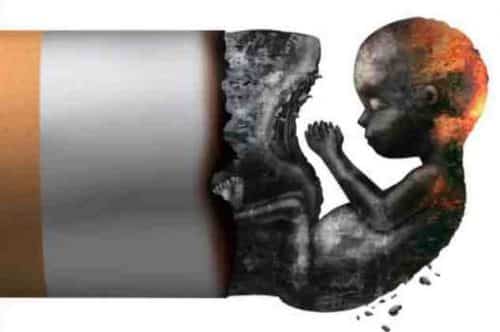

Countless studies demonstrate the virtues of complete smoking cessation, including a lowered risk of disease, increased life expectancy, and an improved quality of life. But health professionals acknowledge that quitting altogether can be a long and difficult road, and only a small percentage succeed.

Every day, doctors are confronted with patients who either cannot or will not quit, says Vicki Myers, a researcher at Tel Aviv University’sSackler Faculty of Medicine. To address this reality, Myers and her fellow researchers, Dr. Yariv Gerber and Prof. Uri Goldbourt of TAU’s School of Public Health, examined survival and life expectancy rates of smokers who reduced their cigarette consumption instead of quitting entirely. Their data covered an unusually long period of over 40 years.

While quitters were found to have the biggest improvement in mortality rates — a 22 percent reduced risk of an early death, compared to smokers who maintained their smoking intensity — reducers also saw significant benefits, with a 15 percent reduced risk. These results show that smoking less is a valid risk reduction strategy, Myers says, adding that formerly heavy smokers had the most to gain from smoking reduction.

This research has been published in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Cutting down for a longer life

To examine the impact of changes in smoking intensity over time, the researchers drew on a sub-cohort of the Israeli Ischemic Heart Disease Study, comprising a database of 4,633 Israeli working males, all smokers at baseline, with a median age of 51 at recruitment. Interviews regarding their smoking habits took place in 1963 and again in 1965, and participants’ mortality status was followed for a period of up to 40 years.

During their first interview, participants were placed in categories by daily cigarette consumption — no cigarettes, 1-10 cigarettes, 11-20 cigarettes, and more than 21. In the second interview, researchers noted whether an individual had increased, maintained, reduced, or ceased smoking during the intervening two years, with “increasing” or “reducing” defined as moving up or down at least one category of cigarette consumption within this range.

Unsurprisingly, quitters were the best-off in the long term, with a 22 percent reduction in overall mortality. Those who reduced their smoking by one category or more were seen to have a 15 percent decrease in overall mortality risk and a 23% reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality. In addition, the researchers measured the participants’ survival to the age of 80. Quitters saw a 33 percent increased chance of survival to 80 years of age, and reducers a 22 percent increased chance.

Myers says that their study, one of the few to take smoking reduction into account, shows that reduction is certainly better than doing nothing at all. She credits the long-term follow-up period for demonstrating the effect of smoking reduction where other studies have not, because damage done by smoking, and subsequently the recovery process, has a long timeline.

|

|

Never too late

One of the important lessons of their study, says Myers, is that it is never too late to tackle your smoking habit. Participants of this study, who were on average fifty years old when the study began, were still able to quit or reduce their smoking, and see long-term benefits from their efforts. Though reduction is a controversial policy — some health professionals believe it dilutes the message of cessation — smokers should take any steps possible to improve their long term health, she counsels.