SEOUL—North Korea’s defiant and accelerated efforts to develop an advanced nuclear arsenal have not been deterred, so far, by the tough new United Nations sanctions imposed in March.

The latest infraction of U.N. resolutions banning Pyongyang’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs occurred Thursday, when the North attempted another intermediate range ballistic missile launch. But the missile crashed seconds after it was fired, according to the South Korean Defense Ministry. The North Korean military conducted a similar mid-range missile test earlier this month that also failed.

In response to the lasted missile test, the United Nations urged North Korea on Thursday to stop “any further provocative actions” and the Security Council held a closed-door meeting to discuss if further responses should be considered.

Pyongyang is also reportedly prepared to conduct its fifth nuclear test at any time, just months after it set off its last nuclear explosion in January.

Sanctions questioned

The new North Korean sanctions passed in March are considered the strongest international measures yet and are meant to pressure Kim Jong Un to reconsider his nuclear ambitions.

But rather than offer concessions, the young North Korean leader has reacted to international pressure with speed and fury, increasing the number and frequency of tests and threatening nuclear strikes against the United States and its allies in Asia.

“Under the current sanctions regime I see little hope for making real progress in denuclearization despite all the fuss about sanctions,” said Ambassador Chun Yung-woo, who was a South Korean national security adviser to former President Lee Myung-bak until 2013, and is now an analyst with the Asan Institute in Seoul.

Ambassador Chun was one of a number of international analysts who discussed the purpose and effectiveness of North Korean sanctions at an Asan Institute forum in Seoul this week.

North Korea has been under United Nations sanctions since it conducted its first nuclear test in 2006. The new measures include banning much of the North’s lucrative mineral trade, inspecting all cargo crossing the border for illicit items, and blacklisting key officials and organizations connected to the North’s nuclear program.

China’s mixed signals

China holds the key to effective sanctions enforcement as 90 percent of all North Korean trade passes through its borders.

Yang Xiyu, a North Korea analyst at the China Institute of International Studies in Beijing, said contrary to reports of lax implementation, the Chinese government has imposed strict requirements that will significantly reduce trade at the Sino/Korean border. “You need to provide a full set of documents and evidence to show the legitimacy of your deal, and such a complicated procedure technically will sharply increase comprehensive costs for businessmen,” said Yang.

However on Thursday, Chinese President Xi Jinping again tempered his support for sanctions with concern for maintaining regional stability. “We will absolutely not permit war or chaos on the peninsula,” said Xi.

Ambassador Chun said Beijing is sending mixed signals that undermine the international commitment to sanctions. “The message that Kim Jong Un will get from China’s position is, ‘Don’t worry about serious consequences, we will pretend to take sanctions, but not unbearable sanctions,’” said Chun.[xyz-ihs snippet=”adsense-body-ad”]

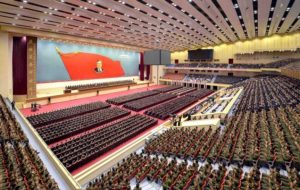

If Pyongyang goes ahead as expected with its fifth nuclear test prior to the commencement of its ruling party congress next week, the international community, including China, will likely consider further sanctions that will impose economic pain beyond those targeting the military and elites.

“If they go further, I believe they will receive the further shocks,” said Yang.

Iran lessons

Even the most comprehensive sanctions regime can take years to persuade an adversary as seemingly determined as North Korea to reconsider its nuclear deterrent.

“Sanctions campaigns take a lot of work. They take a long time to work. That’s one thing I really learned from the whole Iran experience,” said Gary Samore, who worked on Iran and North Korea nuclear issues when he served as President Barack Obama’s White House Coordinator for Arms Control and Weapons of Mass Destruction. He is now an analyst with Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

He noted that it took years for a crippling international embargo on Iranian oil to pressure Tehran to agree to a deal to dismantle its nuclear program.

North Korea’s rush to advance its nuclear and missile technology is likely a recognition that international sanctions will succeed in restricting needed materials and funds in the near future.

Kim Jong Un has openly declared his country as a nuclear state and the recent missile tests suggest that his military has been ordered to speed up efforts to achieve verifiable medium and long range nuclear capabilities.

At some point, Samore said, North Korea may seek a deal to freeze its current nuclear capabilities for easing the sanctions. Then the United States and the international community will have to consider what degree of compromise they are willing to accept. “We need to think about what we are prepared to offer in exchange in terms of partial sanctions relief and assistance, because we’re not likely to get it for free,” he said.

Still, these analysts said, economic sanctions that lead to negotiations offer the best hope for peaceful resolution to the nuclear standoff on the Korean peninsula.

President Obama also recently emphasized increased military deterrence and reliance on missile defense systems to protect the United States and its allies from a potential North Korean attack. But he ruled out taking offensive military action against the North, saying while American allied forces would ultimately win, it would come at a devastating humanitarian cost for South Korea.

Youmi Kim in Seoul contributed to this report.

Source: VOA [xyz-ihs snippet=”Adversal-468×60″]