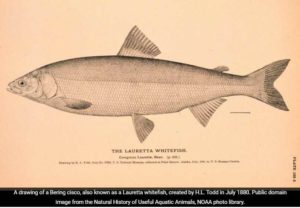

In Alaska’s infinite waters swims a handsome, silvery fish. Until recently, we knew little about the Bering cisco, which exists only around Alaska and Siberia. Then a scientist combined his unique life experiences with modern tools to help color in the fish’s life history.

In Alaska’s infinite waters swims a handsome, silvery fish. Until recently, we knew little about the Bering cisco, which exists only around Alaska and Siberia. Then a scientist combined his unique life experiences with modern tools to help color in the fish’s life history.

Randy Brown is a fisheries biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Fairbanks. Many years before he started that career, he finished high school in New Mexico and then drove up to Alaska. At the town of Eagle, he slipped his canoe into the Yukon River.

For the next few decades, he lived in large part off what the land gave him. As part of that life, he, his wife and two sons lived on the Kandik River. Every July, they floated down that clear tributary to the Yukon for fish camp. On the big river, they netted salmon that made up a good portion of their food, and their dogs’ food.

About 30 years ago, Brown and his family moved to Fairbanks, where he finished his graduate studies and became a scientist.

Brown’s appreciation for fish and the savvy he gained from both his bush existence and professional life has given the world a better understanding of what he calls an “extraordinary species,” the Bering cisco.

Biologists wanted to know more about this creature when, about 15 years ago, Bering cisco was suddenly a featured product of Acme Smoked Fish in Brooklyn, New York.

Smoked whole whitefish is a traditional kosher meal for Jewish families. When supplies of Great Lakes ciscos dwindled, fishermen at the mouth of the Yukon had a replacement in their nets. Buyers found out about the fish, and flew tons of Yukon River Bering ciscos that lower-Yukon residents had caught to New York City.[content id=”79272″]

New York Times reporter Florence Fabricant described the Alaska fish in a Dec. 16, 2008 story:

“Gleaming gold from the smoker, Bering cisco are perhaps even richer (than other whitefish), with almost creamy flesh, making for a tempting accompaniment to serve, with a dab of horseradish-sour cream, with Hanukkah latkes, or as one of the seven fishes on the Christmas Eve table.”

With thousands of the fish being harvested at the mouth of the Yukon River, fishery managers needed to know if the population could sustain the removal of that many individuals.

What did biologists know about the smallish whitefish? Not much. They knew the Bering cisco lived part of its life in the ocean, like salmon. But they did not know precisely where the fish replaced themselves by laying eggs in river gravel.

Brown, who studies subsistence fisheries in northern Alaska, said the Bering cisco mystery made him think of when he was studying sheefish for his master’s degree. As part of that, in 1996, he worked with fishermen using river-powered, rotating fish wheels at a tight section of the Yukon River known as “the Rapids.”

There, Brown gathered data with Stan Zuray, who lives in the nearby village of Tanana. Zuray for many years had taken laptop-activated videos of fish that his wheel scooped up.

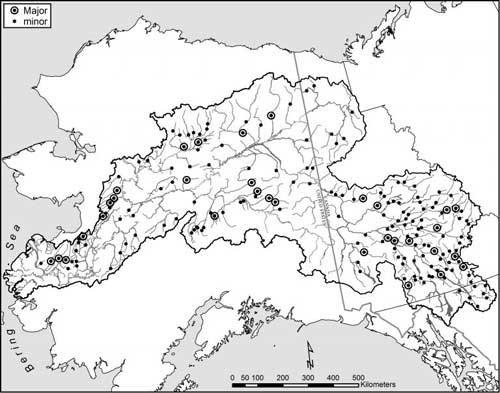

In addition to many salmon images, Zuray’s system captured Bering ciscos, suggesting the whitefish were spawning somewhere upriver of the Rapids, located 90 miles downstream of the Dalton Highway Bridge.

Brown found sheefish — the largest of Alaska whitefish — laid eggs in a highly braided portion of the river where it spills through the Yukon Flats. He suspected spawning Bering ciscos might also favor the same spot, rich in warmish, upwelling groundwater, between the villages of Circle and Fort Yukon.

Brown and fellow biologist Dave Daum implanted tiny transmitters in the abdomens of Bering ciscos at the Rapids in 2012 and 2013. Following the beeps of the transmitters by airplane, they discovered that in late fall the migrating fish were indeed coming to a halt in the three-mile wide swath of river channels between Circle and Fort Yukon.

For a few years, state biologists caught and tagged Bering ciscos in the Yukon Flats in early October. They confirmed the flats as the spot where a majority of Yukon River Bering ciscos were laying eggs.

One year, biologists estimated almost 400,000 Bering ciscos on that spawning ground, making managers feel more secure in establishing a harvest limit of about 25,000 fish at the mouth of the Yukon.

Scientists had even more tools to sharpen the focus on Bering ciscos. Using a bony growth called an otolith that exists in the head of most fish, Brown and others counted growth rings, estimating older fish sometimes reached the age of 14. Working with staffers at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Alaska Stable Isotope Facility, they also teased out strontium/calcium ratio profiles of the otoliths, which told them how long Bering ciscos had spent in salt water (usually a few years).

Brown also has a theory on a quirk of the far-ranging fish. People have caught Bering cisco in the ocean from the outlet of the Yukon River to as far north as the mouth of the Colville River, on Alaska’s North Slope. No one knew where those extreme northern fish spawned.

“I searched all the records I could find, everything I could come up with, and I couldn’t find any sign of Bering cisco going up other streams north of the Yukon,” Brown said.

He suspects that ocean currents flowing northward shove the newly hatched fish passively northward.

“These larvae Bering cisco get blasted out of the Yukon each summer,” he said. “They get swept into every (northern) estuary.”

When they are ready to spawn, those northern fish ignore the nearby drainages and all swim back to the Yukon.

The shiny fish are right now swimming almost everywhere off Alaska’s coast. In addition to the Yukon, smaller numbers of Bering ciscos also spawn in the Kuskokwim and Susitna rivers.

Thousands of those flashy bodies are fattening up, many of them getting ready to nose back into the Yukon River where they were born. Once there, the fish will stop eating and swim hundreds of miles upriver, returning to one of the planet’s great whitefish nurseries.

Source: Geophysical Institute