WASHINGTON — Each year on the last Thursday of November, families in the United States gather to celebrate Thanksgiving. It was originally intended as a day of prayer and gratitude — not just for good harvests but for a leader’s good health or success in battle.

Today, the holiday revolves around a sentimentalized retelling of the 1620 landing of Puritan refugees at Plymouth, Massachusetts, and the harvest feast they shared with local Wampanoags.

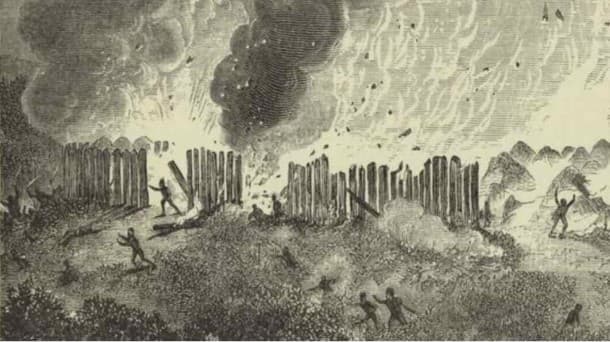

That version omits the fact that 17 years later, Puritans would set fire to a fortified Pequot village, burning men, women and children alive.

Today, Native Americans regard Thanksgiving with mixed emotions.

“Native Americans eat and watch football just like other Americans,” said Shawna Shale, a Quinault woman living in Fergus Falls, Minnesota. “But for some, it is a reminder of a dark past that is hard to celebrate.”

She admits that she often wonders how differently life would have turned out if the Wampanoag tribe decided not to ally itself with the Plymouth pilgrims.

Thanksgiving memories

Many Native Americans never heard of Thanksgiving until they were sent to boarding school.

“[I am] a second-generation turkey eater, after my parents,” said artist Roberta Begay, a Diné (Navajo) citizen living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “It’s a boarding school tradition. I never understood it as anything other than a time for a family gathering, eating and helping my grandparents by hauling water or going out for firewood.”

Phoenix, Arizona, resident Reva Stewart, also Diné, experienced her first Thanksgiving in a Christian boarding school. She was 4 years old.

“We were given Thanksgiving dinner with the idea that we should be grateful that we were saved,” she said. “Today, my family celebrates being together as a family, and we teach our children the traditional ways and not the colonizers’ [version] of what happened in the past.”

A sad anniversary

Amanda Takes War Bonnet is an Oglala Lakota journalist working as a public education specialist with a South Dakota nonprofit group devoted to ending violence against Indigenous women.

“My mother would always have a nice meal on Thanksgiving, with pies and everything homemade,” she recalls. “It also meant hunting season had started, so the meal was held after the guys [came back from] hunting.”

Thanksgiving now holds little meaning for her.

“Some years back, my son brought this huge turkey from his work to share with family. I didn’t estimate the cooking time right, so we had to start the meal without it,” she said.

“My son died in front of us from a heart attack,” she said. “That big bird dried up in the oven, forgotten.”

She never roasted another turkey after that.

“Maybe someday, we will heal, but for now, ‘Turkey Day’ is just a great holiday to not work and relax with a prime rib roast.”

‘A golden opportunity’

Oglala Lakota journalist James Giago Davies grew up in Rapid City, South Dakota, where churches and charity groups gave out free turkeys and all the “fixings.”

“We were a poor Native family, struggling to survive,” he said. “Thanksgiving was a golden opportunity to get extra food and have a good meal. We never thought of it beyond that immediate pressing reality, and I don’t know of any families from my ‘rez’ who did. Maybe it is different now.”

David Cornsilk, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation from Tahlequah, Oklahoma, grew up in a traditional household where Thanksgiving was never celebrated.

“My dad opposed it, saying there was nothing Indian people had to celebrate in America,” Cornsilk said. “But he never talked about history. It was not until high school that I learned the truth about Indigenous history and then only because I had become a voracious reader of history.”

Years later, Cornsilk married into a Cherokee family he describes as the “polar opposite.”

“Where we were traditional, they were Christian. Where we rejected Thanksgiving, they embraced it and had a huge feast with a large family gathering,” he said.

It is a tradition he has passed on to his children and grandchildren.

“The difference will be that my children and grandchildren know their history,” he said. “We give thanks for our blessings and share our bounty in a land we love with the people we love.”

‘Takesgiving’

Lynn Eagle Feather, a Sicangu Lakota living in Denver, Colorado, says she lost her son to police violence in July 2015 and has been seeking justice ever since.

“Thanksgiving?” she asks. “You mean ‘Takesgiving.'”

She plans to spend the holiday demonstrating outside of a Denver hospital where staff cut off the waist-length hair of 65-year-old Oglala Lakota elder Arthur Janis, without his or his family’s permission, while he was undergoing medical treatment.

“This is Native American Heritage Month,” Eagle Feather said, “and our people are still suffering.”

|

|

|