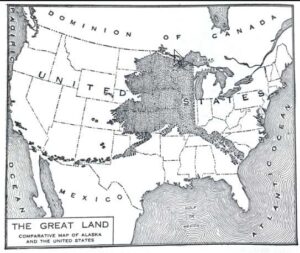

A Guide to Alaska, published in 1943, includes this comparison map of Alaska and the Lower 48 states.

In 1935, in the middle of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Federal Writers’ Project.

His goal was to provide jobs for American writers who found themselves unemployed after the stock market crash of 1929.

Merle Colby was one of those writers. As the U.S. economy tanked, his freelance work for the Atlantic and other publications dried up. He must have been ecstatic when officials named him one of the participants in the Federal Writers’ Project.

Writers chosen for the project profiled U.S. states and territories in books meant for potential visitors to those places. Colby’s assignment was to write a guidebook for the territory of Alaska.

Colby, who lived in Massachusetts, traveled to Alaska by train and steamship in the late 1930s. When he was writing the book, there was no highway connecting Alaska to the Lower 48. The road then ended a few hundred miles short of Alaska, in Hazelton, British Columbia.

A historical novelist and fiction writer, Colby filled 500 pages of A Guide to Alaska with his descriptions of the territory and the 60,000 people that lived in it.

Colby wrote pages dispelling the usual myths about people living in igloos and a bipolar world of six months of light or darkness. He observed things as he saw them and ended up with a realistic portrait of Alaska and the people who lived here.

“The long midsummer day is rather wearing on Alaskan nerves,” he wrote. “After summer-long, midnight berry picking or swimming excursions, most residents of northern Alaska are glad to see the days shortening again.”

Colby’s observations of natural Alaska also hold up well after 80 years. He described the Aleutian Low, “a trough of low pressure (responsible for) a great many of the cyclonic disturbances of the northern hemisphere.”

He was also aware of permafrost, “a peculiar surface condition. In many places the subsoil to a depth of several hundred feet is permanently frozen.”

Colby was also prescient in noticing the value of Alaska’s great swamps, such as the Arctic (North) Slope, which “contains very extensive wild fowl breeding grounds, which play an important part in maintaining the (waterfowl and songbird) resources over a large section of the United States.”

The Alaska of the time Colby visited was decades past the gold rush but still 20 years short of becoming a state. During that in-between time soon to be jarred by World War II (which would double Alaska’s population), Colby portrayed the territory as a place still inventing itself.

“Being present toward the beginning rather than toward the end of a phase of the life-process is a new sensation for most of us sons and daughters of industrial civilization,” he wrote. “Alaskans feel that sensation every few years when . . . the Great Land suddenly wrinkles its hide and the needle of the seismograph at the University of Alaska swings to register an earthquake.

“A smoking volcano in the Aleutians becomes ominously clear, and ash and superheated gases burst out of monster vents, as at Katmai, where there took place in 1912 what geographers believe to be the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history.

“Or in the glacier country a few million tons of ice recede, hills and valleys are uncovered, and for the first time in thousands of years the sun warms the earth, a spruce seed falls, and the process of life begins.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell ned.rozell@alaska.edu is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.