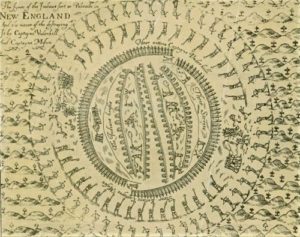

WASHINGTON – Sometime before dawn on May 27, 1637, English militia from Massachusetts and Connecticut, backed by several hundred Narragansett and Mohegan allies, launched a surprise attack on the fortified Pequot village of Mystic, one of about 20 Pequot tribal villages in southeastern Connecticut.

By now, Plymouth Colony, established by the Pilgrims in 1620, was a self-sufficient settlement. After a rocky first winter that saw half the colonists die, the Pilgrims and local Wampanoag tribe signed a peace deal that still held 16 years later.

But things were not so quiet to the west: thousands more Puritans had come to New England and fanned out across Massachusetts and beyond. As each new town filled to capacity, newcomers looked inland to the Connecticut River Valley, which was controlled by the powerful Pequot tribe.

Tensions escalated into a series of attacks and counterattacks. In April 1637, the Pequot raided the English village of Wethersfield, killing nine settlers and kidnapping two young girls who were later ransomed. A month later, the English launched “a full-scale…war of extermination,” as Laurence M. Hauptman, a historian at State University of New York at New Paltz, described it in “The Pequots in Southern New England.”

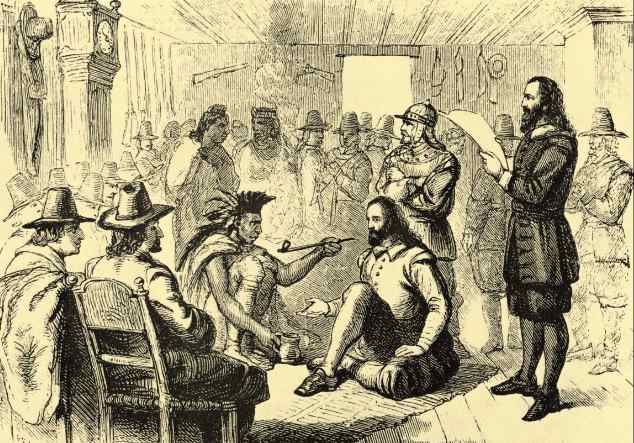

Connecticut militia leader John Mason recorded the details, which were later published as “A Brief History of the Pequot War.”

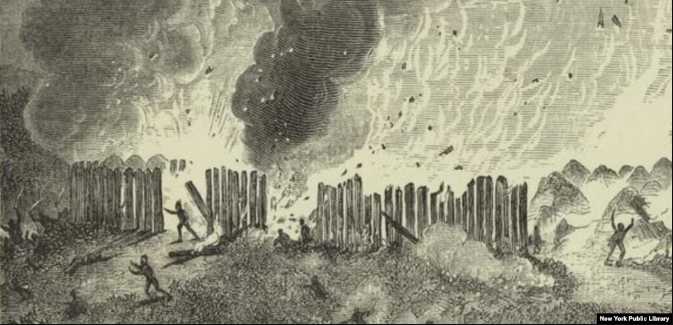

When sword- and gunfighting inside the village proved challenging, Mason and Massachusetts Capt. John Underhill decided to set Mystic on fire. At least 300-400 Pequot men, women and children were burned alive.

“Thus, the Lord was pleased to smite our Enemies in the hinder Parts and to give us their Land for an Inheritance,” Mason wrote, reflecting the European belief in a Divine right to the land.

In the following months, the English dissolved the Pequot Nation and banned the tribe’s name. They turned some surviving Pequot over to the Narragansetts and Mohegans as spoils of war. Others, they sold into foreign slavery in Bermuda and the West Indies.

The Pequot War was the first big conflict between colonizers and tribes in New England. Hauptman said the war established English domination over the Pequot and permanently ruled out any chances of living peacefully together. Today, some scholars—Hauptman among them—say the English committed genocide.

[content id=”79272″]

Linking colonialism and genocide, Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term “genocide” in 1943 to explain mass atrocities throughout history that he believed often occurred as part of colonial conquest. In 1948, the United Nations adopted his definition into the Convention on Genocide, criminalizing acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, and calling for punishment of any persons attempting, committing, inciting or conspiring to commit genocide—regardless of whether they are rulers, public officials or private citizens.

Lemkin’s work is usually associated with the European Holocaust of European Jews, but University of Oregon history professor Jeffrey Ostler told VOA that Lemkin did not limit his studies to Europe.

“Lemkin planned to publish a book on genocide around the world in many different areas, including the genocide of indigenous peoples,” Ostler said. “And he did finish book chapters on the genocide of the Aztecs at the hands of Spanish conquistadors.”

Lemkin died suddenly in 1959 at the age of 59.

[content id=”79272″]

Genocide or ethnic cleansing?

University of Oklahoma history professor Gary C. Anderson says what happened at Mystic—and in later conflicts between the U.S. government and Native Americans—does not qualify as genocide.

“There’s no evidence of any governmental authority—colonial, state or federal—sitting down and putting together a final solution for getting rid of the American Indian,” he told VOA.

“Second, more Indian allies fought with the English against the Pequot than there were Englishmen,” he said. “Genocide calls for the extermination of all people of a certain unique religion or ethnicity. This was the destruction of one village connected to that tribe.”

At most, Anderson said, the incident could amount to ethnic cleansing, a policy of using violence or terrorism to remove an ethnic or religious group from a certain geographic area, which is not a crime under international law.

George Tinker, a professor of American Indian cultures and religious traditions at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado, and a member of the Osage Nation, rejects Anderson’s argument, which he says views Indians as a monolith, not separate nations.

“That’s to lump all Indians together and say, ‘Once you’ve seen one Indian, you’ve seen them all,’” Tinker said. “Genocide against American Indians starts as genocide against each separate Indian nation. The Indians that were with the Puritans as allies were Narragansetts. The genocide was committed against the Pequot.”

He said the fact that some Pequot survived and made their way into other Indian communities doesn’t change the intent of the attack or make it any less genocidal.

After Mystic

The surviving Pequots were not willing to accept erasure as a political entity. In an essay in Hauptman’s book, Jack Campisi, former associate professor of anthropology at Wellesley College, writes that by the 1650s, Pequot prisoners won their freedom from the Narragansetts and Mohegans. They divided into two groups:

The Western Pequots left the Mohegans, and in the mid-1660s, the colony restored to them nearly 1,000 acres at Mashantucket. In 1983, the Ronald Reagan administration recognized them officially.

The Eastern Pequots who escaped the Narragansetts were allotted to a reservation on Lantern Hill in North Stonington, Connecticut, which today amounts to 224 acres. The U.S. government recognized the Eastern Pequots and another tribe, the Pawcatuck Eastern Pequot, as a single tribal entity in 2002. However, the U.S. revoked that recognition in 2005, and a decade later, issued new rules that say a tribe cannot re-petition for recognition once it has been denied them.

[content id=”52927″]

[content id=”79272″]