Caribou graze in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

The Alaska we experience today and our children will experience in the future is not the Alaska of the past.

According to the 2024 Arctic Report Card, released this week by the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration and co-authored by ten University of Alaska Fairbanks scientists, warming is affecting caribou populations, heat-trapping gas releases and many other parts of the ecosystem.

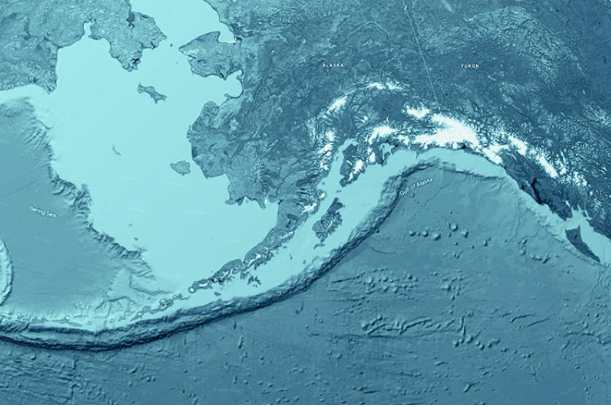

This year is on track to be the world’s hottest year. And for the 11th year in a row, the Arctic warmed more than the global average. Though temperatures in Alaska did not set records in 2024, it was still among the top 10 hottest years for the state.

“No, we haven’t been as hot the last few years as the late 2000 teens, but our time is coming!” warned Rick Thoman, climate specialist at the UAF Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy and editor of the report. “There is nothing in a warming Arctic that says that Alaska is going to be cold again. It’s just year-to-year variability.”

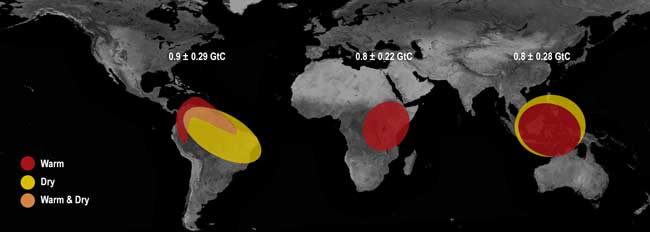

One of the most concerning consequences of this warming is that the Arctic no longer stores more carbon than it releases as greenhouse gases each year. Arctic permafrost holds a vast amount of frozen organic carbon, roughly twice the amount of carbon currently in the atmosphere. In recent years, the Arctic, and Alaska to a lesser extent, shifted from being a net carbon sink to a source.

Recent huge wildfires in Canada and especially Siberia tipped the balance. The fires caused rapid permafrost thawing, accelerating a trend caused by decades of warming air temperatures.

“Though Alaska permafrost thaw is contributing, the big player in the wildfire room is what’s happening in Siberia,” said Thoman. “If next year we have a big big wildfire year, that could change, and Alaska could be the big source.”

This is a global concern as societies struggle to reign in emissions and limit warming.

Warming temperatures are impacting wildlife too. Caribou, an iconic species and critical food source for many Alaskans, are declining due to warmer summer and fall temperatures, changes in winter snow and more human activity. According to the Arctic Report Card, North American migratory tundra caribou numbers have decreased by 65% over the past few decades.

The report focuses on caribou herds above the Arctic Circle, which in Alaska include the Teshekpuk Lake, Central Arctic, Porcupine and Western Arctic herds. Nine other herds in Canada, Greenland and Russia were also included. Recently, the relatively smaller coastal herds like the Teshekpuk Lake and Central Arctic are showing signs of recovery, while the larger inland herds like the Western Arctic are still declining or stable.

In contrast, Alaska’s ice seals are currently healthy. This finding is surprising, given that the sea ice that seals rely on for resting, pupping, pup rearing and molting is declining.

A spotted seal mother and pup rest on an ice floe in the Bering Sea.

The four species of ice seals found in the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas — ringed, bearded, spotted and ribbon — have been sampled during the annual subsistence harvest since the 1960s. Based on this monitoring, there has been no long-term negative impacts to body condition, age of maturity, pregnancy rates or pup survival past weaning.

The report highlighted another difference between Alaska and the rest of the Arctic. While much of the Arctic was relatively dry in 2024, Alaska’s weather was the fourth wettest since 1950. The western portion of the state was particularly wet, which made vegetation more productive or “green” and reversed a “browning” trend that had been occurring over the past five years.

“The west coast was not as brown as some years,” explained Thoman. “Presumably that is reflecting the rainy weather, which shrubs like.”

Similarly, specific Arctic locations may be warmer or colder than normal from year to year, even while the region as a whole is consistently warming.

UAF scientists who contributed to the 2024 Arctic Report Card include: Thoman, editor of the entire report and co-author of surface air temperature section; Tom Ballinger, surface air temperature and precipitation sections; John Walsh, surface air temperature; Uma Bhatt, surface air temperature and tundra greenness; Rick Lader, precipitation; Donald Walker and Chris Waigl, tundra greenness; Vladimir Romanovsky and Eugénie Euskirchen, Arctic terrestrial carbon cycling; and Raphaela Stimmelmayr, ice seals of Alaska.

[content id=”79272″]