Just over the hill from Fairbanks is a broad, swampy lowland pocked with lakes and sliced by crooked brown streams. You could hide Anchorage in Minto Flats, home to more moose, beavers and northern pike than people.

The spongy surface of the flats is good for a few things: making mosquitoes and hiding the effects of frequent earthquakes. Seismologists can’t see any giant rips on the self-healing surface, but they know from how the earth shakes that two long faults lurk deep beneath the muskeg.

Scientists are so interested in the fault zone (which produces many of the shakes we feel in Fairbanks) that four of them embarked on a raft trip last August. For a few days, they floated into the heart of one of the largest geologic basins in Alaska.

Carl Tape is a seismologist at the Geophysical Institute of the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Along with State Seismologist Michael West, seismologist Matt Gardine and graduate student Celso Alvizuri, Tape shoved a blue raft off the gravel in Nenana last August and floated the Tanana River to Manley Hot Springs.

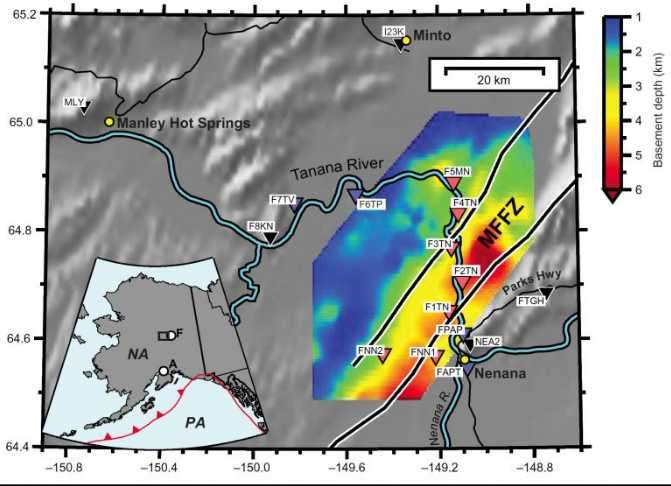

The four men embarked on the river trip because they have been funded to install one dozen sensitive ground-motion detectors in what they call the Minto Flats seismic zone. The best way to scout the area was to let the Tanana River carry them as the braided waterway makes a 90-degree bend northward from the town of Nenana.

Tape, who grew up in Fairbanks, was surprised at the remote feeling of that 100-mile river stretch just a few minutes from Fairbanks by plane. As their 14-foot raft rotated in the current, the scientists heard the groan of fish wheels and steered clear of a few barges steaming toward Nenana. When they hit shore, they saw many sets of bear tracks pressed into gray mud.

The scientists explored high and dry spots where they might locate their broadband seismometers and where radio systems might broadcast ground-motion information toward the ridge upon which the Parks Highway runs from Fairbanks to Nenana. On that hilltop, other stations will repeat the data and send it back to the Alaska Earthquake Center in Fairbanks.

Tape has been fascinated with the Minto Flats seismic zone since before he and his colleagues discovered that a magnitude 8.6 earthquake from Sumatra in April 2012 sent its energy through half the globe and triggered a magnitude 3.9 earthquake in the flats. The effect of that “Love wave” was another example of action on a Minto Flats fault capable of ripping a magnitude 7 or larger earthquake.

Residents of Minto (population 258), Nenana (391) and the camp at Old Minto (a few dozen at certain times of year) are the people most threatened by a Minto Flats earthquake. The new seismic stations, which will be active from May 2015 to August 2019, will help scientists ponder just how large of an earthquake is possible there.

Minto Flats is responsible for a magnitude 6 earthquake on October 5, 1995. Many people in Fairbanks remember that day as the most vigorous shaking they have felt, even more than from the much larger (but farther away) Denali Fault earthquake of 2002.

Tape says Fairbanks residents should be wary of Minto Flats, and the new seismometers will give experts a better idea of what earthquakes the area is capable of. The basin is also of great interest to corporation executives searching for oil and gas.

Tape and his partners will return to the lower Tanana River this summer in an attempt to install the first of the 12 seismic stations. This time, he says, they will not rely on gravity. They will instead run the river in a long aluminum boat with a powerful outboard motor, the preferred craft of the locals.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.