If we had begun exploring in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 2002, its oil and gas (and jobs and revenue) would be flowing now.

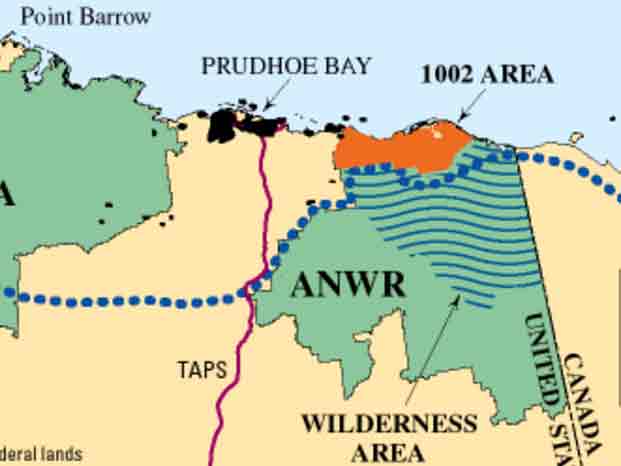

Ten years ago this week, the U.S. Senate debated whether to open a small section of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and natural gas production. Under the terms of the ANWR amendment, a maximum of 2,000 acres in the nonwilderness portion of the refuge (less than 0.01% of the whole) would have been opened to surface development. But the amendment was defeated, and we are paying the price today.

In an energy-strategy speech Tuesday, President Obama once again listed the importance of producing “more oil and gas here at home.” Whether that happens depends on what the president and other policy makers have learned since the ANWR debate a decade ago.

Despite Alaska’s stellar record of balancing energy production with environmental protection, opponents threw out a litany of excuses to oppose development in ANWR, none tethered to reason or reality. One senator urged her colleagues to think of the local wildlife, although wildlife has thrived on nearby state lands with oil and gas production. Another declared that there aren’t enough pristine areas left in the world, ignoring the fact that the federal government alone has designated nearly 110 million acres in the U.S. as wilderness.

Some chose to claim that America was running out of oil, as if that would be a compelling reason to ignore our largest untapped field. Others alleged that the proposed drilling area only holds a six-month supply of oil—both understating the size of the resource and strangely believing it would somehow be the sole source of oil for our entire country over that period.

But the most blatant excuse is one that officially expires this week. Because oil might take up to 10 years to reach market, we were told that the nonwilderness portion of ANWR could not be part of the solution to our energy challenges. Nearly every senator who spoke against the amendment in 2002 listed this as a factor in his or her decision.

Now, 10 years later, it is plain to see that the argument was not just wrong, but backward. Instead of being a reason to oppose development in ANWR, the time it takes to develop the resource should be treated as a reason to approve it as quickly as possible.

Consider what would be different today had the Senate agreed to open those 2,000 acres a decade ago. If production were coming online right now as expected, it would be providing our nation with a number of much-needed benefits—including a lot more oil.

Oil prices would be restrained, if not reduced, as Alaskan crude made up for both actual and threatened losses around the world. Billions of dollars in new revenues would be generated for the U.S. Treasury, reducing the deficit and providing us with a means to invest in new energy technologies.

Oil imports would be reduced, keeping dollars within our economy to promote growth here at home. Thousands of ANWR-related, well-paying new jobs would be created at zero cost to taxpayers. And a looming national catastrophe—the shutdown for economic reasons of the increasingly empty trans-Alaska pipeline—would be averted.

It’s a shame that we are forced to forgo these benefits at a time when all are desperately needed. But this is not just a missed opportunity; it’s a cautionary tale. The shortsighted decision made 10 years ago is relevant to the current debate on energy policy.

Today, we again find ourselves at a moment when federal policy makers could dramatically increase domestic oil and gas production. But instead of embracing that possibility, many of the same members of Congress are making the same antisupply arguments. What we should realize is that these are empty excuses that hurt our nation’s future prosperity.

It’s time to revisit whether ANWR itself should be opened to development. Opening ANWR is not a silver bullet that will unilaterally or immediately solve our energy challenges. To demand that sets an impossibly high bar that no resource or regulation can ever reach. Instead we should see ANWR for what it can provide in terms of energy, jobs, revenue and security.

I’m particularly hopeful that President Obama will lead the way by living up to his recent promise to allow oil production “everywhere we can.” If that’s not just election-year rhetoric, this tiny patch of tundra in northeast Alaska would be a perfect place to start.

Ms. Murkowski is a Republican Senator from Alaska.