Earthquakes in the Nenana Basin region of Interior Alaska last longer and feel much stronger than a quake of comparable magnitude would in a non-basin region, due to the behavior of the seismic waves once they reach the area.

That’s because the seismic waves get amplified as they bounce back and forth off the sides and bottom of the sedimentary basin, which is deeper than Denali is high and contains millions of years of fill material.

Research about the Nenana Basin conducted by former University of Alaska Fairbanks Ph.D. student Kyle Smith was published in December in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Smith’s adviser, UAF Geophysical Institute seismology professor Carl Tape, is a co-author on the paper, along with associate professor Victor Tsai of Brown University in Rhode Island.

The Nenana Basin is one of the deepest in Alaska. The scientists found that seismometers overlying the basin’s deepest areas recorded stronger low-frequency amplification and that monitors at the basin’s shallow edges recorded minimal amplification as the seismic waves ricocheted inside the basin. They also found that higher frequency amplification occurs at monitors over both deeper and shallower areas.

“That reverberation is what is making the ground motion last longer,” Tape said. “And the slowing down of the waves is what makes it feel stronger.”

“In many places around the world — Tokyo, Mexico, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay, the Puget-Willamette lowland in Oregon, Seattle — it’s all the same thing: sedimentary basins near active seismic areas,” Tape said. “All those places have enhanced hazards, because they are in sedimentary basins.”

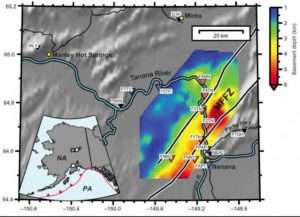

The researchers analyzed data from 48 local and regional earthquakes recorded by 13 temporary broadband seismic monitors installed in the Minto Flats seismic zone from 2015 to 2019. The monitors, the first seismic stations installed in Minto Flats, are part of the Fault Locations and Alaska Tectonics from Seismicity project funded by the National Science Foundation.

They cataloged the wave behavior of those earthquakes, which included magnitude 3 and 4 earthquakes beneath the basin and several regional earthquakes greater than magnitude 6.

Cataloged earthquakes also included some considered exotic: very low-frequency earthquakes, not previously seen in strike-slip faults such as those below the Nenana Basin, and earthquakes immediately preceded by a “nucleation” signal, a sign that an earthquake is about to occur. Those events make the fault zone and basin geologically exceptional and add to the researchers’ understanding of the basin’s influence on seismic wave behavior, Tape said.

The deep sedimentary basin is located in the Minto Flats fault zone, one of three zones in Alaska’s central region. Others to the east are the Fairbanks and Salcha zones.

The basin, 56 miles long and 7.5 miles wide, lies west of Nenana and south of Minto. It is nearly 4.5 miles deep, making it one of the deepest in mainland Alaska. Denali, North America’s tallest peak, rises about 3.85 miles above sea level just 125 miles southwest of the Nenana Basin’s center.

The basin sits between two active faults parallel to its length. It was defined in 2015 as a transtensional basin, a type in which the bedrock pulls apart and thins.

The basin is believed to have formed 66 million to 84 million years ago in the early Cenozoic or late Mesozoic eras, when Alaska had a warmer and wetter climate than today. Sediment has filled it since then. David Barnes of the U.S. Geological Survey discovered it in 1961 during gravity anomaly surveys.

A commercial core sample from about 2 miles deep revealed just under a mile of gravel deposited by the Tanana River over the past 6 million years. It is likely that the process continues today, with the basin sinking and continuing to accumulate sediments.

“It’s that unconsolidated pile that is causing these seismic effects that are so profound,” Tape said.

Scientists have long known that basins affect seismic waves. The catalog of Nenana Basin seismic wave behavior provides a way for seismologists to improve their understanding of some of the world’s nearly 800 known sedimentary basins.