|

|

|

Energy deficiencies and inflammation may cause warming-related mortality in Pacific cod larvae.

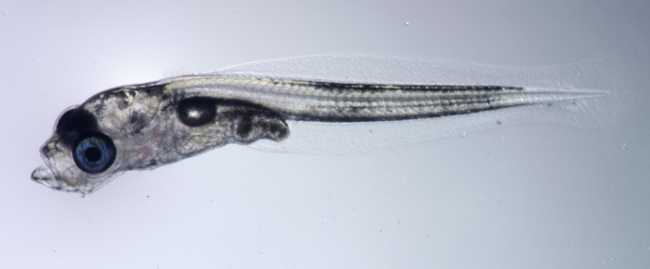

A new study used gene expression analysis to explore how temperature and ocean acidification affect Pacific cod larvae. Scientists discovered that larvae are equipped with genes that allow them to survive cool and acidified conditions. However, warming may cause mortality by depleting energy and triggering inflammatory responses. These mechanisms are possible links between changes in ocean conditions and the recruitment of young fish in the Gulf of Alaska Pacific cod population.

Decrease in Pacific Cod Population

Pacific cod is a highly valued commercial fishery, and cod also play a key role in the ecosystem as both predator and prey. However, cod populations in Alaska have declined in recent years. Decreased population size is likely linked to recent marine heat waves, and early life stages seem to be the most impacted. Scientists predict that marine heatwaves may be more common in the future and that ocean acidification will intensify, particularly at high latitudes.

Experiments have shown that Pacific cod are sensitive to temperature during their early life stages. Temperature influences how their eggs develop, how their bodies use energy, and how they grow and survive as larvae. We don’t know as much about the impacts of ocean acidification.

In a 2024 study at the NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center, scientists raised Pacific cod from embryos to larvae at multiple temperatures (3°C, 6°C, 10°C). To examine the potential interaction between temperature and ocean acidification, they also raised them in water that replicated current ocean conditions and in more acidified conditions. This mimicked conditions projected for the end of this century. The study found that larval mortality was very high in warm water but the effect of acidification was more complex.

The effects of temperature and acidified conditions depended on the fish’s development stage. Scientists need to better understand how changing ocean conditions can affect important species like Pacific cod, and whether these species can adapt to these changes.

A Deeper Dive with Gene Expression

This new molecular study examined larvae to understand why heat wave temperatures might cause larvae to die at high rates. “Finding larvae that are dying in the field is very unlikely, but we were able to sample experimental larvae that we knew were dying rapidly due to warming,” said Emily Slesinger, researcher at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center. They also sampled larvae exposed to other conditions. The experiments simulated more acidified water and colder temperatures which Pacific cod larvae currently experience in some regions and years. Slesinger continues, “The unique thing about this study’s approach is to look beyond whether these larvae live or die under different conditions, but to understand why through gene expression analysis.”

Fish hatch with a fixed set of genes that stays the same throughout their lives. But which of those genes are turned on or turned off can change dramatically as they grow or respond to their environment. When genes are “expressed”—meaning they’re being used to make proteins—they influence how cells work, how organs function, and how energy is used throughout the body.

“Temperature has a big effect on gene activity, especially in cold-blooded species like fish with body temperatures that shift with the water around them,” said Laura Spencer of the University of Washington, who led the molecular analysis. “In our study, we looked at which genes larval cod were actively using under different temperatures and levels of acidification. By comparing those patterns, we can identify why larvae are so sensitive to warming, and how they cope with acidified and cold conditions.”

The gene expression data suggests that warming water temperature increases larval mortality due to two main factors: energy shortages and inflammation. Warming increases the body’s energy needs due to faster growth and development, and a higher metabolic rate. At the same time, warming appears to induce inflammatory and immune‐related processes, which are themselves energetically costly. These energetic needs can exceed available fat stored in their tissue and in their food. In extreme cases, the larvae can starve to death.

If larvae experience warming and acidification together, temperature appears to be the main driver, although acidification might affect proteins in their red blood cells. Acidification on its own appears unlikely to directly increase mortality. But the gene expression data show that acidification could affect the larvae’s ability to absorb fat in the intestine. This could explain why larvae in the acidification treatment were slightly thinner. It may be more important for their survival in the wild, where food availability can be limited.

Larvae in colder waters, such as those spawned farther north or earlier in the spring, increase their production of enzymes and proteins. This response likely helps compensate for slower metabolism and slower biochemical reactions at low temperatures. However, growth and development are still much slower in the cold, which can reduce how many young fish survive long enough to recruit into the fishery. Other work has shown that Pacific cod probably would not survive sub-zero temperatures, since their blood lacks antifreeze properties found in some cold-tolerant fish.

Genes identified in this study could be important to the future of Pacific cod. Some populations may have genetic traits that help them adapt to warmer, colder, or acidified spawning locations. “Overall, warming appears to be the main factor affecting cod larval physiology, and this could impact future growth of the population,” said Spencer.

Alaska Fisheries Science Center | NOAA Fisheries

|

|

|