Earthquakes have a well-known and easily recognizable connection to volcanoes. The sudden onset of ground shaking can indicate near-term or imminent volcanic activity.

Earthquakes have a well-known and easily recognizable connection to volcanoes. The sudden onset of ground shaking can indicate near-term or imminent volcanic activity.

Volcanic tremors, however, are difficult to detect. These are semi-continuous seismic or acoustic signals, or both, that continue for just a few seconds or persist for a year or more.

They, like earthquakes, carry information about activity within and below a volcano.

Graduate student researcher Darren Tan at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute is researching a way to improve tremor detection and to also classify them.

“Volcanic tremor tends to have a gradual emergent onset, which traditional earthquake detection algorithms struggle to detect,” Tan said. “So what is required for seismologists to detect them is visual scanning of spectrograms.”

Visual scanning is a time-consuming task done manually every day at the Alaska Volcano Observatory. The observatory is a joint program of the UAF Geophysical Institute, the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys and the U.S. Geological Survey. The USGS funds the observatory, part of which is based at the Geophysical Institute.

Tan’s research, which he is presenting Monday at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, will automate that scanning through machine learning methods.

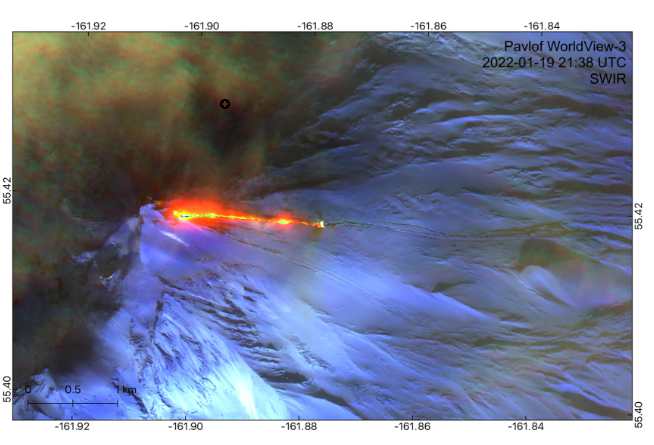

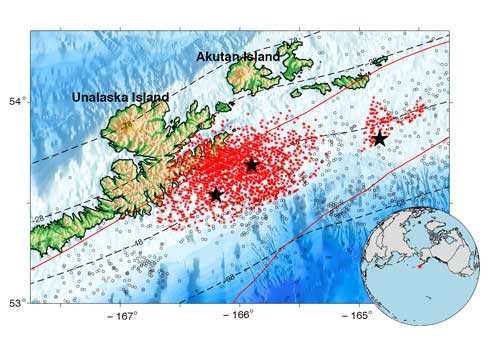

Tan drew upon the diversity of tremor signals from the 2021-2022 eruption of Pavlof Volcano, on the Alaska Peninsula, to build an extensive dataset of labeled seismic and low-frequency acoustic spectrograms. Those spectrograms represent a variety of classifications such as tremor type, explosions and earthquakes, which are then used to train a computer model for each data type.

The trained models will then be able to detect and classify the volcanic tremors in near real time.

Humans will still be involved in interpreting what the automation produces, however.

“We want to try it out on Alaska volcanoes but at the same time do it sensibly,” Tan said. “We don’t want to lose touch with interpretation.”

Tan’s research is funded by a National Science Foundation eruption forecasting project.

Tan was born and raised in Singapore, where he also completed his undergraduate work at Nanyang Technological University. He was in the third cohort of what at the time was a new Earth systems science degree at the university.

“I had a really unique opportunity. I was on a research scholarship that helped me do semester-long research projects as an undergrad,” he said. “That gave me an early opportunity to dip my toes into research.”

That scholarship came with an opportunity to do his doctoral thesis abroad. With the help of his mentor, he landed at the Cascades Volcano Observatory in Washington state.

That created an opportunity for him to connect with USGS people, specifically in the agency’s Volcano Observatory Network. It was near the end of his work at the Cascades observatory that he learned the Alaska Volcano Observatory was looking to hire a cohort of doctoral students for a program funded by the National Science Foundation.

And that began his time in Alaska.

[content id=”79272″]