Washington, DC— A small group of volcanic islands in Alaska’s Aleutian chain could actually be part of a single, previously unrecognized giant volcano in the same category as Yellowstone, according to work from a research team, including Carnegie’s Diana Roman, Lara Wagner, Hélène Le Mével, and Daniel Portner, as well as recently departed postdoc Helen Janiszewski (now at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa), who will present their findings at the American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting next week.

The Islands of the Four Mountains in the central Aleutians is a tight group of six volcanos: Carlisle, Cleveland, Herbert, Kagamil, Tana and Uliaga. They are all what scientists call stratovolcanoes—steep conical mountains with a banner of clouds and ash waving at the summit, probably what most people would sketch if asked to draw a volcano.

Stratovolcanoes can experience powerful eruptions, such as that of Mount St. Helens in 1980. However, these events are dwarfed by the much rarer phenomenon of a caldera-forming eruption, which has potentially global consequences.

A caldera is created by tapping of a huge reservoir of molten rock, magma, in the Earth’s crust. When the reservoir’s pressure exceeds the strength of the crust, gigantic amounts of lava and ash are released in a catastrophic explosion.

Researchers from a variety of institutions and disciplines have been studying Mount Cleveland—the most active of the Islands of the Four Mountains and one of the most active volcanoes in the entire Aleutian chain—to understand the group’s nature. They have gathered multiple pieces of evidence indicating that the islands could, in fact, belong to a single interconnected caldera.

Caldera-forming eruptions are the most explosive type of volcanic events on Earth and their effects are often felt worldwide. The ash and gas they put into the atmosphere can alter Earth’s climate, and trigger social upheaval.

For example, the eruption of nearby Okmok volcano in the year BCE 43 has been recently implicated in disruption of the Roman Republic. The proposed caldera underlying the Islands of the Four Mountains would be even larger than Okmok. If confirmed, it would become the first known caldera in the Aleutians that is hidden underwater.

“We’ve been scraping under the couch cushions for data,” said Roman, referring to the difficulty studying such a remote place. “But everything we look at lines up with a caldera in this region.”

[content id=”79272″]

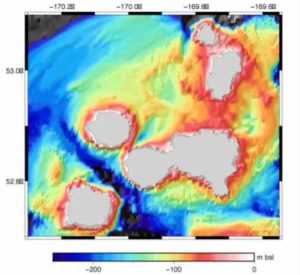

Researchers with different expertise have been gathering evidence using a variety of techniques, including unexpected rock deposits, gas signatures, and gravitational anomalies in the seafloor.

Despite all these signs, Roman along with John Power, a researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey at the Alaska Volcano Observatory and the study’s lead author, maintain that the existence of the caldera is not by any means proven. The study team will need to return to the islands and gather more direct evidence to fully test their hypothesis.

“Our hope is to return to the Islands of Four Mountains and look more closely at the seafloor, study the volcanic rocks in greater detail, collect more seismic and gravity data, and sample many more of the geothermal areas” said Roman.

The caldera hypothesis might also help explain the frequent explosive activity seen at Mount Cleveland, Roman said. Mount Cleveland is arguably the most active volcano in the North America for at least the last 20 years. It has produced ash clouds as high as 15,000 and 30,000 feet above sea level. These eruptions pose hazards to aircraft traveling the busy air routes between North America and Asia.

“It does potentially help us understand what makes Cleveland so active,” Power agreed. “It can also help us understand what type of eruptions to expect in the future and better prepare for their hazards.”

Source: Carnegie Science