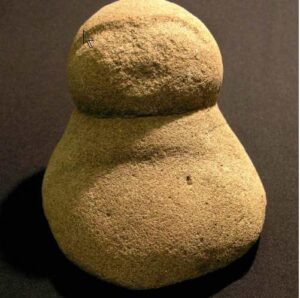

Battered Thing — MuRutuumasqaq

Unaqaq yaamaq giinangq’rtuq. – This pounded rock has a face. muRutuumas

Alutiiq people crafted stone into a variety of useful tools, turning Kodiak bedrock into subsistence gear, utensils, and artwork. There were three major ways of working stone. People chipped glassy chert into elegant arrows and hide scrapers. They ground slate into sharp-edged ulus and slender spears, and they battered or pecked water-rounded cobbles into sinkers, mauls, and stunning sculptured lamps. The Alutiiq word muRutuumasqaq literally means a “thing that was hammered/battered,” referring to objects made by pounding one rock against another.

People made pecked stone objects from a variety of commonly available, local stones–granite, greywacke, and sandstone. Stone pecking is slow, time-consuming work. Recent experiments suggest that the best way to shape a cobble is with two stones, using a hammerstone to drive a pecking stone. Many pecked stone objects also took advantage of the natural shape of a cobble as part of the tool design. For example, to create a sinker for deep sea fishing, craftsmen pecked grooves into a spherical beach cobble to form a channel for attaching a line. Alutiiq people made pecked stone artifacts for thousands of years. Some of the archipelago’s earliest assemblage, those over 7,000 years old, hold pecked stone sinkers and oil lamps. However, about 2,000 years ago, pecked stone artistry flourished, as craftsmen shaped and decorated stone oil lamps. Some examples have sunken designs pecked into the bowl or outer edge of the lamp. Others have sculptural elements that appear in relief along the lamp rim or rise from a lamp’s bowl. These small, intricate carvings are particularly astounding when you consider they were made by pecking.