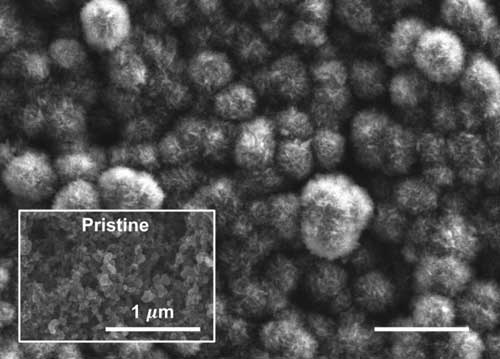

Image of Pacific cod larvae photographed under a microscope.

Scientists released results of a study showing that larval Pacific cod response to elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) levels varies depending on its stage of development. In laboratory experiments, NOAA Fisheries scientists and partners specifically examined larval cod behavior, growth, and lipid composition (the fats needed for storing energy and building muscles). As excess CO2 from the atmosphere dissolves in the ocean, pH is lowered and the ocean increases in acidity, in a process called ocean acidification. Studies like this are important because most marine fish mortality occurs at the larval stage of development and the high-latitude oceans where Pacific cod and other important commercial fisheries occur are expected to be among the most vulnerable to ocean acidification.

“Changing environmental conditions can impact species in multiple ways and not all life stages may respond in the same way,” said Tom Hurst, NOAA Fisheries scientist and lead author of a new paper in Marine Environmental Research. “We wanted to explore this because it has implications for the sustainability of Pacific cod and other important fish stocks in Alaska.”

Hurst and a team of scientists from the Alaska Fisheries Science Center; and the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and the Cooperative Institute for Marine Resources Studies at Oregon State University conducted two laboratory studies to evaluate larval fish sensitivity to elevated CO2.

Behavioral Study

In the ocean, light plays an important role in directing the movements of fish and enabling feeding. The behavioral study showed that when exposed to elevated levels of CO2 four- to five-week-old cod larvae moved more quickly to areas of higher light levels than those raised at CO2 levels currently present in Alaska seawater. While such changes in response to light have been seen in several other fishes exposed to high CO2, scientists are just starting to explore the consequences of these behavioral shifts.

Growth and Energy Study

In the second study, scientists looked at larval fish growth rates when exposed to elevated CO2and fed two different diets, one of which was more lipid-rich (nutritious). Scientists measured fish at two weeks and five weeks old. Regardless of the diet, two-week-old larvae reared at elevated CO2 levels were smaller than larvae reared at current CO2 levels. Interestingly, by five weeks of age, the CO2-exposed fish seemed to have recovered from their slow start.

According to Hurst, the observed differences in growth rates at two weeks vs. five weeks are most likely due to the changing physiology of larvae as they develop. However, it is possible that by the time they reach five weeks old cod larvae are able to acclimate to the effects of elevated CO2. The scientists also suggest that the fast growth of older larvae may be facilitated by behavior changes that stimulate more aggressive feeding.

Ongoing Ocean Acidification Research

This research is part of a larger effort by NOAA to understand the potential consequences of ocean acidification on Alaskan fisheries and the communities that rely on marine resources for nutrition and their economy.

Previous laboratory studies have examined walleye pollock, rock sole and crab species. “The lack of a consistent response among species to elevated CO2 levels continues to challenge our ability to draw large-scale conclusions about the ecosystem impacts of ongoing ocean acidification. But this research adds one more piece to the puzzle and to furthering that understanding,” said Hurst.

Next Steps

Hurst plans to work with partners at Oregon State University to take what he has learned from these studies and other ongoing research to develop computer models to better predict how ocean acidification may affect Pacific cod and pollock larval survival, recruitment (growth to maturity) and adult fish populations in the Bering Sea over different time scales – that is in 20 to 100 years from now.

Funding for this research was provided by NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program and NOAA’s Living Marine Resources Cooperative Science Center.

Source:NOAA