For the fifth year in a row, Gay Sheffield has been investigating unusual seabird deaths in Western Alaska in collaboration with Bering Strait residents, Kawerak Inc., the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and others. Sheffield is a marine mammal biologist and Alaska Sea Grant’s Marine Advisory Program agent in Nome. Part of her work involves responding to questions and concerns from coastal communities in the Bering Strait region, including reports of marine mammal strandings and deaths.

“The northern Bering Sea has been experiencing seabird die-offs since 2017,” Sheffield explained. “Multiple species of adult birds are washing up on shore, including shearwaters, murres, puffins, gulls, and kittiwakes. This year we’ve also seen cormorants and loons.”

Although seabird die-offs are known to occur sporadically in Alaska, they were rare in the Bering Strait region until 2017, and the increase in frequency, geographic extent, and number of different species involved is bringing more attention to this ecological issue.

In addition to reports of dead birds on local beaches, community members and researchers have noticed fewer eggs and chicks at previously robust breeding colonies.

“The one commonality is the birds are emaciated due to a lack of food,” said Sheffield. U.S. Geological Survey necropsy reports confirm that the bird carcasses have empty stomachs and little or no fat on their bodies. Examination and testing results have confirmed that infectious diseases or harmful algal toxins are not the cause of these seabird die-offs.

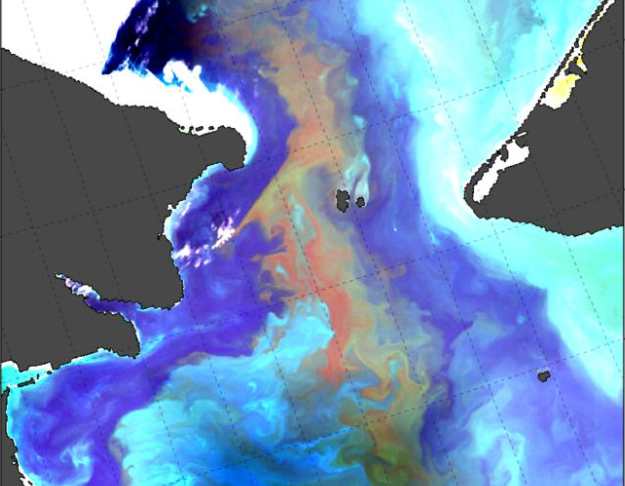

Researchers are still trying to answer why seabirds are starving. Climate change is likely to be a factor. With the ongoing reduction in sea ice quality, extent and duration, the thermal barrier of cold water that separates the northern and southern Bering Sea ecosystems has transitioned northwards, shifting the distribution of large-bodied predatory fish, such as Pacific Cod and Alaska Pollock.

“The large fish may be consuming the small fatty forage fish of the northern Bering Sea ecosystem that the birds had relied on, or perhaps the smaller fishes moved further north to remain in cold water,” explained Sheffield. “Either way, it seems that the birds are not able to find the prey they need to survive.” Researchers have posited that the smaller forage fish might be migrating north to cooler waters earlier than in the past, meaning that breeding birds arriving at the usual spring migration might be finding less abundant prey.

Sheffield explained another possible way the recent reduction in sea ice may be a factor in the food equation. Sea ice acts very much like a greenhouse window, allowing algae to grow on the underside of the ice all winter and spring. With less sea ice, there could be fewer algae to feed zooplankton, and fewer zooplankton to feed the smaller fishes, which stresses the entire food chain.

It’s not just the birds that are hungry. Many seabird species and their eggs are harvested by coastal residents for subsistence, an important source of nutrition for the seasonal summer months. Thus seabird die-offs are an indicator of the health of Alaska’s ocean ecosystems, and also a serious food security concern for coastal residents throughout the Bering Strait region.

Source: Alaska Sea Grant