Ned Rozell found this obsidian flake at an archaeological site in the Nogahabara Dunes.

NOGAHABARA DUNES — Karin Bodony has walked us to a sandy bowl, a place she has perhaps visited more than any other living person.

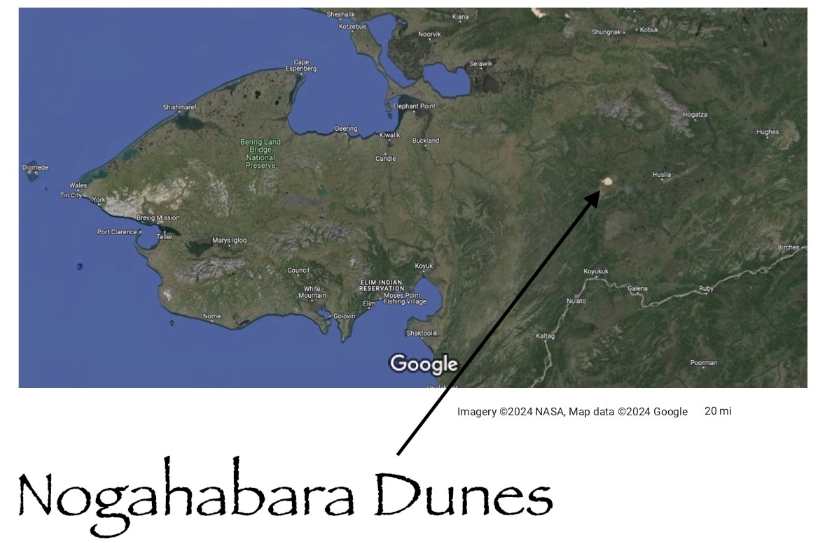

Karin is a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who lives in the village of Galena, 70 air miles south and east of here. Today, she has led three of us back to a blank spot in this vast oval of sand.

Here, on a dim, rainy afternoon 23 years ago, she and University of Alaska Fairbanks insect specialist Jim Kruse were walking through, on the way back to their camp in the distant woods after collecting bugs on the dunes.

As they hiked toward one lonely spruce tree that had somehow thrived in the desert, Karin peeled off to look at a strange smattering of rocks on top of the sand. Hundreds were scattered in a circle less than 20 feet across.

Karin felt right away she had stumbled into something remarkable — a site richer than many archaeologists will encounter during their entire careers. She and Kruse dropped to their knees for a better look at a variety of oval tools someone had chipped from glassy volcanic rock long ago.

Those knives and spear tips allowed people to pierce the hides of large mammals thousands of years before the first metal knives would appear in Alaska.

At the time of her initial visit here in July 2001, Bodony still carried her maiden name of Lehmkuhl. She was a researcher on her first trip to these seldom-visited ancient sand dunes easily visible from space.

On that day, she and Jim Kruse were among a team of eight people exploring the dunes, with the other six wandering elsewhere. They were all recording the unique flora and fauna of the dunes. Among them were the tiger beetles Kruse found that were later determined to be a subspecies unique to Nogahabara — a relic of the last ice age.

Twenty-three years later, Karin has visited the dunes more than a dozen times. On this July day in 2024, she has walked with me, her 15-year-old daughter Ida, and seasonal Koyukuk National Wildlife Refuge biologist Ryan Potter on a two-hour jaunt from our forested campsite off the active dunes.

We notice a different feel when Karin tells us we have arrived at the archaeological site.

“There’s been people here,” Ida says over the whisper of a chilly wind that flows unimpeded from a green valley west of the dunes.

I don’t know what prompted Ida to say that, but I feel it too.

As the father of a daughter a little older than Ida, over the last week I have been impressed at Ida’s indifference to mosquitoes, and her answers to questions her mother asks as Ida has measured water chemistry at nearby lakes. There have been a few teenage moments — such as when she rolled down a dune like a log to escape the seated old people complaining about cell phones — but she belongs out here in the bush.

In the years after her 2001 find, Karin led several archaeologists to this spot. They sifted this sand through screens and collected most of the obsidian pieces. A few dozen of them are on display at the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

Today, Karin immediately finds a few glassy flakes the size of her thumbnail.

She hands them to me. I cup them in my palm, wondering who might have chipped these fragments from a knife or hide scraper.

Former University of Alaska Fairbanks archaeologist Dan Odess and Jeff Rasic of the National Park Service also found a few animal bones here that were at least 10,000 years old, suggesting that people ate those animals as the last ice age was waning.

That’s a long time ago, and this is a good place to ponder who these people were — and what they were doing here in this desert.

“There is no obvious attraction today for repeated use of this location, such as a nearby water source or prominent viewpoint,” wrote Rasic and Odess in a 2007 paper about the site and the 257 pieces they recovered.

The richest archaeological sites are often on prominent hilltops that are as appealing to people today as they were thousands of years ago. This spot had to be stumbled upon. Karin was the one to do it.

As we walk the sand without talking, I think of ancient people pressing down on the same ground. We all squint, looking for chips of rock someone carried from a volcanic mountain in middle Alaska, 95 miles east of us, father up the Koyukuk River valley.

The obsidian rock found here was from Batza Tena, one of only a few quarries in Alaska where people found such volcanic glass. Archaeologists find this obsidian at sites all over Alaska, as if ancient people had traded seal oil or dried fish or some other local resource for it.

I had been looking forward to this day, our last at the dunes during a week-long trip and one with no rain. I had known bits and pieces of Karin’s discovery story, but it is a career moment for me to hear her tell it at the site.

She says she believes the theory of the archeologists who visited here — Rasic and Odess — that some ancient group of people was carrying a tool kit of different obsidian pieces when they arrived here. Maybe they carried all those objects together in a leather pouch or two; many of the pieces have tiny, circular fractures that suggest they were bumping against one another.

“I think they were camped here, and maybe left (the tool kit) to come back to — and for some reason didn’t make it back,” Karin says. “It isn’t an easy place to find.”

In a rebuttal to Rasic and Odess’s toolkit paper, other archeologists argued that the obsidian may have been left over many years by different generations of people. But no one really knows why all those pieces were set down right here in a sea of sand where few modern people have walked.

We spend our hour at the site not finding anything more than the first tiny pieces, except for dead willow leaves that had blown in.

Right when I give up, the toe of my boot pushes something hard.

I reach down and pick up an object the size of a potato chip. I blow sand off and notice a lustrous, razor-edged rock.

“Karin!”

She walks over. Ida and Ryan follow.

“Wow, there it is,” she says.

We all hold the rock, possibly a discarded flake from a finished tool, but with an edge sharp enough edge to still slice flesh.

We hold it to the sun; the light illuminates the rock.

For many years, I have stared at ground all over Alaska. This is the first piece of human-worked obsidian I have found.

“I wonder who was the last person to touch this rock?” I say.

“It was me, about 30 seconds ago,” Ida says.

We crack up.

Then I place the flake back on the sand where it rested for who knows how many years.

After a last few looks back at the site, we walk across the dunes for the last time, heading back to our camp.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.

[content id=”79272″]