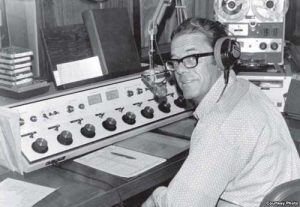

WASHINGTON — Elsie Boudreau was 10 years old that afternoon in 1978 when Father James Poole called her and two playmates into the office of a small radio station he had founded in Nome, Alaska.

“He had us line up against the wall and began asking us questions,” said Boudreau, who grew up in St. Mary’s, a tiny Yup’ik village in northwest Alaska where Poole had earlier served as pastor. “Then, he told the two other girls that they could leave, but that I should stay. He said it was because I was so much more mature than the other girls.”

The abuse began with hours of French kissing and later escalated, lasting nine years.

“I have a memory of him being on top of me in a super high bed,” Boudreau said. “I must have had an out-of-body experience, because when I look back, I’m actually hiding behind a door, peeking out, seeing myself in bed with him, a little girl with long hair in braids.”

In 2003, Boudreau took action and wrote to the bishop of Alaska at the Fairbanks diocese. Unhappy with his response, she sued the Catholic Church and the Society of Jesus. She reached a $1 million settlement in 2005.

At the time of publication, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops had not responded to VOA’s request for comment.

Legal barriers

For Barbara Charbonneau-Dahlen, justice remains elusive.

At the age of 5, Charbonneau-Dahlen, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota, was sent to the St. Paul’s Indian Mission School, a boarding school on the Yankton Sioux Reservation in Marty, South Dakota, where she said she and her nine sisters suffered horrific abuse.

“Father Francis took me to the church basement where they stored coffins when somebody died,” she said. “He would lift me up and tell me that if I didn’t do what he told me to, he would put me in a coffin.”

She said he forced her to perform oral sex on him and knows of other girls who became pregnant.

“They aborted the babies right there at the school,” she said, “and burned the fetuses in the incinerator. I worked in the incinerator room, and anything Sister brought down in that bucket, I just had to put it in the incinerator.”

She added, weeping openly: “When I look back, I wonder if I had to burn any fetuses.”

Charbonneau-Dahlen and her sisters were among dozens who filed lawsuits in the early 2000s against two Catholic dioceses and several religious orders for abuse that occurred at two Indian schools over four decades.

The South Dakota Supreme Court dismissed their claims, ruling that the statute of limitations had long run out. The state has one of the toughest statutes of limitations in the U.S.: No one under age 40 can sue — and they may only sue the actual abuser, not religious institutions.

Today, Barbara Charbonneau-Dahlen and her sisters range in age from their 60s to 80s. Their lawyer, Michelle Dauphinais Echols, has authored legislation that would eliminate the statute of limitations in certain child sex abuse cases. But in February, South Dakota senators turned it down. Echols said she plans to reintroduce the bill in early 2019.[content id=”79272″]

Charbonneau-Dahlen said she isn’t holding out hope. “We’re just forgotten. They’ll drag it out till we’re all old and dead.”

Untold numbers

BishopAccountability.org, a massive online database of clergy abuse cases, details hundreds of cases in which the church covered up accusations of abuse by sending problem priests elsewhere.

“The church would send known offenders to Native American communities because they knew that people would not speak up,” said Patrick J. Wall, a former Benedictine priest who once helped the Church “fix” cases of priest abuse. He was a consultant to Boudreau’s lawyer in the Alaska case.

“The Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, knew about the problems with Father James Poole as early as 1960. They never called the police. All they did is move him down to the Lower 48 [states] for a year or two, and then they allowed him to come back to Alaska and continue abusing for another 25 years.”

There is no way to know how many Native American-Alaska Native children have been victimized, said Vito de la Cruz, a Yaqui-Chicano attorney in Washington state who represents Native American abuse survivors.

“Just to give you an idea, in Montana, we sued both the Helena and Great Falls-Billings dioceses. At the end of the day, the number of survivors who came forward to be part of those lawsuits exceeded 450 to 500 people,” de la Cruz said.

The emotional impact on survivors is devastating.

“On the reservation, you have cross-generational trauma as a result of a systematic effort to either eliminate Native communities or diminish them by stripping them of land, rights and sovereignty,” he said. “We are conquered people, and when you add this layer of abuse on top of it, you add a layer of cross-generational emotional and psychological trauma.”

That trauma, research shows, is to blame for high rates of alcoholism, drug abuse and suicide in Native American communities.

As part of the U.S. federal government’s policy of assimilation of Native Americans, thousands of children were forced to attend boarding schools, many of them run by the Catholic Church.

Today, all of the Catholic boarding schools have closed or are owned and operated by tribes or the U.S. government.

Source: VOA