ANCHORAGE, Alaska-If it weren't for the October scare involving the Salmon Virus, the world would probably never known about the results of work done a decade earlier on the subject. It was the October revelation that the Atlantic Salmon virus had jumped oceans to the Pacific. It was then that we found out that that news is about 10 years too late.

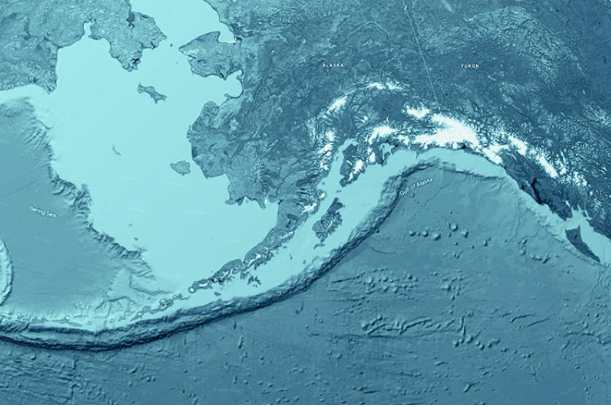

During the period of August 2002 and April of 2003 when a study of Chum, Coho, Pink and Sockeye Salmon was done from the coast of Vancouver Island to the Bering Sea by Canadian researchers. One of the researchers, Molly Kibenge found indications of the virus in 117 fish studied. The studies showed that the wild salmon were all asymptomatic, meaning that they had the virus, but were not detrimentally affected by it.

This reflected the opinion of a paper written a year earlier by Molly’s husband, Fred Kibenge. In that paper Mr. Kibenge concluded that the Salmon Virus in the Atlantic only appeared to harm farmed Salmon and that the virus was present in wild stocks, but that the infection was only mild and seemed not to be harmful to those fish.

But, in October as news broke that the virus was now found on the West Coast, Molly Kibenge attempted to have her paper published, a paper which came to a conclusion that was clearly at-opposition to the Canadian governments conclusion on the virus.

Having her paper published would have opened up her results to peer review, but Simon Jones, of the Animal Health section of the Pacific Biological Station refused. The reason he gave Kibenge for the refusal was, “All attempts to isolate the virus into cell culture failed.” Kibenge knew this, she was aware that even during the huge Chilian outbreak of the virus there that decimated the farmed salmon stocks, isolating the virus into cell culture was difficult at best.

Oddly enough, Molly Kibenge’s paper would have mostly allayed the fears of many, in that it showed that while the virus was present in Pacific Salmon, they seemed to have endured the disease well. This does not rule out the possible incubation of a mutated, more virulent strain of virus in the cramped condition of farms, that could make itself known to wild stocks, where wide-spread decimation could occur.

Alexandra Morton, who found the latest suspect Salmon this fall, wrote a scathing letter to Minister Ashfield, where she said in part, “There is no reason BC would not have been contaminated by ISAv. Your department left the door wide open! You did not include ISAv on the hatchery import forms, likely because no one can actually sign a document saying there is no ISAv in Atlantic salmon eggs – the virus is that widespread. Your department did not even make ISAv a reportable disease in salmon farms, even as the same companies as use BC waters triggered a massive ISAv epidemic in Chile. This is unconscionable.” Her letter, in entirety, can be read here.

So, why would the Canadian government cover up the fact that there was a paper on the subject of the Salmon virus in the Pacific? The main reason would be that if the presence of the virus was confirmed in the West Coast waters, the Canadian government would have no choice to report that presence to the World Organization for Animal Health. Reporting this information would be devastating to Canada’s Aquaculture industry.

The cover up of the information was so complete that even the top fish virologist across the border in Washington, Jim Winton had no knowledge that a paper even existed. He said, “No one ever revealed that there was a publication that was ready to go to a journal or that the data were as compelling as they appear to be. This is puzzling and very frustrating. It’s unfortunate that this information was not available sooner. This should have been followed up years ago.”

Alaska’s top fish pathologist, Ted Meyers is of a similar opinion, and believes that politicians got in the way.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada released a statement saying that the paper’s finding were in error and that Kibenge’s results were a false positive.

Winton diagrees, and says that in order to get a false positive on all samples, all samples would have to have been contaminated, a scenario that Winton believes unlikely, he said, “The Canadian response is less than satisfactory, it seems inadequate to the occasion.”