The loss of glaciers worldwide enhances the breakdown of complex carbon molecules in rivers, potentially contributing further to climate change.

University of Alaska Southeast Professor of Environmental Science Eran Hood was part of an international research team led by the University of Leeds that has for the first time linked glacier-fed mountain rivers with higher rates of plant material decomposition, a major process in the global carbon cycle.

As mountain glaciers melt, water is channeled into rivers downstream. But with climate change accelerating the loss of glaciers, rivers have warmer water temperatures and are less prone to variable water flow and sediment movement. These conditions are then much more favorable for fungi to establish and grow.

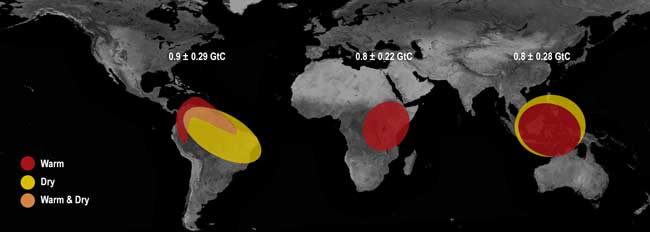

Fungi living in these rivers decompose organic matter such as plant leaves and wood, eventually leading to the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The process – a key part of global river carbon cycling – was measured in 57 glacial rivers in six mountain ranges across the world, in Austria, Ecuador, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United States.

The findings, funded mainly by the Natural Environment Research Council, were published in the journal Nature Climate Change this week.

“This study demonstrates a new link between glacier loss and climate change, namely that as glaciers shrink and contribute less to streamflow the rate of carbon cycling in rivers will increase and release more carbon (as CO2) to the atmosphere. Moreover, the patterns we detected were coherent across glacial rivers on four continents showing that this is a global phenomenon,” said Hood. Hood contributed research from Southeast Alaska watersheds, supported by funding from the Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center.

“This is an unexpected form of climate feedback, whereby warming drives glacier loss, which in turn rapidly recycles carbon in rivers before it is returned to the atmosphere, “ said lead author Sarah Fell, of Leeds’ School of Geography and water@leeds.[content id=”79272″]

The retreat of mountain glaciers is accelerating at an unprecedented rate in many parts of the world, with climate change predicted to drive continued ice loss throughout the 21st century.

However, the response of river ecosystem processes (such as nutrient and carbon cycling) to decreasing glacier cover, and the role of fungal biodiversity in driving these, remains poorly understood.

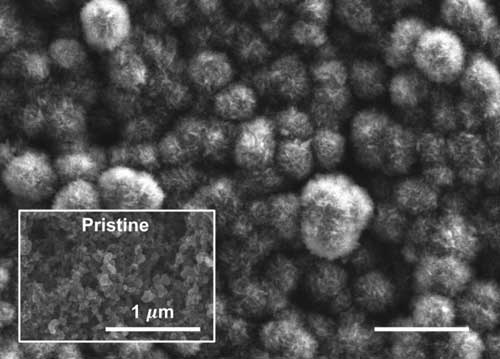

The research team used artists’ canvas fabric to mimic plant materials such as leaves and grass that accumulate naturally in rivers. This was possible because the canvas is made from cotton, predominantly composed of a compound called cellulose – the world’s most abundant organic polymer which is found in plant leaves that accumulate in rivers naturally.

The canvas strips were left in the rivers for approximately one month, then retrieved and tested to determine how easily they could be ripped. The strips ripped more easily as aquatic fungi colonized them, showing that decomposition of the carbon molecules proceeded more quickly in rivers that were warmer because they had less water flowing from glaciers.

As algal and plant growth in glacier-fed rivers is minimized by low water temperature, unstable channels, and high levels of fine sediment, plant matter breakdown can be an important fuel source to these aquatic ecosystems. In some parts of the world, such as Alaska and New Zealand, glacier-fed rivers also extend into forests that provide greater amounts of leaf litter to river food chains.

The study’s co-author, Professor Lee Brown, also of Leeds’ School of Geography and water@leeds, explained: “Our finding of similar patterns of cellulose breakdown at sites all around the world is really exciting because it suggests that there might be a universal rule for how these river ecosystems will develop as mountains continue to lose ice. If so, we will be in much-improved position to make forecasts about how river ecosystems will change in future.”

Learn more about Alaska Coastal Rainforest Center research at acrc.alaska.edu.

###