Source: The Conversation

In 2021, an expedition off the icy northern Greenland coast spotted what appeared to be a previously uncharted island. It was small and gravelly, and it was declared a contender for the title of the most northerly known land mass in the world. The discoverers named it Qeqertaq Avannarleq – Greenlandic for “the northern most island.”

But there was a mystery afoot in the region. Just north of Cape Morris Jesup, several other small islands had been discovered over the decades, and then disappeared.

Some scientists theorized that these were rocky banks that had been pushed up by sea ice.

But when a team of Swiss and Danish surveyors traveled north to investigate this “ghost islands” phenomenon, they discovered something else entirely. They announced their findings in September 2022: These elusive islands are actually large icebergs grounded at the sea bottom. They likely came from a nearby glacier, where other newly calved icebergs, covered with gravel from landslides, were ready to float off.

This was not the first such disappearing act in the high Arctic, or the first need to erase land from the map. Nearly a century ago, an innovative airborne expedition redrew the maps of large swaths of the Barents Sea.

The view from a zeppelin in 1931

The 1931 expedition emerged from American newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst’s plan for a spectacular publicity stunt.

Hearst proposed having the Graf Zeppelin, then the world’s largest airship, fly to the North Pole for a meeting with a submarine that would travel under the ice. This ran into practical difficulties and Hearst abandoned the plan, but the notion of using the Graf Zeppelin to conduct geographic and scientific investigations of the high Arctic was taken up by an international polar science committee.

The airborne expedition they devised would employ pioneering technologies and make important geographical, meteorological and magnetic discoveries in the Arctic – including remapping much of the Barents Sea.

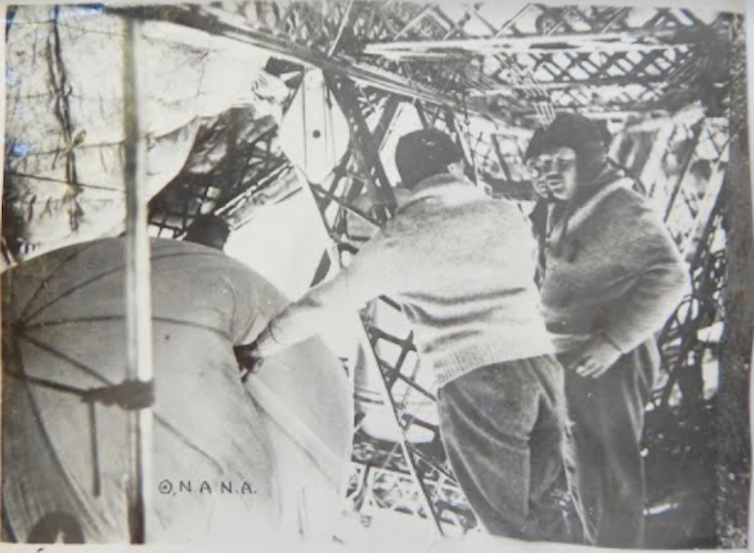

The expedition was known as the Polarfahrt – “polar voyage” in German. Despite the international tensions at the time, the zeppelin carried a team of German, Soviet and U.S. scientists and explorers.

Among them were Lincoln Ellsworth, a wealthy American and experienced Arctic explorer who would write the first scholarly account of the Polarfahrt and its geographical discoveries. Two important Soviet scientists also participated: the brilliant meteorologist Pavel Molchanov and the expedition’s chief scientist, Rudolf Samoylovich, who performed magnetic measurements. In charge of the meteorological operations was Ludwig Weickmann, director of the Geophysical Institute of the University of Leipzig.

The expedition’s chronicler was Arthur Koestler, a young journalist who would later become famous for his anti-communist novel “Darkness at Noon,” depicting totalitarianism turning on its own party loyalists.

The five-day trip took them north over the Barents Sea as far as 82 degrees north latitude, and then eastward for hundreds of miles before returning southwestward.

Koestler provided daily reports via shortwave radio that appeared in newspapers around the world.

“The experience of this swift, silent and effortless rising, or rather falling upwards into the sky, is beautiful and intoxicating,” Koestler wrote in his 1952 autobiography. “… it gives one the complete illusion of having escaped the bondage of the earth’s gravity.

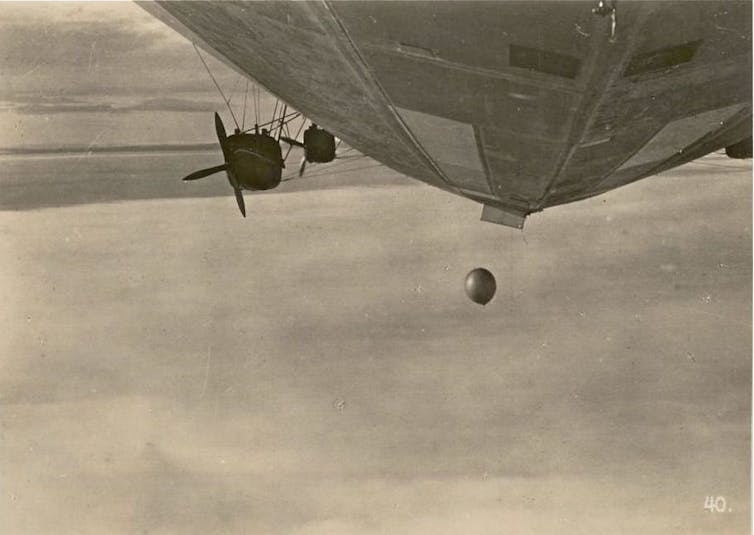

“We hovered in the Arctic air for several days, moving at a leisurely average of 60 miles per hour and often stopping in mid-air to complete a photographic survey or release small weather balloons. It all had a charm and a quiet excitement comparable to a journey on the last sailing ship in an era of speed boats.”

‘The disadvantage of not existing’

The high latitude regions the Polarfahrt passed over were incredibly remote. In the late 19th century, Austrian explorer Julius von Payer reported the discovery of Franz Josef Land, an archipelago of nearly 200 islands in the Barents Sea, but initially there had been doubts about Franz Josef Land’s existence.

The Polarfahrt confirmed the existence of Franz Josef Land, but it would reveal that the maps produced by the early explorers of the high Arctic had startling deficiencies.

For the expedition, the Graf Zeppelin had been outfitted with wide-angle cameras that allowed detailed photography of the surface below. The slowly moving Zeppelin was ideally suited for this purpose and could make leisurely surveys that were not possible from fixed-wing aircraft overflights.

“We spent the remainder of [July 27] making a geographical survey of Franz Josef Land,” Koestler wrote.

“Our first objective was an island called Albert Edward Land. But that was easier said than done, for Albert Edward Land had the disadvantage of not existing. It could be found on every map of the Arctic, but not in the Arctic itself …

“Next objective: Harmsworth Land. Funny as it sounds Harmsworth Land didn’t exist either. Where it ought to have been, there was nothing but the black polar sea and the reflection of the white Zeppelin.

“Heaven knows whether the explorer who put these islands on the map (I believe it was Payer) had been a victim of a mirage, mistaking some icebergs for land … At any rate, as of July 27, 1931, they have been officially erased.”

The expedition would also discover six islands and redraw the coastal outlines of many others.

A revolutionary way to measure the atmosphere

The expedition was also remarkable for the instruments Molchanov tested aboard the Graf Zeppelin – including his newly invented “radiosondes.” His technology would revolutionize meteorological observations and led to instruments that atmospheric scientists like me rely on today.

Until 1930, measuring the temperature high in the atmosphere was extremely challenging for meteorologists.

They used so-called registering sondes that recorded the temperature and pressure by weather balloon. A stylus would make a continuous trace on paper or some other medium, but to read it, scientists would have to find the sonde package after it dropped, and it typically drifted many miles from the launch point. This was particularly impractical in remote areas such as the Arctic.

Molchanov’s device could radio back the temperature and pressure at frequent intervals during the balloon flight. Today, balloon-borne radiosondes are launched daily at several hundred stations worldwide.

The Polarfahrt was Molchanov’s chance for a spectacular demonstration. The Graf Zeppelin generally flew in the lowest few thousand feet of the atmosphere, but could serve as a platform to release weather balloons that could ascend much higher, acting as remotely reporting “robots” in the upper atmosphere.

Molchanov’s hydrogen-filled weather balloons provided the first observations of the stratospheric temperatures near the pole. Remarkably, he found that at heights of 10 miles the air at the pole was actually much warmer than at the equator.

Fate of the protagonists

The Polarfahrt was a final flourish of international scientific cooperation at the beginning of the 1930s, a period that saw a catastrophic rise of authoritarian politics and international conflict. By 1941, the U.S., Soviet Union and Germany would all be at war.

Molchanov and Samoylovich became victims of Stalin’s secret police. As a Hungarian Jew, Koestler would have his life and career shadowed by the politics of the age. He eventually found refuge in England, where he built a career as a novelist, essayist and historian of science.

The Graf Zeppelin continued in commercial passenger service principally on trans-Atlantic flights. But one of history’s most iconic tragedies soon ended the era of zeppelin travel. In May 1937, the Graf Zeppelin’s younger sister airship, the Hindenburg, caught fire while trying to land in New Jersey. The Graf Zeppelin was dismantled in 1940 to provide scrap metal for the German war effort.![]()

Kevin Hamilton, Emeritus Professor of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Hawaii

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[content id=”79272″]