An outburst from Mendenhall Glacier floods northern Juneau, Alaska, on Aug. 6, 2024. Water overtopped the banks of the Mendenhall River for the second consecutive year.

With his eyes on Alaska weather and climate for many years, Rick Thoman saw a need for a recent update on what is happening within America’s largest state.

“Alaska was being hammered with extreme events,” he said.

That resulted in the publication of Alaska’s Changing Environment 2.0, a product of the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Thoman has worked there for six years after many more as a National Weather Service meteorologist in the Fairbanks office.

The 32-page publication — which Thoman produced with his colleague Heather McFarland — tells the story of a place that’s changing as fast as anywhere on Earth.

Here are some of those recent observations, from Thoman’s own research and that of a few dozen other experts.

From the start of record-gathering in about 1900, Alaska’s long-term average yearly temperature remained the same until the mid 1970s. Since 2010, Alaska has experienced six of its top 10 warmest years. The last year that ranked in the top 10 of Alaska’s coldest years was 1975.

During the past 50 years, the greatest warming happened on Alaska’s North Slope and western coast. Not coincidentally, sea ice that forms on the ocean off the western and northern coasts of Alaska is shrinking in extent, duration and thickness.

The Bering Sea ice season is now 41 days shorter than it was in the 1970s. This floating white jigsaw puzzle that is a natural refrigerator for the planet forms 23 days later in fall and melts 18 days earlier in summer.

Thoman and McFarland devoted several pages to recent avalanches, landslides, floods, rain-on-snow days and storms that wrack coastal communities. They listed 31 of these extreme events since 2019.

There was no place in Alaska to hide: Juneau’s Mendenhall Valley residents experienced glacial outburst floods the past two Augusts, three huge snowstorms in 11 days made life hard in Anchorage in December 2022 and rain that splattered on supercooled snow and roads turned Fairbanks into an ice rink in December 2021.

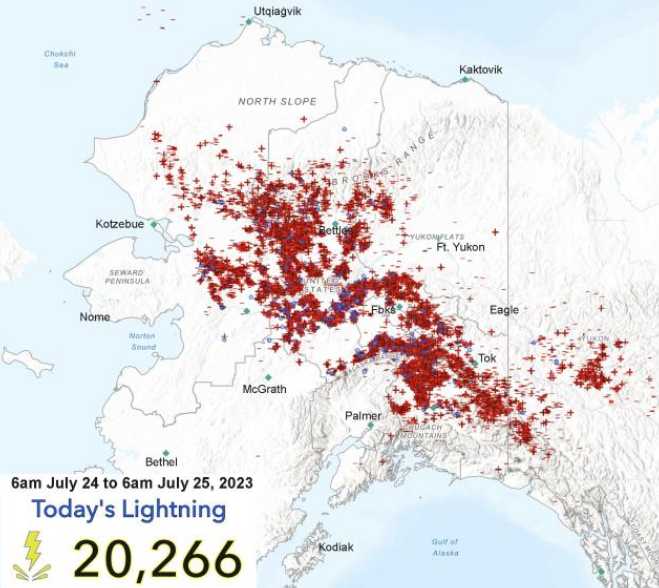

Alaska is getting smokier. Since 2000, people in Fairbanks have enjoyed only two summers that were free of forest-fire smoke.

Fire seasons featuring more than 2 million acres burned are twice as common now as they were 30 years ago.

Gardeners may appreciate that their growing season in Fairbanks and Palmer is four weeks longer on average than it was in the early 1900s.

Ocean waters off Alaska are following the worldwide trend of warming, but some of the numbers are “astounding.” Thoman used that word to describe Kotzebue Sound averaging 12.1 degrees Fahrenheit warmer in summer than it was in the 1980s. That warming is due to the loss of sea ice earlier in the spring and summer, allowing sun to heat the dark ocean, as well as rivers dumping more warmth into the sound.

The Riley Creek Fire burns in Denali National Park and Preserve in July 2024. The fire consumed more than 400 acres.

High sea-surface and warm river temperatures are one factor in the decline of Yukon River Chinook and chum salmon to the point where fish camps are abandoned. The remaining fish are smaller and are laying fewer eggs than in the recent past.

With less sea ice, polar bears are spending more time on land. In the southern Beaufort Sea, 30 percent of monitored polar bears were onshore in summer 2020 compared to 5 percent in 1985.

Polar bears’ main food source, seals that live on or near the ice, seem to be doing well. The average blubber thickness — which biologists use to determine the health of seals — is about the same within seals that hunters harvested along Alaska’s coast between the 1960s and 2023.

For all the documented decreases in animal numbers in Alaska, there are a few species bucking the trend. The snow goose population is exploding in summer along the Ikpikpuk and Colville river mouths of northern Alaska. Biologists for the U.S. Geological Survey documented a population of about 40,000 adults between 2019 and 2023. Fewer than 500 adult birds nested there when researchers began counting them in 2005.

Alaska’s Changing Environment 2.0 is available on the ACCAP website.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.

[content id=”79272″]