Every year, on the fourth Thursday in November, Americans celebrate Thanksgiving. It’s a commemoration of the 1621 harvest feast when the colonists, who came from England, shared a friendly meal with the land’s Indigenous people.

In Plymouth, Massachusetts, site of the first Thanksgiving, historians and others try to separate fact from fiction surrounding the legend that grew out of that initial celebratory feast that took place more than 400 years ago.

“The problem with it is that there are so many stereotypes and so much misinformation that’s bundled into that story,” says Paula Peters, a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe whose ancestors are believed to have been at the first Thanksgiving. “It’s a story that really marginalizes the Wampanoag history.”

The pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower in 1620. By their second winter, they were struggling, until the Indigenous people taught them how to plant crops and live off the land.

“When we think about the pilgrims coming over, we forget about the aspect of the Wampanoag people helping them survive that winter, or even navigate this land, or navigate the waters, which is very important,” says Wampanoag Tribe member Malissa Costa, who oversees the Native American-themed exhibit at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums.

The living history museum, located a few kilometers from the site of the first Thanksgiving, also features a 17th-century English village. Actors dress up as pilgrims to depict the colonists’ way of life, while Thanksgiving traditions are recreated for visitors.

“What the pilgrims are celebrating is literally that they are going to have food. They are not going to starve in the coming year,” says Malka Benjamin, director for colonial interpretation and training at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums. “And so, guests are going to be able to help with cooking preparations for the celebration. They might get pulled into a game, a sport … there’s going to be musket firing demonstrations.”

It was the sounds of guns going off that prompted Native Americans to investigate, which is how her Wampanoag ancestors came to be at the first Thanksgiving, according to Peters.

“At some point, they decided, ‘Oh, this isn’t a threat. They’re just celebrating their harvest.’ And guess what? We’re all here now, so, we’re all going to eat,” says Peters, who used to work at the Plimouth Patuxet Museums.

That part of the story is disputed by Peters’ former colleague, Richard Pickering, chief historian at the living history museum, who says that theory was discussed, but then discarded, by the museum.

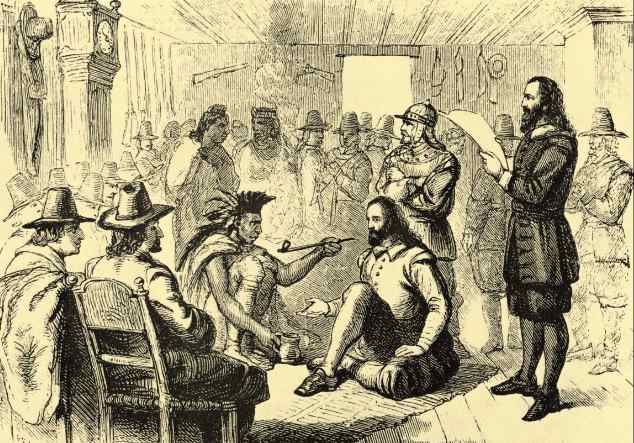

The conflicting viewpoints underscore the reality that no one really knows exactly what happened at the first Thanksgiving. There are almost no firsthand accounts of the event, but there are references to a “special celebration” of the successful harvest, which included Wampanoag leader Massasoit and about 90 of his people, which included women, according to Pickering.

“For three days, we entertained and feasted,” pilgrim Edward Winslow wrote in a letter to a friend in 1621. Winslow attended the harvest celebration.

“Ultimately, what happens in Plymouth in the fall of 1621 is the highest level of diplomacy,” says Pickering, adding that the shared meal was a product of the alliance between the newcomers and the Native people.

“It is their willingness to show them their ways that saves the English that second year. So, we should not be projecting any kind of distrust, animus, on that event. But we should recognize that their children and their grandchildren could not sustain it,” he said.

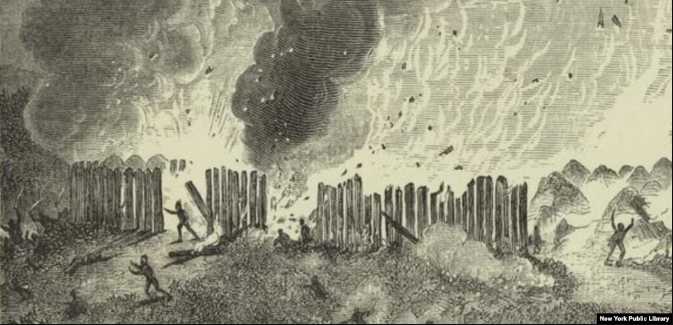

About 90% of the Native population was eventually wiped out by diseases that came with the Europeans. And the respect the pilgrims initially showed the Native people eventually gave way to disdain and dehumanization.

“As the English population grows from those 52 English men, women and children that survived the first winter to the 25,000 or more that are here 20 years later, Native people are seen as being in the way of the commodities that the English want,” Pickering says. “They want their land. They want them off that land. And so, you see a changing attitude from one of admiration to one of stereotyping and derision. And it’s that kind of thought that enables them to want to push them off the land with no sense of guilt.”

The pilgrims originally came to America in search of religious freedom but apparently not for all, says Peters.

“They sacrificed so much for religious freedom, but they didn’t offer that same grace to the Indigenous people who lived here to begin with,” she says.

Harvest meal

Today, Americans often eat traditional Thanksgiving foods that include turkey, stuffing, sweet and mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie. As to what was at the original three-day feast, the museum has a display of the foods that were probably eaten at the 1621 meal.

“You have roast turkey, roast goose, and you’ll see all of the classic corn, beans and squash. There’s maize, beans and squash,” says Pickering, pointing out the foods in a display case. “And also, the standing dish of New England, stewed pumpkin, mussels, to represent all the shellfish that was eaten.”

It’s believed the Wampanoag brought deer they’d hunted.

“And there probably would be some cranberries, because that was the fruit of the season,” Peters says.

Into the future

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe has begun initial proceedings to establish their own living history museum.

The town of Mashpee, located about 43 kilometers from Plymouth, is negotiating the potential transfer of three parcels of land to the tribe for a traditional Wampanoag village and living history museum.

Costa, who oversees the similar effort at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums, is keen for visitors to know that Native Americans shouldn’t be relegated to the past.

“The main thing I want them to learn is that Wampanoag people are still here,” Costa says. “I want them to think of Wampanoag people as not just in the past — or even Indigenous people as in the past — but as in the present still making their way, still teaching the public.”

|

|

|