Each year, more than 10 million girls under the age of 18 marry, usually under force of local tradition and social custom. Almost half of these compulsory marriages occur in South Asia. A new study suggests that more than two decades of effort to eliminate the practice has produced mixed results.

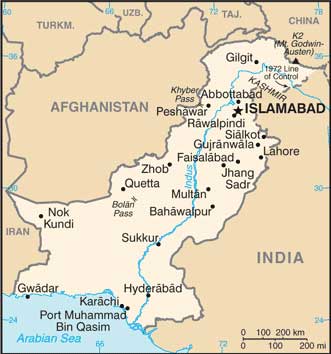

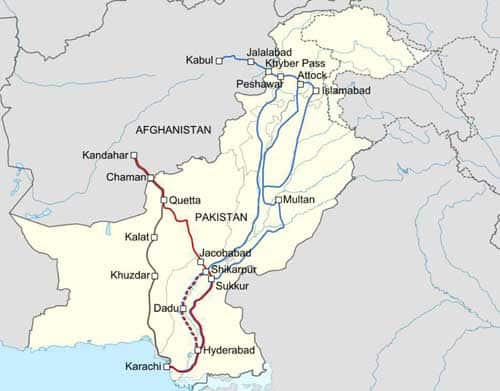

Writing in the May 16, 2012 issue of Journal of the American Medical Association, Anita Raj, PhD, professor of medicine in the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, and colleagues, report that marriage rates for girls under the age of 14 in India, Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh – the South Asian countries with the highest historical rates – have significantly declined since 1991. Conversely, the rate among girls aged 16 and 17 continues largely unchanged or, in the case of Bangladesh, has increased 36 percent.

Childhood marriage, which mostly involves girls, is widely condemned as a violation of individual human rights. Numerous studies have found that child brides are more likely to die young, suffer from serious health problems, live in poverty and remain illiterate.

“There is a global effort to eliminate girl child marriage,” said Raj. “Our findings are heartening in terms of eliminating the practice among very young girls, but not among older girls. There needs to be a greater focus on prevention of marriage among later adolescents. If we cannot impact reduction of marriage in this age group, we’ll continue to see inadequate change on reduction of girl child marriage as a whole.”

Raj and colleagues examined randomized cluster samples from multiple demographic, health and nutrition surveys taken between 1991 and 2007 in India, Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh, where the prevalence of girl child marriages has historically reached or exceeded 20 percent.

They found that the marriage prevalence rate for girls under age 14 decreased across the board during the time span studied: 45 percent in Bangladesh, 35 percent in India, 57 percent in Nepal and 61 percent in Pakistan. Reductions in other age groups, however, were less promising. Marriage of 16- and 17-year-old girls showed no decline over the past 20 years for any of the South Asian countries assessed; Bangladesh actually demonstrated a 36 percent increase in marriage of girls within this age group. Raj said Bangladesh’s significant increase in marriages among 16- and 17-year-old girls probably reflected a shift from younger aged groups.

The factors influencing reduction in childhood marriage rates remain imperfectly understood. For example, Raj noted that the laws governing legal marriage age are not the same for the four countries studied. “Pakistan has a legal age of 16 for marriage while in India, it is 18,” she said, “but the percentage of females married as minors is greater for India than Pakistan, so we do not feel law has as much impact as social norms.”

More influential, perhaps, is the role of education, which Raj and colleagues are now studying. “There have been rigorous evaluations of interventions in Ethiopia and Malawi aimed at retaining girls in schools, with the result of delayed age at marriage. We need better understanding of the degree to which girl education can reduce risk for early marriage among girls in South Asia.”

Co-authors are Lotus McDougal, Joint Doctoral Program, UC San Diego-San Diego State University and Melanie L. A. Rusch, PhD, Division of Global Public Health, UC San Diego School of Medicine.

Funding for this research came, in part, from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Source: UC San Diego Health System