The Alaska village of Brevig Mission lies on the Bering Sea coast west of Nome. The residents allowed a breakthrough in developing a modern vaccine for the Spanish flu of 1918.

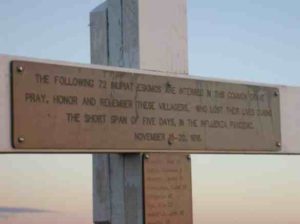

One-hundred-two years ago, a strain of influenza virus spread across the globe, eventually reaching Brevig Mission in Alaska. Five days after the flu hit the Seward Peninsula, 72 of the 80 villagers in Brevig Mission were dead.

Through a series of events suited to a detective novel, researchers made a connection between Brevig Mission and the flu virus that helped prevent another outbreak of the 1918 flu, one of the worst epidemics ever experienced.

The 1918 flu, which infected 28 percent of people in the United States, killed 675,000 Americans. More than 20 million people died worldwide, most of them young adults.

Johan Hultin made it a personal mission to find a sample of the 1918 virus he calls “the most lethal organism in the history of man.”

A native of Sweden, Hultin was studying microbiology at the University of Iowa in 1949. There, he overheard a virologist say that the clue to understanding the 1918 flu might be found in the bodies of victims who were buried in permafrost.

Before he returned to Sweden, Hultin made a recreational trip up the Alaska Highway in 1949 with his wife. In Fairbanks, he met Otto Geist, the anthropologist whose work led to the founding of the University of Alaska Museum.

When Geist heard of Hultin’s interest in the 1918 flu, he introduced Hultin to Lutheran missionaries who gave Hultin church records from Alaska villages in 1918. The records included detailed information on the dead, including where they were buried.

After the sudden fatalities at Brevig Mission, officials of Alaska’s territorial government hired gold miners from Nome to dig a grave large enough for 72 bodies. Driving steam points into the permafrost on a rise near the village, the miners thawed a hole 12 feet wide, 25 feet long and six feet deep. The bodies buried there remained somewhat preserved by the frozen soil surrounding them.Hultin looked at an Alaska permafrost map and selected Brevig Mission as a place that met the requirements of massive flu mortality and frozen ground that might have preserved bodies.

Hultin flew to Brevig Mission in 1951. With permission from Native elders, Hultin, Geist and two Iowa researchers opened the mass grave, marked by two crosses.

The names of 72 people who died in the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic are inscribed in metal plates on a cross over their common grave in Brevig Mission.

Hoping to study the virus to see what had made it so deadly, Hultin’s goal was the retrieval of live flu virus from the lungs of the victims. He removed lung tissue from four bodies, closed the grave, and returned to Iowa. In a lab there, he tried to revive the virus using a number of different methods. After he failed, Hultin resigned himself to perhaps never solving the mystery.

Fast-forward 46 years, to 1997. Hultin, then 72 and living in San Francisco, read an article in the journal Science written by a molecular pathologist, Jeffery Taubenberger. Taubenberger is chief of the viral pathogenesis and evolution section at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland.

Taubenberger and his colleagues developed a method to isolate genetic material from viruses that he applied to the tissue of two young soldiers who died of the flu in 1918. He had access to autopsy specimens preserved since the Civil War.

The only drawback to Taubenberger’s samples, encased in chunks of paraffin the size of a thumbnail, was that they were extremely small. He needed more to work with, but he did not know where to find tissue of people killed by the 1918 flu until Hultin wrote him.

Using $3,200 from his savings account, Hultin traveled to Brevig Mission in August 1997. After receiving permission from the elders, he again opened the mass grave.

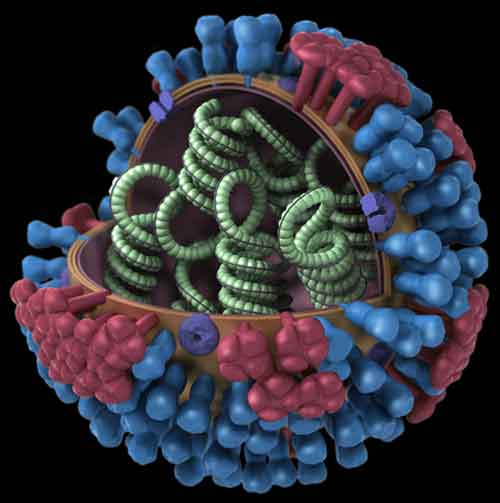

With the samples from the obese woman, in 2005 Taubenberger and his colleagues reconstructed the virus. They determined it had originated in birds and had mutated to infect people.At a depth of seven feet, he saw what he was looking for: a well-preserved body. The body was that of an obese woman. Her lungs, which Hultin removed, were well preserved. Hultin said the body’s excess fatty tissue had insulated the lungs from decay during brief periods of permafrost thaw.

Using this information, researchers developed a vaccine and assured that the Spanish flu would never again infect anyone with access to modern medicine.

[content id=”79272″]

“The only sample we (found was) there because the elders of Brevig Mission let me go back into the grave again,” Hultin said in a 1998 interview over the phone from San Francisco. “They gave us the opportunity to do something good — not just for themselves but for the whole world.”

An update to last week’s column: Sea-ice scientist Melinda Webster, who was hoping to be headed to Svalbard right now and moving toward an eventual bunk aboard the research ship Polarstern frozen in the northern ice, has been delayed. She is waiting out travel restrictions due the COVID-19 virus that has affected everyone worldwide.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. Versions of this column ran in 1998 and 2014.