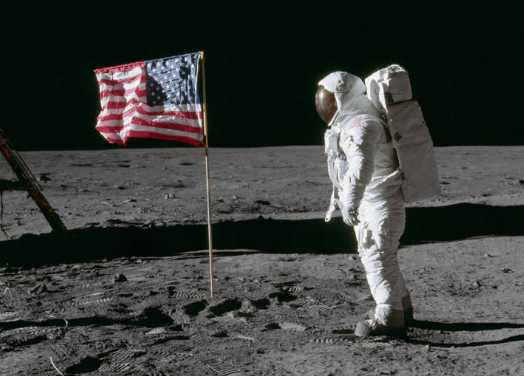

The Mesa Site rises just north of the Brooks Range in northern Alaska.

Now as quiet as wind whispering through grass, a plateau rising from the flats of northern Alaska was for thousands of years a lookout for ancient Alaskans. Those people later vanished, perhaps moving on to populate the Americas. A scientist is using what little they left behind to find out more about those hunters of long ago.

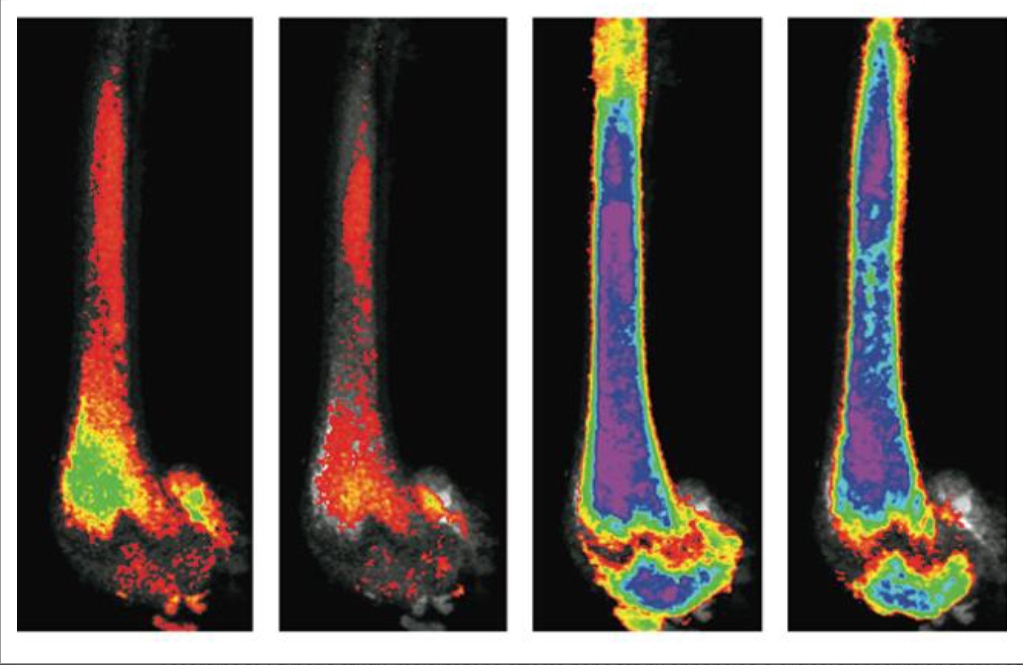

That scientist is Stormy Fields. She works in the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. There, she vaporizes specks of blood, feather, muscle tissue, bone and other organic material. The emitted smoke helps scientists determine — among many other things — where a mammoth wandered across the Alaska landscape thousands of years ago.

Fields, also a master’s degree student, recently saw an additional opportunity to use the lab’s tools on burned material a scientist gathered in gallon-size bags from the Mesa Site more than 20 years ago. Her goal is to see if the hunters there — steppe bison specialists — were also eating fish.

What is the Mesa Site?

A star indicates the location of the Mesa Site in northern Alaska.

In 1978, now-retired Bureau of Land Management archaeologists Mike Kunz and Dale Slaughter explored a hill that rises 180 feet above the foothills of the west-central Brooks Range. What Kunz named the Mesa Site was one of the few stony outcrops in the area. Oil developers wanted to use the rock for construction of a nearby airstrip.

On top of the Mesa, the archaeologists found ancient projectile points, stone tools and blackened areas the size of their open hands that they recognized as the remnants of ancient campfires. They found 40 of those dark circles.

During the next few decades, Kunz and many others returned to the Mesa Site. They discovered that the stone points with which the Mesa people tipped their weapons were strikingly similar to those that Native Americans of the U.S. Great Plains used to kill bison.

In a paper he wrote on the Mesa Site, Kunz noted that the hunters there abandoned that excellent lookout about 9,700 years ago. For the next 2,000 years, there were probably few or no people present on Alaska’s North Slope.

Why? Kunz and UAF’s Dan Mann think that rapid climate change at the end of the last ice age transformed northern Alaska.

The encroachment of the ocean from sea-level rise and the slow flooding of the Bering Land Bridge caused an increase in precipitation around the North Slope.

What was once an Arctic prairie with grasses that fed mammoths, horses and bison transitioned to a place influenced by wetter and warmer conditions. That meant the increase of cottongrass and other tussock tundra plants — favored by few mammals — and mosquitoes, favored by none.

The departed people of the Mesa might have then helped to populate the Americas, as Kunz wrote: “As early as 14,500 years (ago), arctic immigrants . . . could have worked their way south along the coast to a point in temperate North America.”

In the fireplace residue Kunz donated to the UA Museum of the North, Fields sees an easy resource she can process. The Mesa Site has yielded no useful bones for scientists to identify particular animals. But with the capabilities of UAF’s isotope lab, the grit could reveal remains of bison, muskoxen or caribou, as well as the presence or absence of fish that ancient people may have cooked.

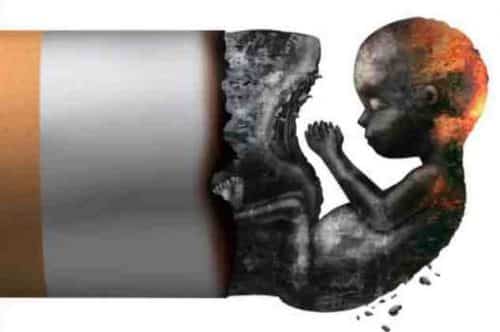

Scientists recently determined that the ancient people of Alaska south of the Arctic Circle were eating salmon at about the same time.

“I am curious to know if the megafauna specialists that were hunting on the North Slope were expanding their diet to include fish like the people of the Interior were,” Fields said. “Whatever results we get will be exciting.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.

[content id=”79272″]