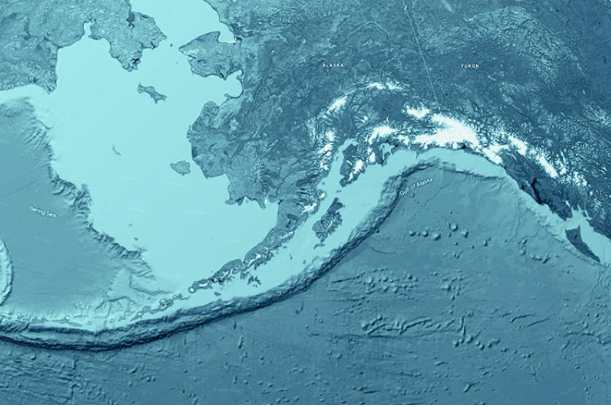

The Arctic is changing, and scientists and residents alike are interested to understand both the reasons for and impacts of these changes, including how it’s affecting fish populations that Alaskans rely on. To explore changing distribution patterns of Pacific salmon in the Arctic, Elizabeth Lindley, a PhD student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, is seeking deeper understanding by considering salmon in the broader system. Lindley and her mentor, Peter Westley, are using three distinct approaches to address three distinct perspectives: people, place, and fish.

To consider expansion of salmon species in the Arctic from the perspective of the region’s people, they hosted the Alaska Arctic Salmon Workshop, which convened Arctic community members and Western scientists. According to Lindley, while the primary focus was to discuss salmon changes, “the holistic nature of Indigenous knowledge really laid the foundation for discussions as the topic of change covered all aspects of Arctic living, not just salmon.” The discussions broadened to include whales, storms, sea ice, non-salmon fishes, river conditions and more.

“The group collectively formed questions and concerns that they felt were of greatest importance in the context of our work,” Lindley added.

To understand the changes that are happening from the perspective of place, they conducted aerial helicopter surveys of the Colville River drainage to search for spawning salmon.

“Randy Brown of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Brendan Scanlon of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game have shared especially invaluable knowledge on where salmon have historically been observed in the Colville River drainage,” said Lindley.

Surprising the researchers, in 2023, spawning aggregations were found in three sites within the eastern Colville River drainage. This provided researchers the opportunity to study the chum salmon themselves and the environments they were spawning in. No chum salmon were observed spawning in the same sites during surveys in 2024. Data collected from the spawning sites will inform the final objective of the project, which is to explore the potential for a match between Arctic spawning environments and early life history requirements, and determining whether the sites allow for temperature-driven embryo development to align with hospitable conditions during hatching.

To look at what’s happening from the perspective of the fish, they are using multiple approaches to assess the thermal potential for spawning and incubation success of establishing salmon. The temperature loggers installed into the chum salmon nests in 2023 and retrieved in 2024 revealed thermally suitable incubating habitat. Temperatures approached but did not drop below freezing, suggesting that liquid water was present throughout the winter. These data will be used to predict hatching and nest emergence times in these spawning sites. Interestingly, genetic analysis run by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game revealed that a significant fraction of observed spawning salmon were born in Alaska, but of Russian/Korean origin.

“Using scientific methods to answer questions that address local concerns was my motivation to start graduate school. This project has shaped me as a scientist by granting me opportunities to gain confidence in doing work that aligns with these values,” reflected Lindley.

Westley and Lindley’s research was supported in part by Alaska Sea Grant, with support and funding from the Alaska Arctic Observatory and Knowledge Hubs, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and with generous logistical support from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

More information on this research, including a short video presentation by Lindley, are available on the Alaska Sea Grant project page Pink Arctic: patterns, processes, and consequences of increasing Pacific salmon in the high north.

[content id=”79272″]