|

An online survey of 900 consumers of three of the United States’ most popular cigarette brands suggests that adopting standardized cigarette packing may reduce consumers’ misconceptions that some cigarettes are less harmful than others, reports a team of researchers led by University of California San Diego School of Medicine and published in BMJ Tobacco Control .

Standardizing cigarette packaging may reduce misconceptions that some brands are less harmful than others.

“Some companies have marketed their cigarettes as ‘low tar,’ ‘natural’ or ‘organic’ but cigarettes marketed with these terms are not safer. Despite passage of a 2010 law that banned this practice, there are still more than 2.5 million U.S. consumers who continue to believe they are using a brand of cigarettes that might be less harmful,” said first author Eric Leas, PhD, who was part of the research team while a graduate student researcher at UC San Diego and is now a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University School of Medicine.

In previous research, 67 percent of Natural American Spirit consumers said their cigarettes were less harmful than other brands. In this analysis, led by John P. Pierce, PhD, Professor Emeritus in the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center, the researchers assessed whether smokers thought that Natural American Spirit cigarette packaging, which contains terms like “natural” and “additive-free,” implies that this brand is safer and whether repacking them in plain containers would reduce that interpretation.

In Australia and several European countries, standardized packaging has been used to remove marketing cues that may lead consumers to perceive certain benefits from any one brand.

“Australia’s model of cigarette packaging has altered how consumers see brands,” said Pierce, senior author of the study. “We wondered if standardized packing would also impact American smokers’ perceptions of harm that is conveyed through cigarette packing. And, it did.”

To test the hypothesis, researchers asked survey participants to rate their perception of the packaging design of Natural American Spirit or the two most popular U.S. brands: Marlboro Red and Newport Menthol.

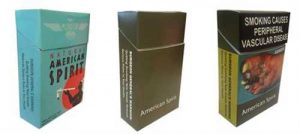

Participants between the ages of 21 to 50, who smoked cigarettes from at least one of the brands within the past seven days of the survey, were randomly assigned to view and rate images of cigarette packages. They viewed either an existing cigarette package from the manufacturers or one of two plain packages that the researchers developed: one removed tobacco industry branding and replaced it with a single color, while the other had the plain packaging and a graphic warning image and label similar to the Australian model.

Survey participants rated the Natural American Spirits packaging 1.9 times higher than Marlboro Red packaging and 1.7 times higher than Newport Menthol packaging on a scale measuring their belief that the packaging implied the cigarettes were safer. However, the difference in implied safety between the latter two brands was not statistically different.[xyz-ihs snippet=”adsense-body-ad”]When comparing across packaging styles, respondents’ ratings of the implied safety of the plain packaging of Natural American Spirits were 1.7 times lower than current U.S. packaging and ratings of the packaging of Natural American Spirits with graphic warning images were 5.4 times lower than current U.S. packaging.

“No tobacco brand has provided evidence that their products reduce the health risks associated with cigarette smoking. It is all about marketing,” said Pierce. “Standardized packaging can reduce consumers’ beliefs about the safety of cigarette brands that include words like ‘natural’ on packaging and instead display a common warning of the harms of smoking.”

There was no clinically meaningful difference between implied safety of the three brands when respondents viewed the brands with the plain packaging or packaging with graphic warnings.

“These findings suggest that plain packaging may be a potential policy solution for ensuring that cigarettes are not marketed as ‘safer,’ a practice that is now essentially banned in the United States,” said Leas.

Co-authors include: Claudiu V. Dimofte, San Diego State University; Dennis R. Trinidad and David R. Strong, UC San Diego.

This research was funded, in part, by the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA190347) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (T32HL007034).

Source: UCSD