WASHINGTON — Lakota from reservations across South Dakota gathered at the Wounded Knee Cemetery on the Pine Ridge Reservation to commemorate ancestors massacred by the U.S. Cavalry in 1890.

On top of 2-foot snowdrifts at the cemetery on December 29, 2022, lay a collection of cardboard boxes containing artifacts and items of clothing believed to have been ripped from the victims’ bodies. After years of negotiations, the items were returned to the Lakota by a small museum in Barre, Massachusetts.

Museum records show only that a traveling shoe salesman from Barre acquired the items on a trip West in 1891 and donated them to the Barre Museum a few years later.

Now on the cold December day, spiritual leaders Richard Moves Camp, an Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge, and Ivan Looking Horse, a Miniconjou from the Cheyenne River Reservation, led the gathering in prayer and a ritual feeding of the spirits.

Later, dozens of Lakota gathered in the warmth of a nearby school where they shared family histories of the massacre, viewed photos of the returned artifacts, and honored the dead.

VOA spent weeks digging through historic records and newspaper accounts to find out more.

Background

In the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, the U.S. government set aside 233,000 square kilometers west of the Missouri River for the “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota tribes, collectively known as the Sioux.

When Lieutenant General George Custer and his 7th Cavalry confirmed there was gold in the Black Hills of that area, prospectors rushed in. By 1875, the Bureau of Indian Affairs ordered the tribes to move. When they resisted, the U.S. government sent in troops, setting off armed conflict that would see Custer defeated.

By 1889, the various bands of Lakota were consigned to separate reservations, with their old ways of life forbidden and the buffalo, which had sustained them for thousands of years, gone.

Subsisting on inadequate government rations of beef, they looked for a miracle.

The ghost dance

In 1890, the Lakota heard about a Paiute man in Nevada who had a vision while cutting wood for his white employer. He fell and died, and God lifted him to heaven. There, he saw white and Native people, made young again, “dancing, gambling, playing ball and having all kinds of sports.”

That vision sparked the Ghost Dance, based on beliefs that if men were good, worked hard, didn’t fight and danced for five nights in succession, God would bring the dead back to life and restore to the Indians their former ways of life. White men would vanish, but details weren’t clear.

To learn more, the Lakota sent Miniconjou chief Kicking Bear and a Sicangu Lakota from The Rosebud Agency named Short Bull to Nevada.

“They didn’t all speak English,” said Ernie LaPointe, the closest living direct descendant of Chief Sitting Bull. “So, they had to speak with hand signals.”

The message that the duo brought back from Nevada lost something in the translation.

“They told the Indians that they had been up near Salt Lake, Utah, to visit the new Messiah,” U.S. agent at Pine Ridge Daniel Royer telegrammed Washington, “and they were told by him … that a new Earth would be formed and would pass over this one, burying the whites beneath.”

“It was Kicking Bear and Short Bull who conjured up this story that if Indians wore these ghost shirts, that a white man’s bullets would never hurt them,” said LaPointe. He believes the men got the idea from Mormon colonists in Nevada, who wore white “temple garments” to protect them against temptation and spiritual evil.

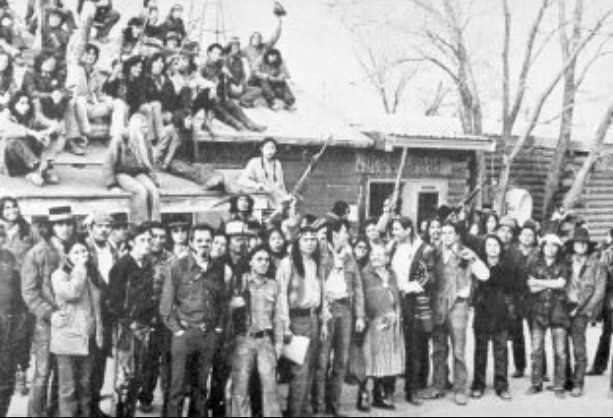

Within weeks, hundreds gathered to dance. Some Indian agents and military officials viewed it as a harmless diversion; others believed the tribes were gearing up for insurrection.

Royer again telegrammed Washington: “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy. … We need protection, and we need it now.”

The White House answered by sending in several thousand troops.

Tipping point

Indian agent James McLaughlin believed Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull was “the high priest” and chief instigator of the “Messiah craze.” He visited Sitting Bull at his cabin near the Grand River and asked him to stop the “absurd craze.” Sitting Bull refused.

“My great grandfather knew that his ghost dance was not a Lakota sacred ceremony. But he had to give his hope to his people, so he allowed them to do this,” LaPointe said.

Sitting Bull decided to violate a travel ban and go to Pine Ridge to confer with Chief Red Cloud about easing tensions.

McLaughlin sent tribal police to arrest Sitting Bull on December 16. In the melee that ensued, Sitting Bull was shot dead.

A massacre

Sitting Bull’s half-brother Hupah Gleska, more commonly known as Si Tanka (“Big Foot”), leader of the Miniconjou Lakota, was at the time camped at the Cheyenne River Agency, 160 kilometers to the north.

“He thought the government was going to come after him,” said Michael He Crow, an Oglala Lakota and descendant of Big Foot. “He felt that he was going to be the next one to die because he had a lot of influence among the people there.”

Big Foot and several hundred followers set out for Pine Ridge, but the Army intercepted them and forced them to camp at the tiny village of Wounded Knee.

On December 29, the Army ordered the Lakota to disarm.

“The men and women were separated,” said He Crow. “Most of the men were sitting in a council circle and were the first ones killed. And the ones running were mostly women.”

What happened to spark the massacre that followed? Some say it was when the medicine man, Yellow Bird, grabbed a handful of dirt from the ground and threw it up into the air.

“He was praying and crying,” a Hohwoju Lakota survivor named Alice Ghost Horse/Kills the Enemy/War Bonnet would later tell her son. “He was saying to the eagles that he wanted to die instead of his people. … He picked up some dirt from the fireplace and threw it in the air and said this is the way he wanted to go back … to dust.”

Others tell a different story.

“When they were taking the guns away from them, there was a man that was deaf,” He Crow said. “They were trying to tell him to put his gun in the middle of the pile, but he held on to the gun and told them, ‘This is the only thing I have to keep food on the table and stay alive. And you’re taking this away from me?’”

The gun went off as officers tried to wrestle it away, said He Crow. And that’s when the Army began firing revolving cannons and rifles.

“It was chaos,” Violet Catches, a Hohwoju Lakota from the Cheyenne River Reservation, said. Her grandfather Leon Holy, then around 12, was one of five children who survived the massacre.

As many as 300 Lakota men, women and children died that day; some who were tracked as far as 3 kilometers from the site. Official accounts say the massacre took 20 minutes, but Ghost Horse/Kills the Enemy/War Bonnet said the shooting didn’t stop until after sunset.

They would be buried in a mass pit several days later, but not before they were picked clean of their weapons and belongings, including the ghost shirts on their backs.

NOTE: Part 2 of this story will examine the “relics craze” that followed the massacre and show how dozens of items associated with Wounded Knee ended up in Massachusetts.

[content id=”52927″][content id=”79272″]