Glass beads the size of blueberries found by archeologists in a Brooks Range house-pit might be the first European item ever to arrive in North America, predating the arrival of Columbus by a few decades.

Made in Venice, Italy, the tiny blue beads might have travelled more than 10,000 miles in the skin pockets of aboriginal adventurers to reach Bering Strait. There, someone ferried them across the ocean to Alaska.

At least 10 of the beads survived a few centuries in the cold dirt of three locations in northern Alaska. Archeologists recently unraveled the mystery of the beads in a paper published in the journal American Antiquity.

Mike Kunz, one of the authors, is an archeologist with the UA Museum of the North. He retired in 2012 from the Bureau of Land Management after three decades as an expert on ancient people of Alaska north of the Arctic Circle. Working for BLM, he visited Punyik Point several times.

Punyik Point, a mile from the Continental Divide in the Brooks Range, is unoccupied today. It was a seasonal camp for generations of inland Eskimos.

Punyik Point was on ancient trade routes from the Bering Sea to the Arctic Ocean, and was probably a dependable place to hunt caribou as the animals moved in fall and spring, Kunz said.

“And, if for some reason the caribou didn’t migrate through where you were, Punyik Point had excellent lake trout and large shrub-willow patches,” he said.

Archeologists have dug at Punyik Point for a long time. It’s where William Irving of the University of Wisconsin in the 1950s and 1960s found two turquoise beads, each with a hole through its center.

In 2004 and 2005, Kunz, BLM archeologist Robin Mills and other experienced scientists returned to Punyik Point using funding for sites that might be in danger of eroding away. There, they found three more of the beads near some copper bangles — metal adornments that resemble flat hoop earrings — and other metal bits that might have been part of a necklace or bracelet.

[content id=”79272″]

Archaeologists often find “trade beads” at Native American archeological sites. Europeans and others created glass beads using technology that didn’t exist in Native cultures. Explorers carried them to trade with aboriginal people they encountered. Dutchman Peter Minuit included trade beads in his deal for Manhattan Island in 1626.

Kunz and Mills do not often find beads at prehistoric Alaska sites. They were aware of the similar beads Irving found decades before, but they had a tool that Irving did not: accelerator mass spectrometry carbon-dating.

Kunz and Mills had also found a carbon-based life form to which they could apply a test. Wound around one of the metal bangles were plant fibers, preserved from years of burial a few inches beneath the ground surface.

They sent the twine, probably the inner bark of a shrub willow, in for radio-carbon testing. The results came back a few months later.

“We almost fell over backwards,” Kunz said. “It came back saying (the plant was alive at) some time during the 1400s. It was like, Wow!”

With that result, later backed up by similar dating on objects found near the same beads at two other arctic Alaska sites, the archaeologists saw that those pea-size objects told a big story.

“This was the earliest that indubitably European materials show up in the New World by overland transport,” Kunz said.

The beads in the tundra of northern Alaska came from Venice, on the Adriatic Sea half a world away. Kunz and Mills found that out by studying the history of glass-bead making in the city of Venice.

Along with the radiocarbon dating of the Alaska twine and charcoal found near the beads, they figured the beads arrived at Punyik Point sometime between 1440 and 1480, years before Columbus was even thinking of his journey.

How did the beads — found in no other archeological site west of the Rockies — make their way from the canals of Venice to a plateau in the Brooks Range?

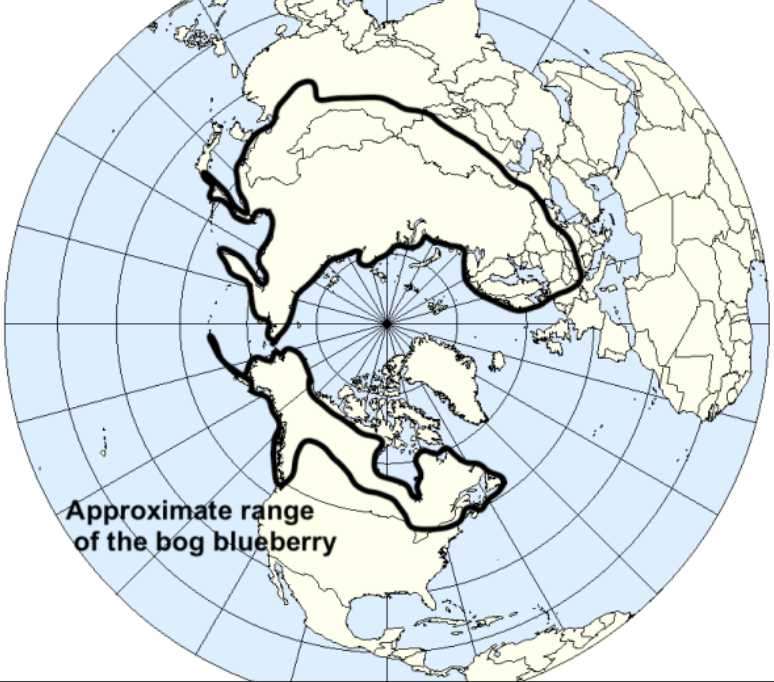

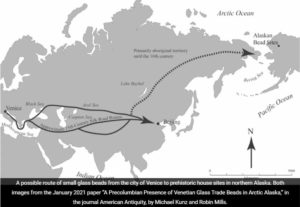

In the 1400s, craftsmen in the city-state of Venice traded with people throughout Asia. The beads might have traveled in a horse-drawn cart along the “Silk Road” eastward toward China. From there, “these early Venetian beads found their way into the aboriginal hinterlands, with some moving to the Russian Far East,” the authors wrote in their recent paper.

In the 1400s, craftsmen in the city-state of Venice traded with people throughout Asia. The beads might have traveled in a horse-drawn cart along the “Silk Road” eastward toward China. From there, “these early Venetian beads found their way into the aboriginal hinterlands, with some moving to the Russian Far East,” the authors wrote in their recent paper.

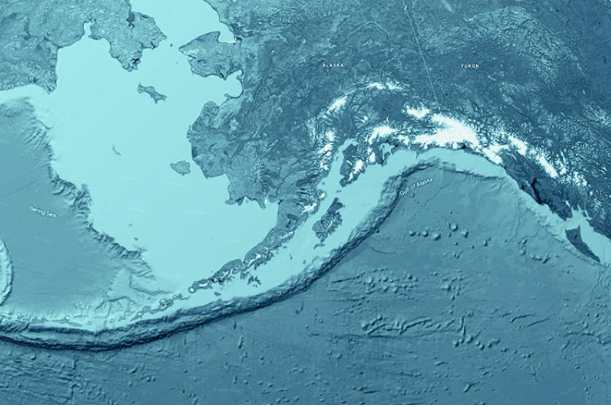

After that great journey, a trader may have tucked the beads into his kayak on the western shore of the Bering Sea. He then dipped his paddle and made passage to the New World, today’s Alaska. The crossing of Bering Strait at its narrowest is about 52 miles of open ocean.

Kunz and Mills think the beads found at Punyik Point and two other sites probably arrived at an ancient trading center called Shashalik, north of today’s Kotzebue and just west of Noatak. From there, people on foot, maybe travelling with a few dogs, carried them deep into the Brooks Range.

Someone at Punyik Point might have strung the exotic blue beads in a necklace, which they lost or left behind as they walked away. The tiny blue spheres rested for centuries at the entrance to an underground house north of the Arctic Circle, waiting to be found.

Source: https://www.gi.alaska.edu/alaska-science-forum/blue-beads-tundra-first-us-import-europe