[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 1908, a colossal blast incinerated a swath of wilderness deep in Siberia, at about the same latitude as Anchorage.

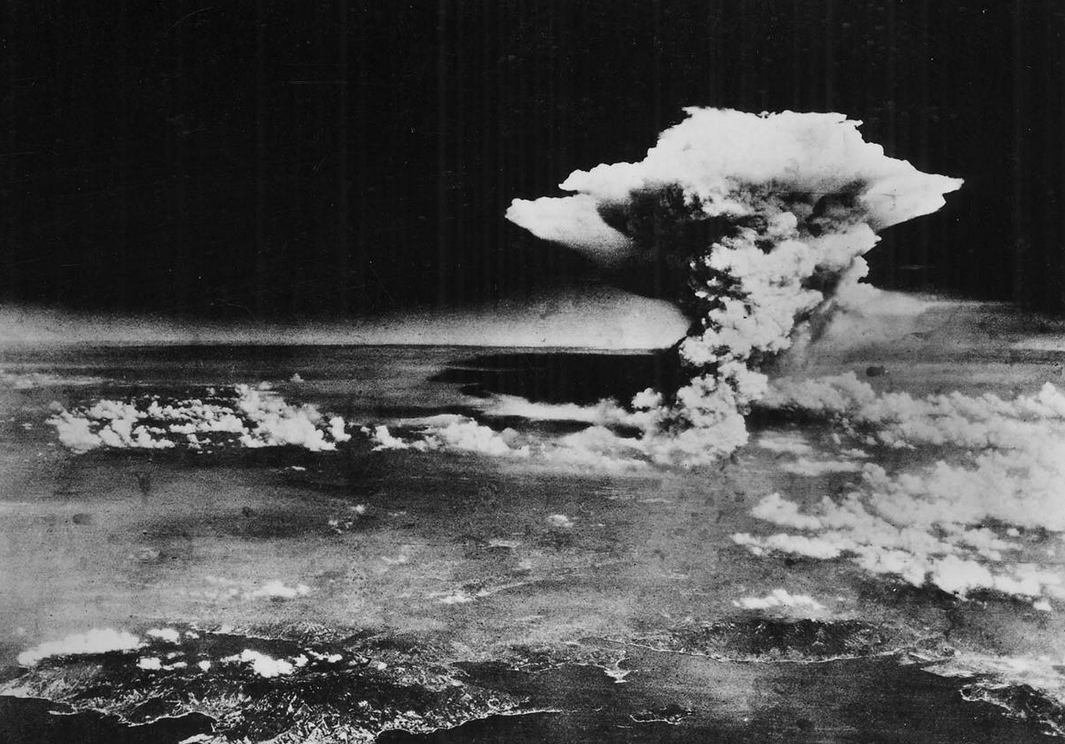

The explosion that July day registered on seismic recorders all over the world. Within minutes, 80 million trees lay flat and scorched in a circle 60 miles wide. Scientists calculated the shock was more than 1,000 times stronger than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

What happened? That’s a great question. Nineteen years after the event and 91 years ago, Leonid Kulik, curator for the meteorite collection at the St. Petersburg Museum, traveled to the Stony Tunguska River to find out. From the distant evidence, he expected to see a crater where a meteorite crashed into Earth.

He found none. Those that have followed him over the years have not found expected nickel or iron deposits. Nor have they collected any space rocks like those fired into the snow when the Chelyabinsk meteorite exploded above the Ural Mountains in 2013.

If the Tunguska event was not from a heavenly body crashing into or exploding just above Earth, what was it?

[content id=”79272″]

Gunther Kletetschka last visited the site in summer 2018 trying to find out. A specialist on Earth’s magnetism and meteorite impacts affiliated with Charles University in Prague, Kletetschka is now doing work with UAF’s Geophysical Institute. He gave a recent talk about his travel to Siberia.

At the Tunguska blast site, Kletetschka hiked to a few Siberian larch trees that remained standing after the 1908 blast. The shock waves killed most trees, but a few took the hit and remained upright, maybe because pressure waves came straight down upon them instead of at an angle.

At the site, Kletetschka cored two standing trees that survived the blast and the years after it. One was 14 years old in 1908, the other 131. Back in a lab, he analyzed the wood samples using X-ray fluorescence.

He saw levels of calcium usually present only in the bark of living trees was deep in the center of the blast survivors. He concluded that pressure waves may have pushed tree fluids from the living phloem layer near the bark into the dead wood of the interior.

What does that mean? Kletetschka is not sure. No one else is, either. Was the blast that leveled the Stony Tunguska River hills from a comet whose ice soon disappeared? Did a pingo explode? Was dark matter expressing its mysterious energy in a violent way after interacting with Earth?

“We still don’t know what happened,” Kletetschka said.

Alaska has felt the colossal smack of comets and meteorites a few hundred times. Almost all of their indentations are buried and hidden from view.

One of them is Avak impact crater near Utqiaġvik. Millions of years ago, a meteorite or comet the diameter of downtown Fairbanks crashed into the shallow ocean that covered northern Alaska. It left behind a steaming crater six miles from rim to rim.

Geologists Florence Weber and Florence Collins discovered Avak in the 1950s. Looking at samples from the Naval Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, they noticed shattered and tilted rock samples. The blast that created Avak impact crater busted up the rock to make folds that trapped natural gas. Navy researchers later tapped into the gas supply to heat buildings in the research station near Utqiaġvik, formerly Barrow. In 1964, they enabled gas distribution to the village. The North Slope Borough took over the natural gas operation in the 1980s, supplying Utqiaġvik residents with a local source of energy.

Source: Geophysical Institute