Next month, Nebraska’s state liquor commission will decide the fate of the tiny but notorious town of Whiteclay, population 12, whose livelihood depends on selling beer—more than 12,000 cans a day, mostly to vulnerable Lakota natives from the nearby Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, which sits only about 60 meters away, over the border in South Dakota.

Marsha and Bruce Bonfleur have operated Lakota Hope, a Christian service ministry in both Whiteclay and Pine Ridge for more than a dozen years.

“During that period we witnessed a lot in the way of human suffering,” said Bruce Bonfluer in an email. “On any given day in good weather, there probably averaged 25 to 30 Lakota men and women struggling with alcohol and life on the street.” On some days, he said, the numbers would double.

“Every day in Whiteclay, there are dozens and dozens of alcohol-consumption violations; people passed out, fighting, etc.,” he continued. And because there are no public restrooms in the town, people urinate, or worse, in the open street or behind trees.

“Public health is a huge concern, always,” he said, “and law enforcement is woefully inadequate.”

For at least two decades, activists have been asking for the state of Nebraska to shut the stores down, resorting to blockades, marches and lawsuits. They blame Whiteclay, which has been dubbed the “skid row of the Plains,” for fueling rampant alcoholism on the reservation.

As many as 80 percent of Pine Ridge residents suffer from alcoholism, which is associated with dozens of chronic diseases, including diabetes, cirrhosis, hepatitis and high blood pressure. Alcoholism increases the likelihood of domestic violence, child neglect and sexual abuse, and accounts for a high rate of suicides, particularly among Pine Ridge youth. Women who drink during pregnancy run a serious risk of damaging their fetuses: To wit, one in every four reservation babies is born with fetal alcohol syndrome or a related disorder. If you are a man on Pine Ridge, chances are you won’t live past 48. Women are a little luckier, with an average life expectancy of 52.[xyz-ihs snippet=”Adsense-responsive”]Since the 1990s, tribal officials and activists have tried everything from protests to blockades to lawsuits in an attempt to shut down Whiteclay’s liquor stores.

Last November, after the beating death of a 50-year-old Lakota woman in Whiteclay, the state of Nebraska finally took notice. Its liquor control commission ordered Whiteclay’s four stores to reapply for their licenses to sell alcohol. If they want to keep operating past April 30, the date their current licenses expire, they will have to demonstrate at an April 6 hearing that they can provide adequate law enforcement in the town. They’ll also have to answer complaints that they break the law themselves by selling to under-age drinkers and intoxicated individuals.

Separately, Nebraska Senators this week gave first-round approval to a bill that would set up a legislative task force made up of lawmakers, public health officials and the state Commission on Indian Affairs to examine what one lawmaker called a “public health emergency” in Whiteclay.

The core problem

But some say shutting down the liquor stores isn’t the answer — among them is Leon Blunt Horn Matthews, a Lakota author, columnist and pastor who has experienced first-hand the despair of Whiteclay.

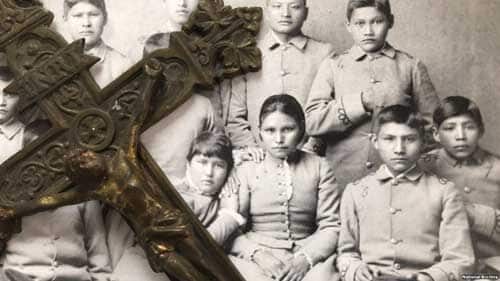

“There are core issues that we need to confront, like the historical trauma they’ve suffered,” he said, citing Native Americans’ history of oppression and displacement.

“People are grieving for their mothers, for their grandmothers, for their children, for their parents. That pain is almost too much. And alcohol just blunts the pain,” Matthews said.

Tim Giago, an Oglala Lakota newspaper publisher and author, takes a pragmatic view.

“We put them out of business and what are we going to end up with?” he asked. “You are going to end up with a Whiteclay with no liquor stores.”

Addicts always find a way, he said, rattling off the names of several nearby towns with ample numbers of liquor stores.

“You can tear down or buy every bar within a 100 mile radius, if you want to. We’ve got bootleggers on the reservation who would take up the slack.”

Giago says the only solution is to address the core problem—addiction—and build a “big, beautiful, state-of-the-art addiction treatment and rehabilitation center.”

As it stands, the reservation’s addicts have few treatment options. The Indian Health Service (IHS), an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is responsible for providing federal health services to American Indians and Alaska Natives. IHS funds and oversees a small, 45-bed hospital in the town of Pine Ridge and five small clinics or “health stations” in other towns on the reservation.

Anpetu Luta Otipi—“Living in a Red Day”—is a small alcohol and drug treatment center about an hour away in the town of Kyle. Tribally-run and federally-funded, it provides 30-day inpatient treatment adapted to fit traditional Lakota culture and values, offering equine therapy, meditation and traditional sweat lodges. However, it can accommodate no more than 10 inpatients at a time.

As it turns out, the Bonfleurs are hoping to address the shortage in treatment options. They say they have met several times with the current beer store owners, who are willing to sell if their licenses are denied.

The Bonfluers recently formed Whiteclay Redevelopment, a low-profit corporation seeking to raise more than $6 million to buy out the liquor businesses and create an entirely new economy in Whiteclay “that respects and honors the Lakota Nation and provides much-needed jobs, hope and a future for residents on both sides of the border.”

Their plan also includes an alcohol detox and rehabilitation facility, possibly in Whiteclay itself.

Bruce Bonfluer acknowledges it is an ambitious plan, and time is running out.

“So, will we raise $6 million?” he asks. “We don’t know yet, but we do know that if the people and the leaders of this great state of Nebraska really believe in a ‘Good Life’ [the state’s longtime slogan], then the money will come in, whether it be through individuals, foundations/philanthropists, government or fundraising on social media or elsewhere.”

Source: VOA