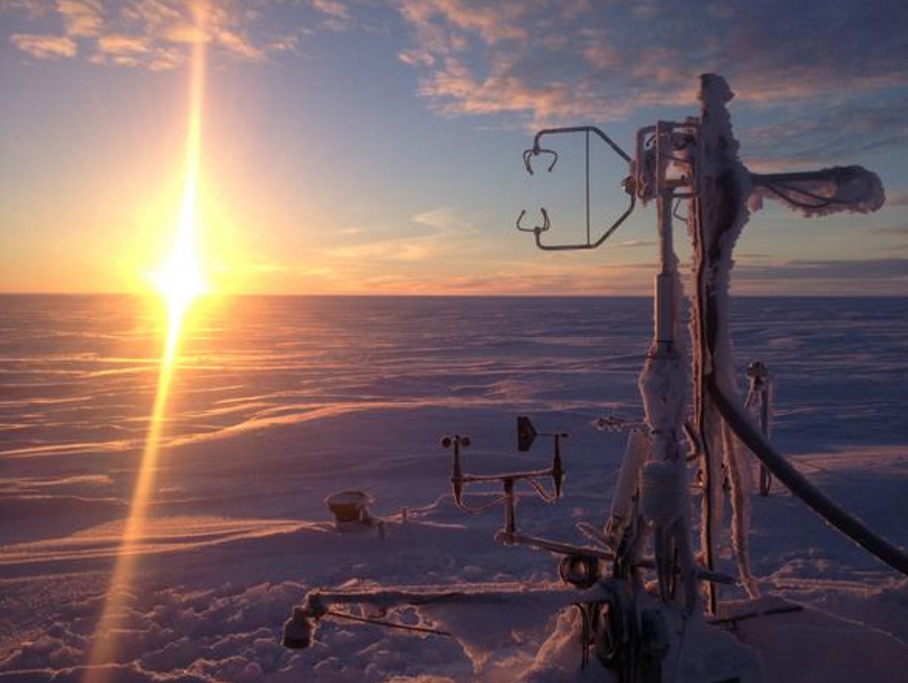

“We began the collaboration when we realized this is also the most sensitive depth for methane hydrate deposits,” Hautala said. She believes the same ocean currents could be warming intermediate-depth waters from Northern California to Alaska, where frozen methane deposits are also known to exist.

Warming water causes the frozen edge of methane hydrate to move into deeper water. On land, as the air temperature warms on a frozen hillside, the snowline moves uphill. In a warming ocean, the boundary between frozen and gaseous methane would move deeper and farther offshore. Calculations in the paper show that since 1970 the Washington boundary has moved about 1 kilometer – a little more than a half-mile – farther offshore. By 2100, the boundary for solid methane would move another 1 to 3 kilometers out to sea.

Estimates for the future amount of gas released from hydrate dissociation this century are as high as 0.4 million metric tons per year off the Washington coast, or about quadruple the amount of methane from the Deepwater Horizon blowout each year.

Still unknown is where any released methane gas would end up. It could be consumed by bacteria in the seafloor sediment or in the water, where it could cause seawater in that area to become more acidic and oxygen-deprived. Some methane might also rise to the surface, where it would release into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas, compounding the effects of climate change.

Researchers now hope to verify the calculations with new measurements. For the past few years, curious fishermen have sent UW oceanographers sonar images showing mysterious columns of bubbles. Solomon and Johnson just returned from a cruise to check out some of those sites at depths where Solomon believes they could be caused by warming water.

“Those images the fishermen sent were 100 percent accurate,” Johnson said. “Without them we would have been shooting in the dark.”

Johnson and Solomon are analyzing data from that cruise to pinpoint what’s triggering this seepage, and the fate of any released methane. The recent sightings of methane bubbles rising to the sea surface, the authors note, suggests that at least some of the seafloor gas may reach the surface and vent to the atmosphere.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy. The other co-author is Robert Harris at Oregon State University.

Pages: 1 2