Researchers from NOAA, U.S. Geological Survey and their partners have completed the first high-resolution, comprehensive mapping of one of the fastest moving underwater tectonic faults in the world, located in southeastern Alaska. This information will help communities in coastal Alaska and Canada better understand and prepare for the risks from earthquakes and tsunamis that can occur when faults suddenly move.

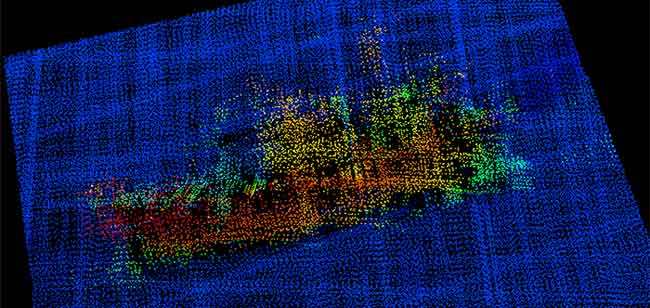

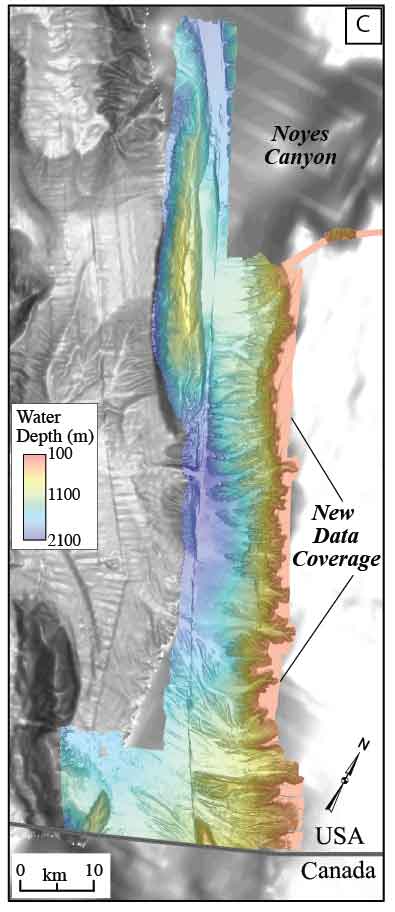

Since 2015, scientists have been gathering data on the Queen Charlotte-Fairweather fault system, a 746-mile long strike-slip fault line that extends from offshore of Vancouver Island, Canada, to the Fairweather Range of southeast Alaska. The team has gathered high resolution bathymetric data through multibeam sonar across 5,792 square miles of the ocean bottom.

The most recent survey came from NOAA Ship Fairweather, with USGS scientists aboard from April through July, when it collected multibeam bathymetric data in an area along the U.S. and Canadian international border in water depths ranging from 500 to more than 7,000 feet deep.

“Providing scientific information to help protect vulnerable communities is one of our most important missions,” said W. Russell Callender, assistant NOAA administrator for the National Ocean Service. “Working with USGS and our state and academic partners, allows us to speed the development of information that can help communities better anticipate and prepare for risks from tsunamis and earthquakes.”

“This project has been a great collaboration on an important scientific issue with significant implications for public safety,” said David Applegate, USGS associate director for natural hazards. “We will apply what we learn from this mapping mission to hazard assessments for Alaska’s coastal communities. Partnering with NOAA reflects the importance of addressing earthquake and associated tsunami hazards to both our missions, and it enables the USGS to bring our geologic expertise to bear on offshore fault structures that have significant onshore implications.”

Fault line activity poses a hazard to the growing populations of Juneau, Sitka, and other communities throughout southeastern Alaska, as well as more than a million annual tourists and the seafloor infrastructure critical for Alaska’s communications and offshore energy industries.

With a slip rate of more than 2 inches per year, this fault may be one of the fastest-moving strike-slip faults in the world. (For comparison, the San Andreas fault in central California slips about an inch to an inch-and-a-half each year.) Movement between the tectonic plates at the fault line has generated six earthquakes of magnitude 7 or greater within the last century. One of those earthquakes, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake near Lituya Bay, Alaska, in 1958 triggered a landslide that sent water 1,720 feet up an adjacent mountainside, one of the highest recorded runups of a tsunami—a rapidly rising turbulent surge of water often choked with debris.

A series of large-magnitude earthquakes and associated aftershocks in 2012 and 2013 spurred research cruises in 2015, in the first systematic effort to study the offshore Queen Charlotte-Fairweather fault system in U.S. territory in more than three decades. A similar effort led by the Geological Survey of Canada has been underway along the portion of the fault located in Canadian territory.

The 2018 Fairweather survey built on five previous USGS-led marine geophysical and geological surveys between 2015 and 2017 in southeastern Alaska aboard a number of research vessels, as well as two cruises led by researchers from the Geological Survey of Canada, Sitka Sound Science Center and USGS. During these surveys, researchers used an array of instruments to collect data on seafloor depth and texture, to profile sedimentary layers beneath the seafloor, and to derive sediment ages.

NOAA nautical charts will be updated with the Queen Charlotte Fault data within a year once the data goes through a standard quality control process – although the fault area is too deep for any obstructions to pose a threat to marine traffic.

This research is part of a larger two-year effort between the NOAA Integrated Coastal and Ocean Mapping Program and USGS to map large portions of the Cascadia continental margin in federal waters offshore of Alaska, California, Oregon and Washington.