MADISON – The oceans teemed with life 600 million years ago, but the simple, soft-bodied creatures would have been hardly recognizable as the ancestors of nearly all animals on Earth today.

Then something happened. Over several tens of millions of years – a relative blink of an eye in geologic terms – a burst of evolution led to a flurry of diversification and increasing complexity, including the expansion of multicellular organisms and the appearance of the first shells and skeletons.

The results of this Cambrian explosion are well documented in the fossil record, but its cause – why and when it happened, and perhaps why nothing similar has happened since – has been a mystery.

New research shows that the answer may lie in a second geological curiosity – a dramatic boundary, known as the Great Unconformity, between ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks and younger sediments.

“The Great Unconformity is a very prominent geomorphic surface and there’s nothing else like it in the entire rock record,” says Shanan Peters, a geoscience professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who led the new work. Occurring worldwide, the Great Unconformity juxtaposes old rocks, formed billions of years ago deep within the Earth’s crust, with relatively young Cambrian sedimentary rock formed from deposits left by shallow ancient seas that covered the continents just a half billion years ago.

Named in 1869 by explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell during the first documented trip through the Grand Canyon, the Great Unconformity has posed a longstanding puzzle and has been viewed – by Charles Darwin, among others – as a huge gap in the rock record and in our understanding of the Earth’s history.

But Peters says the gap itself – the missing time in the geologic record – may hold the key to understanding what happened.

In the April 19 issue of the journal Nature, he and colleague Robert Gaines of Pomona College report that the same geological forces that formed the Great Unconformity may have also provided the impetus for the burst of biodiversity during the early Cambrian.

“The magnitude of the unconformity is without rival in the rock record,” Gaines says. “When we pieced that together, we realized that its formation must have had profound implications for ocean chemistry at the time when complex life was just proliferating.”

“We’re proposing a triggering mechanism for the Cambrian explosion,” says Peters. “Our hypothesis is that biomineralization evolved as a biogeochemical response to an increased influx of continental weathering products during the last stages in the formation of the Great Unconformity.”

Peters and Gaines looked at data from more than 20,000 rock samples from across North America and found multiple clues, such as unusual mineral deposits with distinct geochemistry, that point to a link between the physical, chemical, and biological effects.

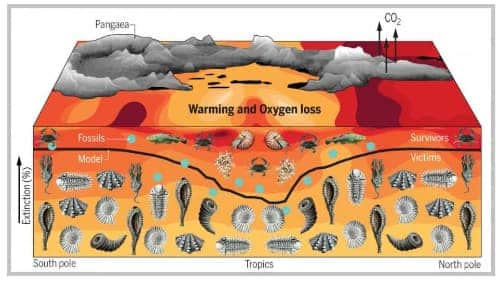

During the early Cambrian, shallow seas repeatedly advanced and retreated across the North American continent, gradually eroding away surface rock to uncover fresh basement rock from within the crust. Exposed to the surface environment for the first time, those crustal rocks reacted with air and water in a chemical weathering process that released ions such as calcium, iron, potassium, and silica into the oceans, changing the seawater chemistry.

The basement rocks were later covered with sedimentary deposits from those Cambrian seas, creating the boundary now recognized as the Great Unconformity.

Evidence of changes in the seawater chemistry is captured in the rock record by high rates of carbonate mineral formation early in the Cambrian, as well as the occurrence of extensive beds of glauconite, a potassium-, silica-, and iron-rich mineral that is much rarer today.

The influx of ions to the oceans also likely posed a challenge to the organisms living there. “Your body has to keep a balance of these ions in order to function properly,” Peters explains. “If you have too much of one you have to get rid of it, and one way to get rid of it is to make a mineral.”

The fossil record shows that the three major biominerals – calcium phosphate, now found in bones and teeth; calcium carbonate, in invertebrate shells; and silicon dioxide, in radiolarians – appeared more or less simultaneously around this time and in a diverse array of distantly related organisms.

The time lag between the first appearance of animals and their subsequent acquisition of biominerals in the Cambrian is notable, Peters says. “It’s likely biomineralization didn’t evolve for something, it evolved in response to something – in this case, changing seawater chemistry during the formation of the Great Unconformity. Then once that happened, evolution took it in another direction.” Today those biominerals play essential roles as varied as protection (shells and spines), stability (bones), and predation (teeth and claws).

Together, the results suggest that the formation of the Great Unconformity may have triggered the Cambrian explosion.

“This feature explains a lot of lingering questions in different arenas, including the odd occurrences of many types of sedimentary rocks and a very remarkable style of fossil preservation. And we can’t help but think this was very influential for early developing life at the time,” Gaines says.

Far from being a lack of information, as Darwin thought, the gaps in the rock record may actually record the mechanism as to why the Cambrian explosion occurred in the first place, Peters says.

“The French composer Claude Debussy said, ‘Music is the space between the notes.’ I think that is the case here,” he says. “The gaps can have more information, in some ways, about the processes driving Earth system change, than the rocks do. It’s both together that give the whole picture.”

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Source: University of Wisconsin-Madison