Team works independently and in partnership with NOAA Fisheries.

For Native American Heritage Month, NOAA Fisheries celebrates the Indigenous scientists who help make our work in marine mammal conservation possible. The Tribal Government of the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island conducts high-level science and management of their marine resources. They work independently and in partnership with NOAA through a formal co-management agreement authorized by the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

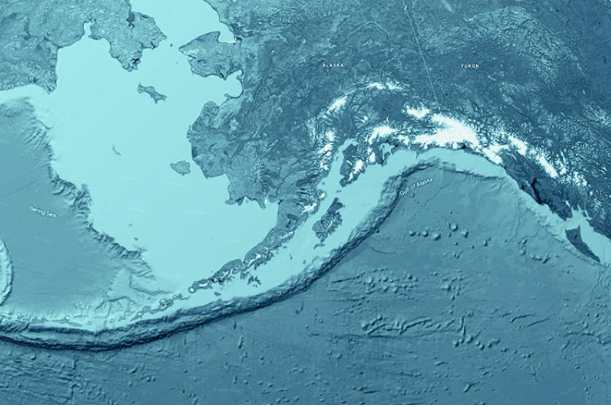

St. Paul is a small community of about 400 people located in the Pribilof Islands, 300 miles from mainland Alaska in the Bering Sea. Unangan—which means “The People of the Sea”— live on St. Paul, and neighboring St. George. Russian fur traders captured their ancestors from the Aleutian Islands and relocated them to the Pribilof Islands in the 1700s. They were enslaved there for the commercial fur harvest of laaqudan (the Unangam tunuu word for northern fur seals, pronounced “lah-koo-thawn”). Their deep cultural connection to and subsistence reliance upon laaqudan and other marine mammals, such as qawan (Steller sea lions, “ka-wahn”), has persisted for millennia and remains strong to this day.

Giving Laaqudan a Fighting Chance

The Tribal Government’s Ecosystem Conservation Office is dedicated to the conservation and stewardship of the vital marine resources upon which Unangan culture and subsistence depends. One ongoing aspect of their work is the disentanglement of laaqudan from marine debris. Laaqudan entangled in debris—such as packing bands and fishing net fragments— have been observed in the Pribilofs since the 1930s. Due to the islands’ location in the central Bering Sea and local current patterns, a great deal of marine debris accumulates both in the waters surrounding and on the Pribilof Islands. Animals may become entangled either near the islands during breeding season, or during their winter or spring migrations. Entanglement greatly reduces a fur seal’s chance of survival. It can restrict movement or cause injury as debris cuts into the skin over time, particularly for young animals that continue to grow after becoming entangled.

The Tribe’s disentanglement program began in 2000, but Tribal members have been involved in capturing and disentangling fur seals since the commercial harvest of fur seals ended on St. Paul in 1984. Three key members of the Entanglement Program team are Paul Melovidov, Dallas Roberts, and Aaron Lestenkof, all of whom are Unangan scientists born and raised on St. Paul. They disentangled 46 laaqudan in 2022 and 52 in 2023.

“Our current understanding of fur seal entanglement would be significantly lacking without the initiatives and efforts taken by the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island over the past 30 years—not to mention the good they have done for the hundreds of seals that have been disentangled,” said Mike Williams, Pribilof Islands Program manager for NOAA Fisheries.

Disentanglement work is highly technical, physical, and can be dangerous, and therefore should be left to trained, experienced, and authorized personnel. Laaqudan are very social and tend to gather in large groups when on land. This can make it difficult to isolate and capture an individual entangled animal to remove the debris. The Ecosystem Conservation Office conducts near-daily surveys for entangled animals in summer and fall.

If the team spots one, they assess the situation from a distance, then approach cautiously to avoid disturbing the herd for as long as possible. Once close enough to be noticed, they often have to race to stop the entangled individual from escaping to the sea. Part of this race includes assessing the laaqudan’s potential escape route. They also have to determine the best and safest way to respond while avoiding dozens, if not hundreds, of large subadult males bolting towards the ocean. It is a dangerous game of leapfrog that the team does not take lightly.

Once close enough, the team captures the entangled seal with a net or by looping long “noose poles” with a U-shaped rope at the end around its neck, taking care not to hurt it or restrict its breathing. Laaqudan have extremely sharp teeth and are very strong. For everyone’s safety, one or more people restrain the animal’s head while somebody else cuts and frees the debris. When possible, they tag its flipper to allow for future monitoring of its health and survival.

Once the response is complete and the laaqudan is released, Aaron, Paul, Dallas and their team never know for sure if it will survive, particularly if it has been entangled long or has deep wounds. However, their work gives these laaqudan a fighting chance, whereas remaining entangled is usually an eventual death sentence.