historian Bernard Bailyn, who died last year at the age of 97, described as “The Barbarous Years,” as the “Pilgrims” mounted increasingly savage massacres and military campaigns against those natives whose land they wanted. Later leaders would couch the ongoing genocide in more diplomatic language with colonial initiatives like “Manifest Destiny,” and the 1934 “Indian Reorganization Act,” that cemented the modern system of impoverished and neglected reservations.[content id=”79272″]

The Declaration of Independence lists among its grievances against King George III his encouragement of attacks against the colonists by “merciless Indian Savages.” From 1777 through 1868, the United States signed at least 368 treaties with native nations — and violated every one. Canada’s track record is comparable. Indigenous people have never stopped demanding that these treaties, and their national sovereignty, be honored.

In the fall of 1969, a group of Native American activists occupied the abandoned federal prison on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, issuing a sarcastic manifesto demanding Alcatraz become a reservation as it bore all the hallmarks of one: it was isolated, had no running water, sanitation, access to education, healthcare or employment, and its occupants would be treated like prisoners. The 19-month occupation involved thousands of people and inspired indigenous people across North America to demand justice. The American Indian Movement was founded, leading to the 1973 activist occupation of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, galvanizing international solidarity for indigenous rights.

In 2016, indigenous resistance catapulted into global headlines as Lakota and Dakota people opposing construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline established resistance camps at Standing Rock. After DAPL’s owner, Energy Transfer Partners, sicced dogs and beat native water defenders, the camps swelled to over 10,000 people, with over 200 indigenous nations and tribes represented. The pipeline was eventually built, but a new era of native resistance had emerged.

Now, pipelines are being constructed to move the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel, tar sands petroleum in western Canada. Indigenous-led resistance to Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline in northern Minnesota has been waged for years now. Anishinaabe leader Winona LaDuke has been on the frontlines there. She criticized President Joe Biden’s inaction on Line 3, and commented on the Democracy Now! news hour on Biden’s appointment of the first Native American cabinet member in history, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland:

“Joe, if you appoint Indian people, don’t just make them pretty Indian people that sit in your administration. Let them do their job. Indigenous thinking is what we need in the colonial administration. That’s when change happens.”

In British Columbia, Canada, the Wet’suwet’en sovereign nation has been resisting the multibillion-dollar Coastal GasLink pipeline being constructed by TC Energy. Just this week, Canadian federal police raided a multi-month blockade, smashing into a cabin with an axe and a chainsaw and arresting the land defenders inside. Police then burned the cabin to the ground.

This myth of that abundant shared meal 400 years ago continues to mask misery, from poverty and substance abuse to the epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women. But native communities are resilient and organized, and rising up in resistance. For this, we should all give thanks.

Common Dream’s work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License. Feel free to republish and share widely.

[content id=”79272″]