WASHINGTON — The recent anti-Muslim attack in Portland, Oregon, has highlighted an alarming rise in hate crimes across the U.S. targeting Muslims, African-Americans and other groups.

But hate crimes against Native Americans often don’t often make headlines, which they say is part of a pattern of discrimination and violence dating back generations. They worry they may also see an upsurge in hate crimes against Native communities.

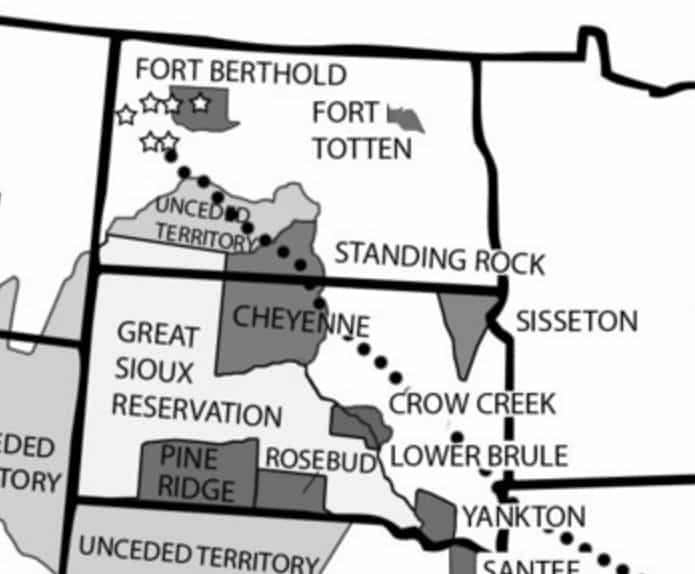

“There’s an increasing sensitivity here, as in other places,” said Charles Abourezk, a South Dakota lawyer, indigenous rights activist and Chief Justice of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Supreme Court. “Our area is increasingly conservative and more increasingly susceptible to the same kind of growing backlash or regression in terms of race politics that we are seeing in the rest of the country.”

Discrimination against Native Americans is widespread, he said, citing personal experience.

Just last year, former U.S. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell attended tribal celebrations marking the Battle of the Little Big Horn in Montana.

“A pick-up truck came in with a bunch of white fellows in back, and they started waving scalps … they were really just wigs. What kind of message are they trying to tell the Indians?” he said. “Indian kids feel the impact. They grow up feeling they have no self-worth.”

He believes that is one reason for a high rate of suicide among Native youth.

Insufficient data

The FBI relies on local police agencies to voluntarily report hate crimes. The Bureau catalogued 4,200 hate crimes in 2015, 3.4 percent of them against Native Americans and Alaska Natives. The figure is statistically significant among a people who represent only one percent of the total U.S. population.

Barbara Perry, a global hate crime expert at Canada’s University of Ontario Institute of Technology and author of “Silent Victims: Hate Crimes Against Native Americans,” believes those numbers are higher. Her studies show that only about 10 percent of victims report hate crimes to tribal or local police.

“The reasons include a sense that they won’t be taken seriously, that they may in fact suffer secondary victimization, harassment or verbal abuse from law enforcement,” she said via email. “They may also be reluctant to involve ‘outsiders’ for fear retaliation by the perpetrator.”

Some hate crimes take place on reservations, where tribal police resources may be thin. And, as a 2014 study showed, police may also be confused about what, exactly, constitutes a hate crime.

U.S. law defines a hate crime as a “criminal offense against person or property motivated partly or entirely by an offender’s bias against a particular race, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation.” Because hate crimes are classified as federal crimes, they fall under FBI, not local, jurisdiction.

Evidence of bias might include membership in hate groups or using racial slurs during an attack, as demonstrated in 2012, when three New Mexico men with ties to white supremacist groups kidnapped a developmentally-disabled Navajo man, branding him with a swastika.

But motive can sometimes be tough to prove, as in the 2015 case of a non-Native parks worker who walked into an alcohol treatment center Riverton, Wyoming, and shot two sleeping men, both members of the Northern Arapaho tribe. The shooter said he was angry about having to clean up after homeless men in public parks and would have shot them regardless of their race.

Some jurisdictions intentionally avoid labeling attacks as hate crimes.

“They would much rather prosecute as a regular crime than admit that there’s racial hatred involved. They’re playing politics,” said Abourezk.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC ), which tracks hate groups, recorded 900 hate and bias incidents since November, but says the actual numbers may be higher.

“The reality is that any community that has been targeted by any hate crime should be concerned in a political climate like this,” said SPLC investigator Ryan Lenz.

In late May, a man driving a “monster” pick-up truck deliberately ran over two members of the Quinault Indian Nation at a campground in the state of Washington, killing one. Tribal witnesses said he shouted racial slurs and “war whoops,” but sheriffs said they found no evidence of a hate crime.

Source:

VOA [xyz-ihs snippet=”Adsense-responsive”]