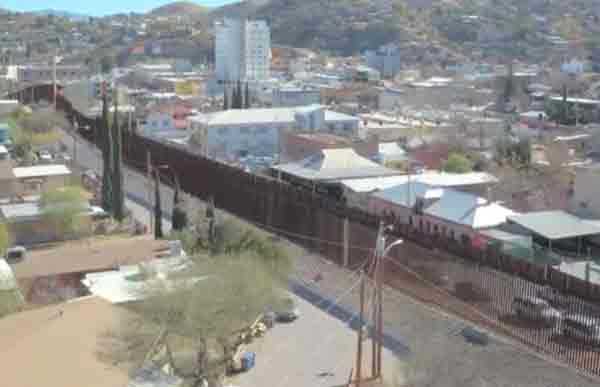

2018 has been a chaotic year at the U.S.-Mexico border, where desperation collided with politics, and children bore the brunt of a debated threat – all of this in the shadow of the still unfunded border wall.

The year did not begin with “a national emergency,” at the border, as Trump claimed or as his critics prefer, a manufactured crisis. In January’s State of the Union speech, Trump outlined his four-pillar immigration plan: a path to citizenship for young people brought to the U.S. as children, the abolishment of the diversity visa lottery, an end to chain migration and…construction of a wall on the southern border.

“These four pillars represent a down-the-middle compromise, and one that will create a safe, modern, and lawful immigration system,” Trump said.

But the Republican-controlled Congress did not agree, failing to pass any immigration legislation. In the 2018 omnibus budget, Congress allotted only $1.375 billion for border security, none of which included construction of a border wall.

[content id=”79272″]

“Repairs, drones and pedestrian fencing, but no wall construction,” Dan Stein, president of the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), lamented in a statement.Like Trump and his supporters, FAIR takes a hard-line position on immigration.

“I am considering a veto,” Trump tweeted a day after Congress passed the budget, in part because “the BORDER WALL, which is desperately needed for our National Defense, is not fully funded.”

The wall had been Trump’s signature promise when he ran for president. His campaign rallies were often punctuated with chants to “build the wall.”

Trump signed the budget bill on March 23 but vowed to never do it again.

Ten days later on April 1, he tweeted for the first time about the migrant caravan.

Migrant caravan

“Getting more dangerous. ‘Caravans’ coming,” the president tweeted.

Americans were largely unaware that some 1,000 migrants were walking toward the U.S. border. Thegroup had left Tapachula, Chiapas, near the Guatemalan border on March 25.

It wasn’t the first caravan.

“These Stations of the Cross’ migrant caravans have been held in southern Mexico for at least the last five years,” the Associated Press reported. But this one still weeks away from the U.S.generated new interest.

On April 4, Trump called up the National Guard, “to protect our country and stop the stream of illegal immigration.”

On April 6, he issued an executive order calling for an end to catch and release, an Obama-era policy that released asylum seekers into the U.S. usually with ankle bracelets to assure their appearance in immigration court.

Family separation

When the migrants crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in May, they were put into detention under a policy announced April 6 by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Under the Zero Tolerance’ Policy, criminal charges were filed against anyone who crossed the border illegally. Since children could not by law be detained with their parents for more than 20 days, thousands were taken from their parents and placed in their own detention centers.

The flow of separated children soon outpaced the government’s capacity to hold them. In mid-June, the Department of Health and Human Services opened a tent city near Tornillo, Texas, to hold 1,200 children. It was later expanded to house 3,500.

Reports of mistreatment and leaked audio of crying children outraged Americans. Separation was becoming a political crisis for the president when he signed an executive order ending it on June 20. Six days later, a federal court ordered the children be reunited with their parents.

But multiple federal agencies had kept poor track of the children — numbered at 2,654 in later court filings — and missed several deadlines to return them. Four months later, 245 children had yet to be reunited with their parents, court documents showed.

Trump’s order also called for families to be detained as a unit while their cases proceeded through the courts. But a federal court denied permission. Unable to separate families or detain them together, immigration authorities fell back on catch and release.

More caravans

Less than a month before the midterm elections, new caravans were reported heading toward the U.S. border.

“Great midterm issue for Republicans,” Trump tweeted.

In the weeks before the Nov. 6 midterms, he warned repeatedly at his rallies and on Twitters about an “assault on our country” and urged the caravans to “TURN AROUND.”

At the president’s request, the Pentagon sent 5,200 active troops to join the 2,000 National Guard members already at the border in late October. Like the Guard, the troops could not legally do police work and were confined to support duties such as stringing concertina wire in advance of the caravan’s arrival, still weeks away.

After the election, the president issued a proclamation that anyone who entered the U.S. illegally would not be eligible for asylum.

The American Civil Liberties Union and other groups immediately sued, arguing U.S. law guarantees the right to request asylum no matter how immigrants get into the country. A federal judge and court of appeals agreed. The government appealed to the Supreme Court in December.

Hundreds of migrants who arrived in Tijuana in mid-November were also blocked when they tried to enter legally at ports of entry. U.S. Customs and Border Patrol admitted only a few migrants each day, claiming they had limited capacity. Waiting times extended into weeks.

Endless Waiting to Enter US at Southern Border

In late November, tensions boiled over. Migrants launched projectiles at border guards, who responded with tear gas. A photograph of a 39-year-old woman from Honduras fleeing the tear gas with her two children went viral.

Up against the wall — again

At year’s end, the wall was back. Trump wanted $5 billion in funding for it. When Democratic congressional leaders Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer demurred during an Oval Office meeting in mid-December, he vowed to shut down the government.

“I am proud to shut down the government for border security,” Trump declared, recalling his vow never to sign a budget that did not include the wall.

Source: VOA