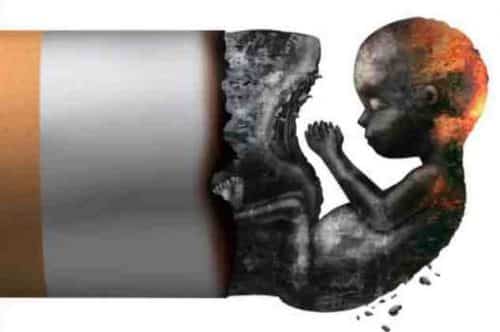

A new study from Sweden reveals that having low peer status in adolescence is a strong risk factor for regular and heavy smoking in adulthood. Researchers from Stockholm University in Sweden used a large database that followed the lives of more than 15,000 Swedes, mainly from the Stockholm area, from birth to middle age.

The researchers isolated 2,329 people who were interviewed once at age 13 about peer status at school and again at age 32 about their smoking habits. The results indicate that the lower a young person’s status is among his or her school peers, the more likely that person is to become a regular (less than 20 cigarettes per day) or heavy (20+ cigarettes) smoker in adulthood.

Unlike some previous studies of peer status and health-related behaviours, this study benefited from an objective measure of peer status, in that the students were not asked to assess their own status but instead nominated the three classmates they ‘best liked to work with at school’. By checking the responses of all classmates from each school, the researchers identified individuals nominated 0 times by their classmates (marginalised students), 1 time (peripheral), 2-3 times (accepted), 4-6 times (popular), and 7+ times (class favourites). Students with few nominations were assumed to be less accepted and respected within the group and to have fewer friends.

|

|

There are several possible reasons why low status children grow up to become smokers. Marginalized adolescents may come to believe in their low status, which may then affect future prospects and ambitions and influence their choices (e.g. smoking) over the course of a lifetime. Marginalized people may be more likely to adopt controversial behaviours, such as smoking, while ‘favourites’ conform to social expectations of good behaviour. Unaccepted youngsters may take up smoking in school as a bid for attention or popularity, with the smoking habit – via nicotine addiction — continuing into adulthood.

What is clear, however, is that anti-smoking programs in schools are likely to be more effective if they increase integration and foster acceptance among students as well as transmitting negative attitudes towards smoking. Not only would adolescent smoking rates be reduced, but the benefits gained from integrating marginalised students could have wide-ranging positive influences on health and health behaviours into adulthood.

Source: Wiley-Blackwell