Credit: Harris County, Texas

Ozone and heat

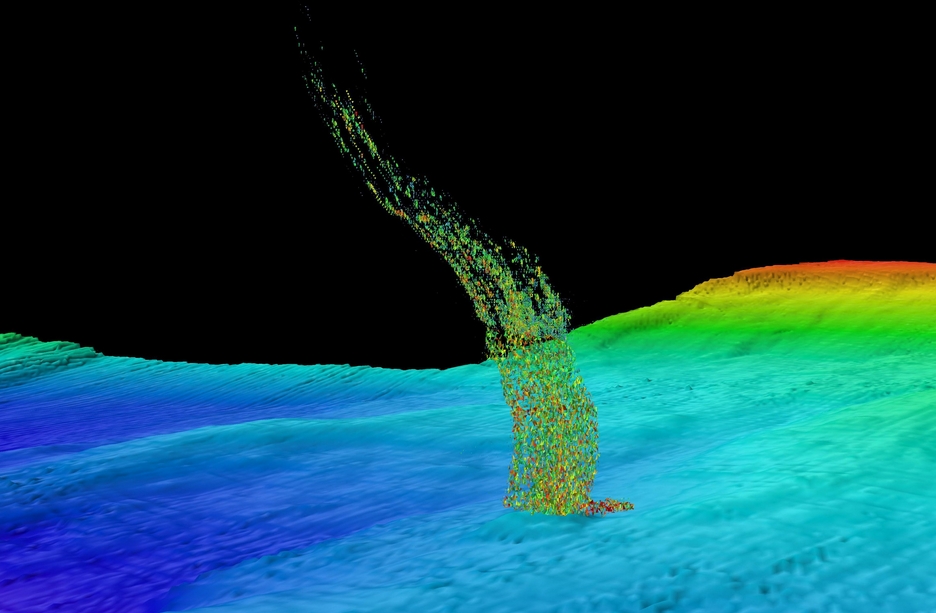

Ozone pollution is not emitted directly. It forms as a result of chemical reactions that take place between nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds in the presence of sunlight.

These gases come from human activities such as combustion of coal and oil, as well as natural sources such as emissions from plants.

To examine the effects of climate change on ozone pollution, Pfister and colleagues looked at two scenarios.

In one, emissions of nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds from human activities would continue at current levels through 2050.

In the other, emissions would be cut by 60-70 percent. Both scenarios assumed continued greenhouse gas emissions with significant warming.

The researchers found that, if emissions continue at present-day rates, the number of eight-hour periods in which ozone would exceed 75 parts per billion (ppb) would jump by 70 percent on average across the United States by 2050.

The 75 ppb level over eight hours is the threshold that is considered unhealthy by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (The agency is considering tightening the standard to a value between 65 and 70 ppb over eight hours.)

Overall, the study found that, 90 percent of the time, ozone levels would range from 30 to 87 ppb in 2050 compared with an estimated 31 to 79 ppb at present.

Although the range itself shifts only slightly, the result is a much larger number of days above the threshold considered unhealthy.

There are three primary reasons for the increase in ozone with climate change:

- Chemical reactions in the atmosphere that produce ozone occur more rapidly at higher temperatures.

- Plants emit more volatile organic compounds at higher temperatures, which can increase ozone formation if mixed with pollutants from human sources.

- Methane, which is increasing in the atmosphere, contributes to increased ozone globally and will enhance baseline levels of surface ozone across the United States.

In the second scenario, Pfister and colleagues found that sharp reductions in nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds could reduce ozone pollution even as the climate warms.

In fact, 90 percent of the time, ozone levels would range from 27 to 55 ppb.

The number of instances when ozone pollution would exceed the 75 ppb level dropped to less than 1 percent of current cases.

“Our work confirms that reducing emissions of ozone precursors would have an enormous effect on the air we all breathe,” Pfister said.

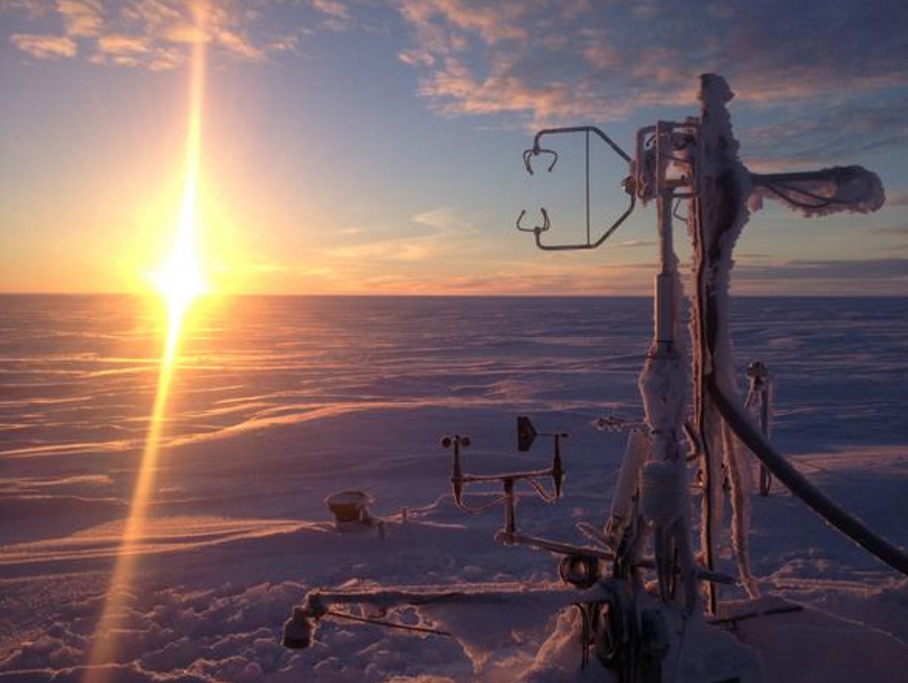

Pfister and a nationwide scientific team expect to learn more about the sources, chemistry and movement of air pollutants this summer when they launch a major field experiment known as FRAPPÉ along Colorado’s Front Range.