Early in his career, on a wet, windy, foggy night, Guy Tytgat checked into the loneliest hotel in the Aleutians. His room was four feet wide and five feet tall, made of fiberglass, and perched on the lip of a volcanic crater.

Tytgat did not enjoy the evening he shared with 420 pounds of batteries, an antenna and seismic equipment, but he is thankful the little gray hut was there.

Tytgat is a geophysicist with the Alaska Volcano Observatory at UAF’s Geophysical Institute. For more than 20 years, he has installed and repaired seismic stations across Alaska, from 14,000 feet high on Mount Wrangell to Umnak Island in the Aleutians.

In the early 2000s, he spent the night crammed in an equipment hut on a volcano. Over an outdoor lunch, he recently told a story of when Alaska fieldwork does not go as planned.

The equipment huts, the size of a chest freezer turned on its side, contain seismometers that allow scientists at AVO to monitor the rumbles of distant volcanoes from their offices in Anchorage and Fairbanks. Also enclosed in the huts are computers, antennas, batteries, and radios to transmit earth-motion and other data to relay stations.

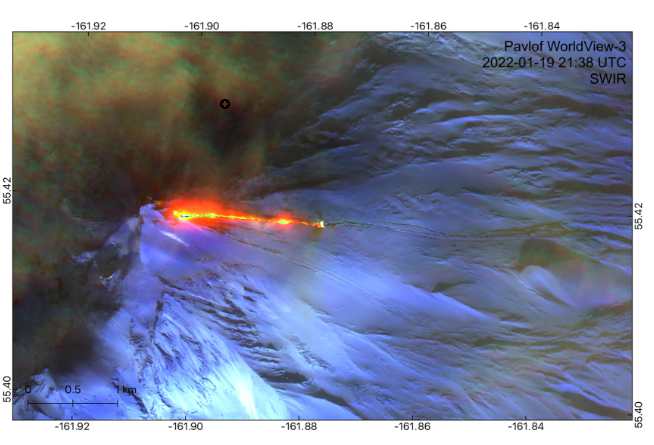

Tytgat, who is in late-August 2020 headed to Wake Island in the Pacific Ocean to work on infrasound equipment, was years ago on Umnak Island to finish up a seismic network on the flanks of Okmok Volcano.

While working on a station lower on the island, he noticed that the rim of Okmok crater was visible, with blue sky in the background. A hut on the rim needed solar panels installed. Sensing an opportunity, Tytgat grabbed them and jumped in a helicopter.

[content id=”79272″]

The helicopter pilot dropped him near the hut on the crater rim. Tytgat pulled out the solar panels, his toolbox, and a waterproof bag full of survival gear. The pilot then took off. He found a less-precarious place to park the helicopter.

While Tytgat worked on the solar panels, dense fog crept in.

When he finished, Tytgat called over his radio to the helicopter pilot, who gave Tytgat the GPS coordinates of where he was perched.

By that time, about three hours after he had installed the solar panels, Tytgat was wet, cold, and not sure he could reach the helicopter’s new, lower location by the time darkness fell. He then made the difficult decision to retreat to the seismic station, which would provide some shelter.

His GPS guided him back to the hut, which was then streaked with rain and vibrating in the wind. He creaked open the door, stepped in, pulled his dry-bag inside, and slammed it shut.

Once inside the dark chamber, Tytgat pulled fresh clothes and a sleeping bag from the dry bag he never leaves a helicopter without. He wriggled into warm clothes and a sleeping bag, and then tried to get comfortable on a narrow bench.

The hut was watertight, but condensation dripped from the ceiling. Adding to his anxiety were memories of two huts that he had just visited — lighting had struck and destroyed one. Wind had ripped another from its cement footings and blew it over a cliff.

“I was pretty nervous,” he said. “Either I could get hit by lightning or blown off the mountain.”

[content id=”79272″]

After a retched night, Tytgat crawled from the hut in the morning to see nothing but fog. Knowing he needed to make the most of his daylight, he leaned into the wind and started hiking along the rim of the volcano.

Then, through a hole in the fog, the helicopter pilot landed and retrieved him.

They descended. Tytgat spent much of the day warming himself by a woodstove at a ranch belonging to a family living on the island.

Looking back on his night in that box atop Okmok, Tytgat said it confirmed that a field hand’s survival bag is sometimes his or her best friend.

“I wouldn’t go out without it,” he said.