Ocean temperatures in the Bering Strait and heat transport through the region have increased over the past 20 years. New modeling using a range of temperatures shows that reduced regional September sea ice occurs one to three months after a heat increase.

That’s the preliminary finding of research by University of Alaska Fairbanks doctoral student CeCe Borries-Strigle, who presented her work Thursday at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco.

The research is associated with phase two of the Sea Ice Prediction Network project, funded by the National Science Foundation. The aim is to improve Arctic sea ice forecasts.

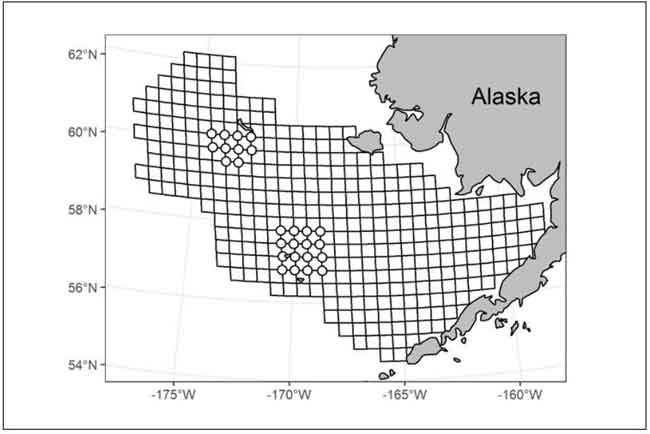

The research could lead to improved predictability of Bering Strait sea ice extent. The strait links the Pacific and Arctic oceans between Russia and the Seward Peninsula on Alaska’s west coast. The strait is about 50 miles wide at its narrowest point.

“This is a theoretical approach to looking at the seasonal predictability of Arctic Sea ice in September, when the minimum extent usually occurs,” Borries-Strigle said. “Knowing the amount of ocean heat that’s coming through the Bering Strait is really important. It’s the only place where water from the Pacific Ocean enters the Arctic Ocean.”

Sea ice forecasting is important for several reasons, particularly for Indigenous communities, Borries-Strigle said.

“They use the sea ice to travel on,” she said. “And they use it as hunting grounds for seals, for example.”

Sea ice also helps protect coastal communities from winter storms. Less sea ice means strong ocean waves can reach the coast.

“As the sea ice has melted and retreated northward, areas have been open to high winds and heavy waves that are eroding the land and forcing villages to consider relocating because buildings are falling into the ocean,” she said.

Having improved sea ice predictions is also important for ships, which are increasingly traveling in the region due to the reduced sea ice.

Borries-Strigle obtained her bachelor’s degree in physics from the University of Illinois and then came to UAF for her master’s degree in 2011.

What drew her to the subject of atmospheric science?

“It was actually just an introductory class that I took in college as part of general education,” she said. “And growing up in the Midwest, the weather is something that we talk about a lot growing up in a rural area with a lot of farmers.”

“I grew up having the the radio on all the time, and it would tell us the daily weather, which is really important for planting and for harvesting,” she said. “It’s something that was always on in the background, and then I was really involved in Future Farmers of America in high school.”

With graduation with a Ph.D. just months away, Borries-Strigle will still be at UAF — as a postdoctoral researcher focusing on seasonal forecasting.

“My Ph.D. has been about seasonal forecasting in Alaska and the Arctic, so I’ll continue to do that with a postdoc position.”

[content id=”79272″]