WASHINGTON — Jonah Yellowman, like most Navajos, grew up hearing stories about the Long Walk.

“Some of my ancestors on my father’s side, the Red House clan, they made the walk. They said the Army was trying to get rid of all the tribes without having to use guns.”

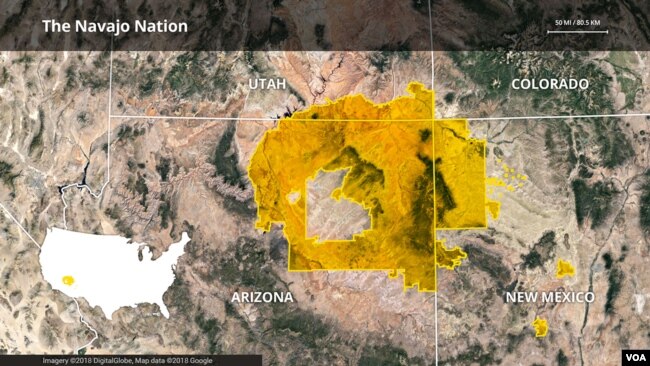

The Navajo, who call themselves the Diné, had lived for thousands of years in the Four Corners region of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Colorado.

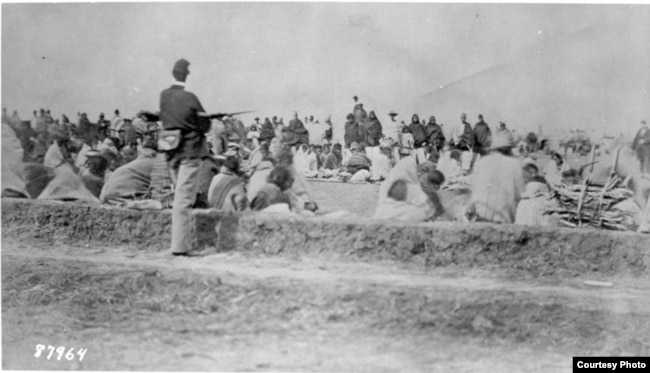

The arrival of white settlers in the 1840s set off a series of conflicts which by 1863 had reached a boiling point. The U.S. Army decided that the only solution was to forcibly relocate the Navajo to the Bosque Redondo, an internment center along the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico. There, remote from settlers, the Navajo might learn to farm and become self-sufficient.

The Journey to H’weeldi

In early September 1863, troops began capturing and forcing groups of Navajo men, women and children along the “Long Walk,” 300-400 miles away to the internment camp the Navajo still call H’weeldi, “the place of suffering.” Many didn’t make the trip, falling victim to starvation, cold or harsh Army tactics.

“Along the way, if some of the ladies that were going to have babies and were falling behind, either somebody helped them or they just got shot right there by soldiers,” said Yellowman, a Navajo spiritual leader from Oljato–Monument Valley in Utah.

Conditions were no better at Bosque Redondo. The landscape was dry, the water alkaline, and the rations meager and unfamiliar. Survivors recalled eating flour paste and boiled coffee beans. To ward off starvation, some even ate rats and skunk.

“The soldiers used to take the babies from their mothers at night time so that the mothers wouldn’t try to escape overnight,” said Yellowman. “They herded the little ones into a round corral out in the middle of nowhere, like sheep.”

One night, he said, one of the babies broke out of the corral and crawled back to the Navajo campsite. His mother, seeing her chance, took him in her arms and fled into the night, making the long trip home entirely on her own.

That woman was Yellowman’s great-great grandmother.

The Return to Dinétah

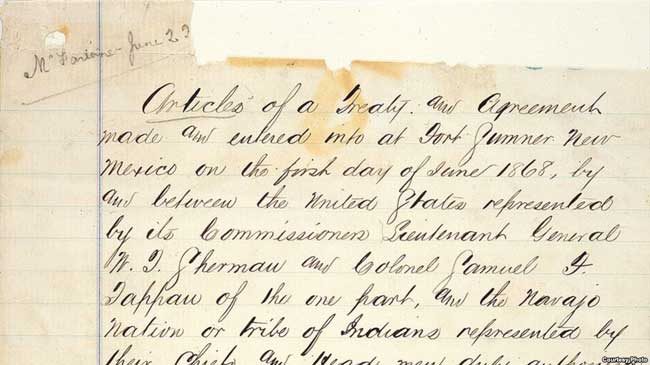

The Army’s social experiment at Bosque Redondo lasted five years before it was deemed a failure. Corn crops had failed repeatedly. The Navajo had grown increasingly unhappy, and the government realized it was spending $1.5 million a year to feed its prisoners.

On June 1, 1868, the Navajo signed a treaty that allowed them to return to Dinétah, their homeland.

“You can just imagine the stories that I heard from our elders back when I was a young boy,” said Russell Begaye, president of the Navajo Nation. “When the announcement was made that the Navajos could go home, a lot of the elders couldn’t wait. They started walking the evening before and walked all night toward our sacred mountain [Mt. Taylor, in northwest N.M.]. They told me that there was a lot of celebration, a lot of tears.”

State of the Nation

Today, 150 years later, the Navajo Nation has expanded to cover more than 27,000 square miles of land within the states of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, and has a population of 180,000.

It has built a modern economy based on traditional farming, ranching and the arts and is actively working to promote investment and economic development through a wide variety of commercial and industrial enterprises, including gaming.

But the Nation still lags behind the rest of the U.S. The median household income stands at $27,400. Nearly half the population is unemployed. A third of Navajo homes lack electricity; 40 percent lack running water.

“We’ve always been behind in development, but now we want to change that,” said Begaye. “We have plans to get into high-tech industry, all the way from robotics to aircraft to additive manufacturing.”

And even cryptocurrency, he added, “because we want to be on the cutting edge of everything that is happening today.”

But there are challenges ahead. The Navajo Nation is sovereign, meaning it has the right to govern itself, but it is still subject to federal laws, which Begaye said impede its ability to expand.

“During the last discussion on the tax bill, we asked members of Congress to be able to issue private activity bonds,” said Begaye. “We fought for it, we didn’t get it, and we’ll keep fighting until we have the same access to investment as every city and town in the United States.”

Even so, Begaye said the Navajo Nation has much to celebrate this week as it marks the anniversary of the 1868 treaty.

“We are now the largest tribe in the nation, and we have the largest land base of all the tribes,” he said.

To mark the occasion, the tribe organized a 400-mile run, retracing their ancestors’ steps from Bosque Redondo to Window Rock, Arizona. And for the first time ever, an original copy of the treaty will go on display at Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, where it will be translated into Navajo so that all Diné can read it.

Source: VOA

[content id=”35021″]