A few years ago, Link Olson wanted students in his mammalogy class to see one of the neatest little creatures in Alaska, the northern flying squirrel. He baited a few live traps with peanut butter rolled in oats and placed them in spruce trees.

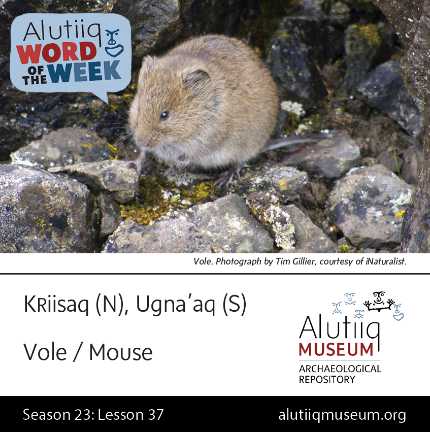

When he returned the next day, he found no flying squirrels. Instead, peering back at him were the beady eyes of the mice of the north, red-backed voles.

The curator of mammals at the University of Alaska Museum, Olson knew a bit about northern red-backed voles. He thought back to the few vole papers he had read and did not remember a sentence about their ability to climb.

A search led to just two references. One is a mention from author and biologist Ron Smith in his book about Alaska natural history: “This vole has been seen in trees.” The other was from me, in a column I wrote about a vole I saw in a spruce tree at 40 below.

Olson wanted to document the northern red-backed vole’s climbing in a science journal. For help, he didn’t have to look far. Working with him in the mammalogy lab was a guy quite enthusiastic about voles.

“I was immediately intrigued,” said Jon Nations, who will soon move to Baton Rouge to pursue a Ph.D. in mammalogy. “Despite these animals being found from Hudson Bay to Scandinavia, nobody had studied or written about them climbing trees. It seemed like it would be fun.”

Nations applied for grants. He raised enough money to design and execute a study. Near Fairbanks, he attached traps to the limbs of spruce trees, again baiting them with peanut butter and oats. He also set up motion-sensor cameras across from trees smudged with peanut butter.

It did not take long for the most common small mammal in Interior Alaska to appear.

Nations captured voles more than six feet up in trees. His camera documented voles climbing up and down trees. One executed a pull-up on a branch to climb when it could have scampered up the trunk. A video shows another zipping up a non-baited tree in the background.

Nations’ electric eye also recorded voles climbing down trees head-first, showing an ability to pivot at the ankle just like red squirrels. Very few creatures can pull this off.

“Most mammals can probably get up a tree, but head-first descent is another thing,” Nation said.

“Cats are an excellent example of that,” Olson said. “They climb up just fine. But then we have a problem, Houston.”

The red-backed vole’s ability to climb is apparent to any Alaskan who has seen them on a birdfeeder or inside the house. Nations and Olson saw value in documenting the behavior in the Journal of Mammalogy because it may change what researchers think about climbers.

“The vole’s is not a body plan people associate with climbing,” said Nations, referring to its stubby legs and a tail that looks like it’s been chopped in half. “No red-backed vole fossil would be associated with climbing. It shows you can’t judge an animal’s behavior by looking at it physically.”

In the column I wrote in 2006, biologist Ian van Tets offered a few reasons why a vole might climb a tree in midwinter (they spend most of their time active beneath the snow). It might be escaping a weasel hunting its tunnels, other voles might have kicked it out, or it might be looking for food.

Nations got evidence for the latter when one of his cameras captured a vole reaching up with its front paws from where it perched on a limb. The vole snatched a beard of lichen from another branch and started munching it.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.