Fifty-five summers ago, when Dave Klein first stepped on St. Matthew Island, driftwood on the beaches held no plastic bottles and hundreds of reindeer roamed the tundra hills.

|

| St Matthew Island-USF&W |

When the 85-year-old naturalist returns next week for his sixth trip to one of the most remote islands of the world, he knows he’ll see lots of plastic and no reindeer, along with some changes he can’t yet imagine.

“It’s such a fabulous place,” he said.

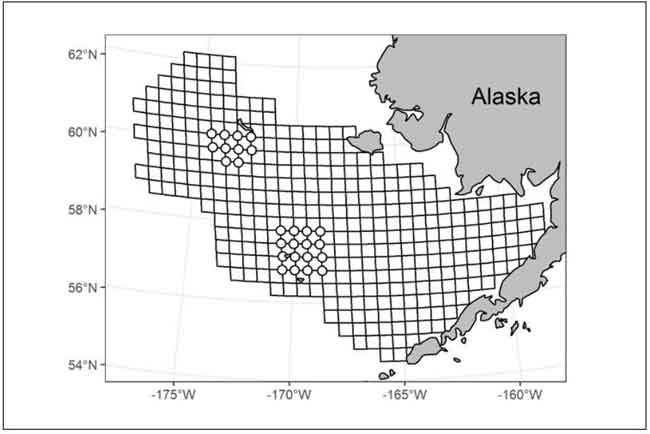

Klein, along with a group of scientists and one non-scientist (me!), are headed to the Bering Sea to survey the life in a place separated by more than 200 miles from the nearest landfall. Captains with the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge will ferry us on the refuge’s ship the Tiglax to St. Matthew from the island of St. Paul, about 225 miles and 24 hours away.

Refuge biologists try to return to the island every five years or so, but St. Matthew — north of the Pribilof Islands and south of St. Lawrence Island — is as difficult to reach now as it was in 1920, when biologist G. Dallas Hanna wrote the following:

“Owing to the distance of the islands from the regular channels of travel, opportunities for naturalists to visit it rarely occur. It is barren, treeless, uninhabited and surround by dangerous and poorly charted waters.”

|

|

No one knows the 30-mile long, three-mile wide island better than Klein, my friend and neighbor who first visited St. Matthew in 1957, before Alaska was a state. He hiked the length of the island then, documenting the success of reindeer the U.S. military had transported there from Nunivak Island. The reindeer were an emergency food source for a few dozen men stationed there to operate a weather station and radar-navigation site. When World War II ended, the men left and the reindeer remained. Without predators and with plenty of lichen, the island was a paradise for reindeer, which increased from the original 29 to 6,000 by the early 1960s. When the reindeer ate most of their lichen and faced a brutal winter in 1963 to 1964, the herd dwindled to 42. Forty-one were females; the other was a male that was unable to reproduce.

When Klein visited the island for the fourth time, in 1985, there were no reindeer. They had all died of starvation. He wrote a paper about the classic case of boom and bust. In 2010, he co-authored a paper on the terrible winter that helped finish the reindeer.

Polar bears that formerly lived on the island in summer are also one of Klein’s favorite study subjects. The island, surrounded by sea ice during winter and ice-free during summer, was the home of many polar bears until a little over one century ago, when crews from seal-hunting ships and a U.S. revenue cutter probably shot the last ones. Polar bear trails endure on the island, and conservationists have suggested St. Matthew as a possible sanctuary for polar bears.

Klein has ambitious study goals for this trip to the island. As St. Matthew was part of the Bering Land Bridge, he will, with the help of Rich Kleinleder, take core samples from marshy areas on the island to determine what ancient plant life grew there and what the climate might have been like in the distant past. He and others will also see if red fox, which have scampered to the island over the sea ice from mainland Alaska, have continued to replace the now-rare arctic fox, which was dominant on the island when Klein arrived in 1957.

|

|

Nine people will be on St. Matthew for nine days, including biologists for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who will trap fish from the rivers and lakes, take air quality samples, record the songs of McKay’s bunting (located only on St. Matthew), collect singing voles also endemic to the island and survey sea birds. Entomologist Derek Sikes of the University of Alaska Museum of the North will scramble over the island to “collect the (heck) out of it.” Anthropologist Dennis Griffin will investigate a few spots on the island for evidence of ancient people. Monte Garroute will collect island plants for the UA Museum and the Royal British Columbia Museum.

I will tag along with these guys, gathering fodder for this column and living out a dream to visit the island I’ve had since writing a decade ago that St. Matthew, 209 miles from the nearest village, is the most remote place in Alaska.