From Francis Scott Key’s pen in 1814 through war, peace and even Jimi Hendrix’s screeching electric guitar at Woodstock, the Star Spangled Banner has lasted as an American icon — and an anthem that’s nearly impossible to sing.

But as Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information Schooldiscovered when studying Key’s rockets’-red-glare-lit inspiration for his Documents that Changed the World podcast series, the song spread quickly — almost virally — at first, then much more slowly, finally achieving national anthem status only in 1931.

In the podcasts, Janes explores the origin and often evolving meaning of historical documents both famous and less known. UW Today presents these occasionally, and all of the podcasts are available online at the Information Schoolwebsite.

Janes said he chose the topic partly because Sept. 13, 2014, is the 200thanniversary of the night Key scribbled the notes that later became lyrics. But also because, as with others in the series, it was “a familiar story that isn’t entirely, or correctly, known.”

Key was, Janes said in the podcast, “a lawyer, slaveholder, and occasional poet” who really did witness and become inspired by the bombardment of Fort McHenry in the Baltimore Harbor on that September night.

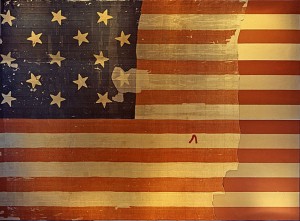

And though a small American flag flew during the battle itself, Janes said, the flag later raised to show victory sounds lyric-worthy indeed.

“Through the rain and smoke of the long day and night of Sept. 13, (Key) has no way of knowing what had happened until the following morning when he is able, finally, to see an enormous flag, raised to the tune of ‘Yankee Doodle,’ sewn by Mary Pickersgill and her family; 30 by 42 feet, three stories high, weighing 80 pounds, containing 350,000 hand-sewn stitches.” (Oh say, can’t you just see it?)

Key’s verses were quickly printed up and circulated as a handbill by one Joseph Nicholson, who was a judge, former Congressman and Key’s own brother-in-law, Janes said.

“Given the circumstances, it’s no surprise that it spread through the city within an hour, ‘like a prairie fire,’ according to one account,” he said.

The song took more than a century to be officially designated as the national anthem and even today there is no “official” version. And as Janes said, “is still is still open to new interpretations, musically and otherwise, even today.”

Janes concludes by imagining how a 2014 Francis Scott Key might react to the stunning, patriotic early-morning vision over Fort McHenry — with, perhaps, a little help from social media.

“Whether by handbill, social media, or just word of mouth,” Janes said in the podcast, “ideas can travel fast, like a rocket.”