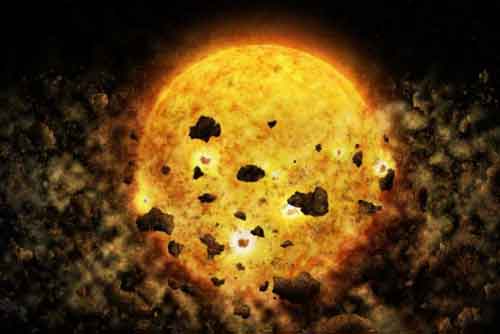

Scientists from the University of Leeds have discovered enough water vapour to fill Earth’s oceans more than 2000 times over in a gas and dust cloud which is about to collapse into a Sun-like star.

The research, led by Professor Paola Caselli, is the first detection of water vapour in a ‘pre-stellar core’, the cold, dark clouds of gas and dust from which stars form.

“To produce that amount of vapour, there must be a lot of water ice in the cloud, more than three million frozen Earth oceans’ worth,” says Professor Caselli, the lead author of the paper published in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The discovery was made using the European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Observatory, in a pre-stellar core known as Lynds 1544, in the constellation of Taurus.

Water has previously been detected outside of our Solar System as gas and ice coated onto tiny dust grains near sites of active star formation, and in proto-planetary discs capable of forming planetary systems.

More than 2000 Earth oceans-worth of water vapour were detected, liberated from icy dust grains by high-energy cosmic rays passing through the cloud.

“Before our observations, the understanding was that all the water was frozen onto dust grains because it was too cold to be in the gas phase and so we could not measure it.

“Now we will need to review our understanding of the chemical processes in this dense region and, in particular, the importance of cosmic rays to maintain some amount of water vapour.”

The research also revealed that water molecules are flowing towards the heart of the cloud where a new star is likely to form, indicating that gravitational collapse has just started.

“There is absolutely no sign of stars in this dark cloud today, but by looking at the water molecules, we can see evidence of motion inside the region that can be understood as collapse of the whole cloud towards the centre,” says Professor Caselli.

“There is enough material to form a star at least as massive as our Sun, which means it could also be forming a planetary system, possibly one like ours.”

Some of the water vapour detected in L1544 will go into forming the star, but the rest will be incorporated into the surrounding disc, providing a rich water reservoir to feed potential new planets.

“Thanks to Herschel, we can now follow the ‘water trail’ from a molecular cloud in the interstellar medium, through the star formation process, to a planet like Earth where water is a crucial ingredient for life,” says ESA’s Herschel project scientist, Göran Pilbratt.